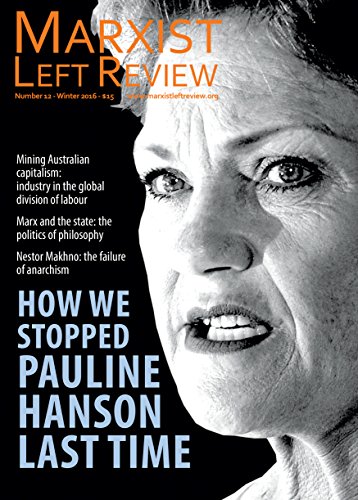

How we stopped Pauline Hanson last time

Playback speed:

In the late 1990s Pauline Hanson was a dominant presence on the Australian political landscape. She polarised Australian society, arousing extraordinarily passionate support and opposition. Elected in 1996, she enjoyed a period of spectacular success, most notably when her One Nation party won a swag of seats in the 1998 Queensland state elections. But Hanson failed to win a seat in the 1998 federal election, and One Nation managed to win only one Senate seat. By late 1999, all of the Queensland One Nation MPs had defected, and support for One Nation had slumped from a high of 22 percent to 5 percent. And by 2002 Hanson had split with One Nation (or been expelled, depending whom you believe) and was largely discredited.

Since 9/11 and the subsequent “war on terror”, the dominant form of racism in Australia, as elsewhere, has been Islamophobia.2 The demonisation of all Muslims as actual or potential terrorists has legitimised discrimination against them; and there has been a deliberate and cynical campaign to conflate asylum seekers, many of whom are Muslims, with terrorists. So in her latest attempt at a political comeback, Hanson jumped on the bandwagon, standing for the Senate on a platform of “absolute opposition to any more Mosques, Sharia Law, Halal Certification & Muslim Refugees”.3 The election result is unknown at the time of writing; but even if elected, Hanson is unlikely to spearhead a racist movement like she did as the leader of One Nation. Back then, Hanson was stopped, in large part by a determined anti-racist campaign. Since then the relentless promotion of Islamophobia, from the very top of society, has fuelled anti-immigrant and anti-refugee sentiment and created a climate that has encouraged the growth of far right racist and even fascist organisations. For that reason, it’s worth revisiting the Hanson experience.

In the months following Hanson’s maiden speech to parliament on 10 September 1996, there was a spike in physical and verbal attacks on members of Indigenous and immigrant communities, especially Asians;4 in a two-month period, reports of racist assaults doubled. Hanson’s frequent appearances on TV and talkback radio legitimised the open expression of racist and anti-immigration sentiment, and gave heart to every far right and racist outfit in the country. She was courted and supported by organisations including the Citizens’ Electoral Council, the Australian League of Rights and the openly Nazi National Action group, which was emboldened to open up a shopfront in Melbourne’s northern suburbs in early 1997.5 Fascists tried to group around her, hitching themselves to her rising star, and initially at least, Hanson did nothing to discourage this. (She was famously photographed kissing a Nazi skinhead at one of her meetings.) This, plus the middle class nature of many of her core supporters, meant that there was a serious possibility that Hanson’s right wing and racist populist movement could morph into a genuine fascist organisation. This article will focus on the nature of Hanson’s support base and the role of protest in the demise of her movement, and draw out some lessons for fighting racism and fascism today.

In her maiden speech Hanson reiterated her attack on Aborigines as a “privileged class” (which had led to her disendorsement as the Liberal candidate for Oxley), asserting that “present governments are encouraging separatism in Australia by providing opportunities, land, moneys and facilities available only to Aboriginals”. She went on to denounce multiculturalism and immigration, echoing people like historian Geoffrey Blainey and Liberal leader John Howard with a warning that Australia was being “swamped” by Asians. Immigrants, she claimed, “have their own culture and religion, form ghettos and do not assimilate”; while “mainstream Australians” were subject to “a type of reverse racism…by those who promote political correctness and those who control the various taxpayer-funded ‘industries’ that flourish in our society servicing Aboriginals, multiculturalists and a host of other minority groups”.

Never has a maiden speech had so much coverage. It was printed in full in many newspapers; some, like the Melbourne Herald-Sun, just printed the speech; others such as The Age identified factual errors and critiqued the speech, but still printed it in full. Hanson was thus catapulted to the forefront of Australian politics. The media – even when they editorialised against her views – followed her everywhere, reported every word she uttered and turned her into a major celebrity. It was estimated that during the first few months after her speech, she was mentioned in the media on average about 200 times every day. Although Hanson only really came to prominence after her speech in September, she was one of the five most talked about people in NSW in 1996,6 and this was also the case nationally in 1997, when she came second to Howard, and again in 1998 when she came fourth after Howard, Labor leader Kim Beazley and Victorian Liberal Premier Jeff Kennett.7 As Socialist Alternative magazine noted: “Every time an issue to do with immigration or Aboriginal people comes up, the media will run to her for a racist quote.”8

The speech polarised opinion and was widely criticised. But Howard “could only rejoice that some of the issues to which he wished to direct attention had been aired and that political correctness has been dealt another blow. In the key period of Hanson’s emergence into the public spotlight and the establishment of her political party, Howard did much to lend her movement an air of respectability.”9

Paving the way for Hanson

At this point it is useful to outline the context for Hanson’s meteoric rise. “Hansonism” was no aberration; it developed out of longstanding racist traditions and was promoted by mainstream political forces. After all, the Australian nation was built on racism, starting with genocidal attacks on the Indigenous population; the White Australia policy both reflected and reinforced anti-Asian racism promoted by ruling circles. And well into the twentieth century, Irish and Jewish people were discriminated against in many ways.

Racism in Australia has always been one of the most effective ways for the ruling class to divert attention from their own crimes and the failings of the system they run. It’s also extremely adaptable: witness Hanson’s switch from anti-Asian racism to Islamophobia. When workers are hurting, they can be more open to divisive ideas like racism, more ready to blame scapegoats and accept arguments that “immigrants are taking our jobs” and the like. The ground was prepared for Hanson by those in the corporate boardrooms and governments who carried out the neoliberal attacks of the 1980s and 90s, and their apologists who launched an ideological offensive that put racism at the forefront of Australia politics.

Social researcher Andrew Markus describes 1984 as the year which “marked the turning point in the introduction of racial perspectives in mainstream political debate”,10 citing significant interventions by the historian Geoffrey Blainey, and Hugh Morgan, CEO of Western Mining and one of the most influential capitalists in the country.

In March Blainey made a speech at a meeting of Warrnambool Rotarians, and followed it up with a newspaper article, warning of the “Asianisation” of Australia. His book All for Australia, also published in 1984, “used the terminology of invasion and warfare to describe the impact of Asian immigration”.11 Hanson praised Blainey’s speech in one of her own to the far right Australian Reform Party in October 1996:

I wish to pay tribute to those people who were prepared to take on the priests of political correctness and their political lackeys long before I came on the scene. In 1984 Professor Geoffrey Blainey delivered a speech…in which he made a reasoned call for a debate on the levels of Asian immigration… Others who manned the barricades on the immigration and multiculturalism issues were Bruce Ruxton, Peter Walsh, John Stone and…Graeme Campbell.12

In May 1984, Hugh Morgan made a speech to an Australian Mining Industry seminar in which he denigrated Aboriginal culture with outrageous claims of infanticide and cannibalism. Morgan was a leading spokesman of the concerted campaign against land rights by the mining industry, which intensified following the High Court’s Mabo decision in 1992.13 Pressure from the mining industry led to the Keating government’s Native Title Act of 1993, which extinguished native title rights on pastoral leases and denied Indigenous people’s right to veto mining; and subsequently to the Howard government’s Native Title Amendment Act, which went even further, delivering, as Deputy PM Tim Fischer notoriously crowed, “bucket loads of extinguishment”.

In 1988, as leader of the opposition Liberals, John Howard launched his own attack on Asian immigration. But in this he was out of step with most capitalists, who favoured increased immigration to expand the workforce and feared that such overt racism could threaten investment and trade by offending Asian capitalists. He was dumped from the Liberal leadership in 1989. But when his successor, John Hewson, lost the supposedly “unlosable” 1993 election by advocating a GST, the Liberals turned back to Howard. The Keating Labor government, despite squeaking back in 1993, was deeply unpopular, not only with capitalists and the middle class who normally support the conservative parties, but also with its working class base, ravaged by Labor’s “reforms”. By the late 1980s inflation had grown to around 9 percent; in 1988, household interest rates peaked at 18 percent and by 1996, unemployment was running at 8.8 percent. So it was no surprise when Howard won the March 1996 election, the election that also saw Hanson enter the federal parliament.

Following Howard’s cue, opposition to racism was now widely derided as “political correctness”. Anglican Archbishop Peter Hollingsworth, who as former director of the Brotherhood of St Laurence posed as a champion of the underprivileged, claimed that the election result was “a reaction against the new political correctness”, while Griffith University Professor Ross Fitzgerald declared that there was a deep resentment against a “punitive, inquisitorial movement” that dared to describe Blainey’s anti-Asian views as racist.14

The parliament passed a mealy-mouthed resolution condemning Hanson’s views on immigration and multiculturalism – though significantly it remained silent about her attacks on Aborigines. But Howard stood firm in refusing to condemn her. This was partly because he shared many of her opinions – Tony Abbott said that “[Howard] feels that her supporters…are the kind of people he grew up with”.15 More importantly however, Howard understood that Hanson’s unleashing of racism presented an opportunity to advance his own political agenda. Former Liberal leader John Hewson observed in June 1998 that: “the Liberal Party actually tried to get on the back of [Hanson’s maiden speech],…to ride it to their electoral advantage. And they are still trying to do it.”16

Howard had toned down his anti-Asian racism in deference to business concerns. But Hanson helped create a climate that enabled him to carry out policies in the interests of the ruling class that meshed happily with his own prejudices and which he would have pursued anyway: the attacks on land rights and native title; the abolition of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC); cuts to immigration, especially family reunions; the ramping up of Islamophobia using the pretexts of “border security” and the “war on terror”.

Howard’s attitude to Hanson eventually changed for two reasons. First, he was the target of sustained criticism from sections of the media, the small-l liberal middle class and even some ruling class figures – prominent businesspeople and Liberal politicians like Victorian premier Jeff Kennett – for not taking a stronger stand against Hanson. This was a product of their concern about Australia’s international image. Hanson was receiving a great deal of media attention in Asia, and as with Howard’s anti-Asian comments in 1988, they were worried about the potential damage to Australia’s business interests and ability to play a dominant role in the region.

Second, and probably of greater concern to Howard himself, Hanson began to cohere a movement and set up an organisation, the One Nation party, that posed an electoral threat to the traditional conservative forces.

A Morgan poll published in The Bulletin in November 1996 indicated that a Hanson-led party could command 18 percent of the national vote, win seven seats in a half-Senate election (up to 12 in a double dissolution), and gain the balance of power. The accompanying article17 noted that Hanson was “leaching support from both major parties”, with 66 percent of respondents agreeing with her call to stop immigration, and 51 percent agreeing that Aborigines received funding and opportunities not available to other Australians. However, the author’s dramatic claim that the poll represented “a decisive shift of working-class votes to Hanson” is not borne out by the figures. On the question: “Do you agree with stopping immigration in the short term?”, 72 percent of Liberal-National voters agreed, and 26 percent disagreed. For Labor voters, the respective figures were 58 and 36 percent. On the question: “Do you agree that Aborigines should get no special advantages?”, 57 percent of Liberal-National voters agreed, and 37 percent disagreed. For Labor voters, the respective figures were 43 and 53 percent. Hanson’s views were clearly more popular among conservative voters. Nonetheless commentary about the level and sources of Hanson’s support invariably emphasised support from working class voters, creating a persistent image of the typical Hanson supporter as a blue collar worker. I will return to this point later.

Despite an election promise to maintain immigration levels, immigration minister Philip Ruddock cut the family reunion intake by 10,000. He disingenuously claimed this was due to high unemployment levels, but it was widely seen as a response to Hanson’s growing popularity. It was the first move in reducing the overall size of the intake and a shift towards “reducing the welfare costs of the [immigration] program and increasing its economic focus” (i.e. to benefit business).18 Hanson was jubilant, and claimed credit for forcing the government’s hand.

Buoyed by this success and encouraged by polls and media predictions of wider electoral success, Hanson formed One Nation in April 1997. An opinion poll the following month indicated that the new party was drawing the support of 9-15 percent of voters, mainly at the expense of the Liberal and National Parties. The June 1998 Queensland state election provided an opportunity for One Nation to test the electoral waters in the area where its support was greatest. The result sent shockwaves throughout the political establishment: with nearly 23 percent of the vote, One Nation won 11 out of 89 seats, exceeding all expectations. And it was indeed the conservative parties who suffered the greatest losses.

Who really supported Hanson?

In the foreword to a book of essays on Hanson, Robert Manne commented: “For many ordinary people [Hanson] became a heroine.”19 But who were these “ordinary people”? Hanson’s supporters were routinely characterised as “rednecks”, “ignorant”, “uneducated” and so on – code for the blue collar working class. But when journalist Phillip Adams attended a One Nation meeting, he found a somewhat different audience:

[T]he meeting…seemed all but devoid of the promised rednecks. Many of the people arrived in BMWs and Volvos – clearly comfortable members of the middle class. And we now know that a sizeable flow of donations to Hanson come from Sydney’s north shore, from the enclaves established by wealthy whites fleeing Mandela’s South Africa.20

For the social historian Janet McCalman, “small business-people, the retired and small farmers” – not “the classic Aussie battlers”, like the unemployed, but “the classic Aussie whingers”– were the sort of people drawn to the One Nation cause.21

Murray Goot, professor of politics at Macquarie University, analysed a series of polls and noted that “many of those attracted to One Nation are voters who would otherwise support one or other of the Coalition parties”.22 Manne praises Goot’s “illuminating critique of the Hanson movement’s male, blue collar social roots” – but Goot’s conclusions are actually more nuanced than this. On the one hand, “[t]he party is peculiarly dependent on voters who have no tertiary education; who, at every age level, are men; and who have blue-collar jobs”. But “retired [people] are more likely than those with jobs to support One Nation”. Further, he notes that “the polls, regrettably, offer no insights into the political preferences of small business operators; in the Morgan poll, the only poll that classifies its data by occupation, those running small businesses are grouped under ‘professionals, managers and owners’ or ‘skilled trades’ and lost to view.”23 That is, at least some of those classified as blue collar workers may in fact have been skilled tradespeople running small businesses, i.e. middle class. Goot concludes on a note of caution:

It is tempting to construct an identikit model of the voter whom One Nation attracts – a poorly educated male, over 50, living in rural or regional Australia and dependent on a blue collar job. But the temptation is best resisted. This model might describe the common (modal) One Nation voter – a victim of restructuring, facing a world whose values have moved on. Yet voters who match this model would account for only a fraction of the party’s vote.24 [Emphasis added.]

Mick Armstrong’s detailed, booth by booth analysis of who actually voted for One Nation in the Queensland election further erodes the notion that her support came mainly from the blue collar working class. He found that One Nation’s support was strongest in what had been National Party strongholds in south-east Queensland – polling 43.5 percent of the vote in Barambah, once the electorate of the right wing Premier, Joh Bjelke-Petersen, and over 30 percent in 11 other seats in this area, compared with a state-wide average of 22.7 percent. Moreover:

South-east Queensland has a high concentration of small farmers, and numerous small towns with a large number of small businesses – newsagents, petrol stations, real estate agents, pharmacists, accountants, farm equipment suppliers – but very few large workplaces with concentrations of unionised workers.25

The general pattern was that Labor did better in the bigger towns but One Nation overwhelmed them in the smaller centres. So the core support for One Nation was the “small town middle class, not – as so many commentators repeat ad nauseam – ‘ignorant’ workers.” Actually, very few blue collar workers defected from Labor to Hanson. Overall, 80 percent of the Hanson vote came from conservative parties and 20 percent from Labor. In addition, while its highest votes were in rural areas, One Nation polled better in affluent middle class areas of Brisbane and the Gold Coast than in poorer working class areas. Armstrong concluded: “It was not the ‘enlightened’ middle class that most strongly rejected Hanson, but unionised, traditional Labor-voting urbanised workers.”

This is consistent with the conclusions of Andrew Markus, who studied a number of election results and notes that:

Hanson’s appeal has been strongest in communities distinguished by a number of common characteristics: relatively small numbers of tertiary qualifications, low median family income, high number of children under the age of five, high unemployment, and residence beyond inner urban areas.…Hanson was most popular among those aged between 45 and 64 and among men.… One Nation polled strongly in rural, hinterland and some urban localities, but not in the inner urban areas.”26 [Emphasis added.]

He also cites the historian Henry Reynolds, who “in his description of One Nation’s heartland…has written of rural and provincial communities that are demographically little changed from the 1950s, have had little or no experience of European and Asian immigrants, and in which anti-immigrant feeling and hostility to Aboriginal people festers”.27

With regard to the seat of Blair for which Hanson stood in the federal election of 1998, Markus writes:

One Nation’s primary vote in Blair ranged from a high of 58.65 per cent at the small Maidenwell polling booth to 18.01 per cent in the north Ipswich booth of Karana Downs. Correlation of these booths with census data indicates a marked differentiation for six of the variables: in the booths recording the highest One Nation vote there was a much higher proportion of the population aged 55 and over, without formal qualifications, unemployed, and with family incomes below $300 per week; lower numbers had tertiary educational qualifications and there was a lower workforce participation rate. [Emphasis added.]

…in Maidenwell, where 27 per cent of the population was over the age of 55…unemployment was nearly 20%… This contrasts with Karana Downs…where unemployment was 4.7 per cent.28

No doubt some workers were attracted to Hanson; after all, as Marx and Engels noted, “the ideas of the ruling class are in every epoch the ruling ideas”,29 and Hanson’s racist utterances were not only tolerated but welcomed by the prime minister of the day and influential media figures like Alan Jones. However, Hanson’s working class supporters were predominantly not from the organised (unionised) working class. Rather, they tended to be unemployed and living outside the main urban centres in areas with a high proportion of small business owners who set the tone of the community – hardly typical blue collar workers. The simplistic and inaccurate characterisation of Hanson’s supporters by the liberal media and sections of the commentariat says a lot more about their own class prejudices than it does about the level of racism in the working class.

Opposition to Hanson

Mainstream accounts of Hanson’s demise generally focus on two main factors: Howard’s tactics on the one hand and Hanson’s failings on the other. Howard implemented many of Hanson’s demands – cutting immigration (especially in family reunion and other humanitarian categories); introducing harsh new measures against asylum seekers and refugees such as temporary protection visas; abolishing ATSIC and extinguishing native title; disbanding the Office of Multicultural Affairs, and according to some sources even banning the use of the word multiculturalism within the public service.30 The cover of Socialist Alternative magazine in July 1998 summed it up: “Hanson says it…Howard does it”. And Hanson herself blamed her declining popularity on Howard stealing her policies.

When the Queensland election revealed the extent of One Nation’s electoral threat to the conservative parties, Howard’s previously indulgent attitude hardened. He finally agreed to pleas to put One Nation last on Liberal how-to-vote cards in future elections, which almost certainly contributed to her narrowly failing to win the seat of Blair. He further entrusted his attack dog, Tony Abbott, with the task of destroying One Nation organisationally. In 2002 Abbott succeeded in having Hanson and one of her senior advisers, David Ettridge, arrested and jailed for electoral fraud, although the convictions were later quashed. By then, however, Hanson’s star had well and truly waned.

The other major factor usually cited is the nature of Hanson’s organisation itself: its complete lack of internal democracy, its bitter internal quarrels, splits and defections, a catalogue of political errors partly deriving from the sheer incompetence of Hanson and her chief advisors, and a series of bizarre stunts. Hanson left herself wide open to mockery with her “beyond the grave” video and her book The Truth, which among other fantasies claimed that Aborigines ate their babies and predicted that by 2050 Australia would be ruled by a lesbian cyborg of Chinese-Indian background.

These factors undoubtedly played a part. The role of mass protest in the decline of support for Hanson, however, has been understated if not completely ignored. Indeed, there has been no account that I have been able to find of what was one of the most militant and sustained protest movements of recent times. Yet it was an important factor, playing a crucial role in preventing the growth and organisational consolidation of One Nation.

There was widespread opposition to Hanson from the outset. Many in the business community were alarmed by Hanson’s anti-Asian policies – not because they opposed racism, but because it was bad for business. This became clear when the Business Council of Australia, along with the Council of Social Services, religious leaders – and, disgracefully, the ACTU – issued a joint statement which condemned her stance on Asian immigration but ignored her equally vile racism towards Indigenous people. This was no oversight: anti-Aboriginal racism was the basis of the business community’s campaign against native title. Small-l liberals generally saw Hanson as dangerous. But they too were more concerned about the national interest and Australia’s international image than with the impact of racism on immigrant and Indigenous communities. Like Tony Abbott in more recent times, Hanson was considered to be an embarrassment.

But there was also a groundswell of revulsion and opposition from what Robert Manne might call “ordinary people”. From the moment Hanson made her maiden speech, people started mobilising against her. Everywhere she went she had to run the gauntlet of protesters. In October 1996 a meeting of the far right Australian Reform Party which was to be addressed by Hanson had to be moved from Melbourne University to a secret venue to avoid a protest by students and ethnic groups. The ARP’s leader Ted Drane explained that “police had warned him of huge demonstrations, saying it would get violent and they would need 80 police to control the crowd”.31 On 23 November, in one of a number of protests around the country, 450 rallied in Canberra where Labor MP John Langmore spoke of the increase in racist violence there since Hanson had been elected; while Aboriginal activist Isabel Coe criticised both Howard’s failure to publicly condemn Hanson and his government’s attacks on Indigenous people:

The racist policies that have been put in place since the Coalition Government came to power, including the cuts to ATSIC,…the $400 million that has been taken away from Aboriginal organisations, will see black people dying – it’s already happening.32

In December, some 50,000 people marched through Melbourne, responding to a call by People for Racial Equality, an umbrella organisation including representatives of the Victorian Trades Hall Council, ethnic and community organisations and churches. VTHC secretary Leigh Hubbard said the rally “aimed to take back the initiative and tell the Federal Government that the majority of people supported migration and Aboriginal people”; Wurundjeri elder Margaret Gardiner called on Victorians to “send a message across the nation that there is no room for racism”.33

The Nazi National Action group got the message, describing the rally as a “disaster” and cancelling plans for a rally of their own in Adelaide, which they had hoped would be addressed by Hanson, the following week. But there was no room for complacency, as events in Port Lincoln (SA) around the same time showed. The mayor, Peter Davis, had told a newspaper that interracial sex was creating “mongrels”. When he refused to back away from these comments and reiterated his strident opposition to multiculturalism, nine out of the 10 Port Lincoln councillors resigned in protest. In the ensuing election, five of them lost their seats to Davis’s supporters.

The establishment of One Nation in April 1997 was an important development in two ways. On the one hand it signified that Hanson was no longer just a lone, independent voice as the local member for one electorate; rather she was setting out to build a national party – an organisation with a political machine, branches around the country and candidates. And given that the establishment of One Nation was predicated on her personal popularity, Hanson had to get out and about to a greater extent, making appearances, pressing the flesh, addressing meetings and the like. On the other hand, these activities also provided greater opportunities for the many people around the country who opposed Hanson and her racist views to mobilise and protest. And they did.

The official launch of One Nation at the Ipswich Civic Centre on 11 April was disrupted by more than 100 angry protesters who smashed windows and tried to stop Hanson’s supporters entering the hall. The next day an anti-racism rally was held in Sydney’s Hyde Park, at which the Racial Discrimination commissioner Zita Antonios warned of the danger of “organised racism” that One Nation represented.34

In Geelong, shopkeeper and Liberal Party defector turned Hanson supporter Andrew Carne advertised a meeting on 5 May to set up One Nation’s first Victorian branch at the Geelong West Town Hall. Deakin University’s Geelong Association of Students immediately called a protest rally, deploring “the fact that Geelong will be the first place in Victoria to have a racist political party”.35 The meeting had to be abandoned after hundreds of protesters forced their way into it, threw eggs and drowned out Carne as he attempted to address about 50 Hanson supporters. The previous night, Hanson herself was abused by hundreds of protesters who had gathered outside a One Nation meeting in Perth.

Following the Geelong debacle, The Age ran an editorial urging Howard to condemn Hanson’s policies. It welcomed the fact that other government leaders had finally taken a public stand against Hanson – but only following the launch of One Nation and the publication of polls indicating that Hanson was “eating into the Coalition’s support”; it observed that “their arguments have rested largely on the nation’s self-interest, particularly in terms of trade” and expressed concern that the government “may be concerned more with its own interests than the potential damage to the social fabric of Ms Hanson’s push”. The editorial also addressed the issue of anti-Hanson protests:

Mr Howard’s initial response to Ms Hanson – ignore her and she will fade from view – was a mistake. She is now the leader of a political party in her own right, she addresses well-attended meetings around the nation and her presence triggers angry demonstrations, such as the one in Geelong on Monday night.… This newspaper does not condone violent protest and does not wish Ms Hanson silenced. Her views should be aired and analysed. But such demonstrations are understandable in the light of Mr Howard’s evident reluctance to tackle Ms Hanson’s views head-on: in such a vacuum, demonstrators might feel that there is no other way to get their point across.36

There are a number of misconceptions here. For a start, it would not have made a jot of difference if Howard had condemned Hanson from the outset; people such as Aborigines, migrants, students, workers (often union members), socialists and other anti-racist activists – who made up the overwhelming majority of the protesters – would have demonstrated against Hanson anyway. For most of us, it was self-evident that the government would only criticise Hanson out of self-interest and in the interests of Australian business; and that the government, with the full support of the likes of the Business Council of Australia, was pursuing policies every bit as racist and destructive of the “social fabric” as those Hanson was advocating. And the protests had nothing to do with the suppression of free speech, as the editorial implied. Silencing Hanson would have been impossible anyway given the amount of space The Age and other media outlets gave her. At the most basic level the protests were an expression of hatred of racism and those who promoted it, and of solidarity with those subjected to it.37 Nor did we call for Hanson’s meetings to be shut down by the state; after all, such powers could just as easily be used against the left as the right. The much misinterpreted phrase “shutting Hanson down” as articulated by the left meant mobilising as many people as possible to actively oppose racism, building a mass movement to send the message that racists who took their vile ideas to the streets or otherwise tried to recruit people to them would always be confronted, deterring potential supporters and thus preventing the consolidation of an organised racist movement.

The media and the establishment condemned the demonstrations out of hand, echoing Hanson’s description of protesters as “thugs”, “ratbags” and the like, focusing on (and wildly exaggerating) the violence of participants while ignoring the violence of police towards them. Howard described anti-Hanson protests as “stupid and counter-productive”38 and a raft of Liberal ministers appealed for an end to the protests, with the likes of Peter Costello and Amanda Vanstone arguing that they only increased Hanson’s electoral appeal. But despite – or perhaps because of – all this criticism, the protests continued unabated, drawing in new forces all the while. For example, the mobilisation of high school students – on a scale that had not been seen since the days of the movement against the Vietnam War – was a notable feature of the anti-Hanson movement. Also conspicuous at the protests were Aborigines and Asians – the latter having seldom participated in such activities previously.

The week after the Geelong protest, Hanson went to Tasmania to raise funds and recruit members to One Nation. The organiser of her public meeting in the Hobart City Hall, Chester Somerville, had promised that it

would be “a night to remember for all Tasmanians”. He was right – but not for the reasons he had hoped.… [He] did not have time to introduce the guest of honour before a surge of protesters flooded the hall, drowning out his opening remarks with a deafening chant of “Pauline Hanson has to go”.

Mainly young and many carrying the Aboriginal flag, the protesters harassed those who had come to hear Ms Hanson speak, shouting “shame, shame, shame” as people entered the hall.39

As one young protester triumphantly yelled: “She came, she saw, she fled.” For Aboriginal protester Amanda Watkinson it meant that “finally another voice is being heard”. One Nation’s Launceston meeting saw another angry protest that included dozens of Aborigines. According to opinion polls at the time, Tasmania was Hanson’s second-biggest support base. But by the time of the 1998 federal election, One Nation’s appeal was lowest in Tasmania and Victoria.40

At the end of May, Hanson held the first One Nation meeting in NSW. Significantly, it was in Newcastle, where she hoped to appeal to a community rocked by the announcement that the BHP steelworks would close in 1999. While 1,200 people paid $10 for a ticket to hear Hanson speak, outside the meeting riot police confronted over 2,000 protesters chanting “No White Australia” and “Racist scum, go home”.41

One of the most militant protests took place on 7 July in Dandenong, a multicultural working class outer suburb of Melbourne where One Nation was attempting to set up a branch. Some 200 Hanson supporters were confronted by thousands of angry protesters, mostly local residents outraged by One Nation targeting their community – further refutation of the idea that Hanson’s base was blue collar workers. Under the heading “Violence erupts over One Nation”, The Age reported that: “[i]n some of the wildest scenes yet at a One Nation rally, bottles were thrown and supporters were pelted with rotten eggs and potatoes as mounted police tried to control [the] crowd”. Seven protesters were arrested and faced charges including hindering police, discharging missiles, and assault. The following night there were more arrests as 100 police in riot gear confronted about a thousand demonstrators at a meeting of the Pauline Hanson Support Movement in Canberra. And so it went on.

If anything, the protests intensified after One Nation’s victory in the Queensland elections. In July 1998 Hanson was forced to abandon an appearance in leafy Hawthorn, a middle class suburb of Melbourne, when over 2,000 people blockaded the Town Hall. It was a similar story a few days later in Bendigo, where she was greeted by what was described as one of the biggest protest rallies ever held there. Large numbers of demonstrators also turned out in Echuca, Sale and Swan Hill. Police were becoming increasingly concerned about the level of security required to protect Hanson and her supporters. The Victorian police minister complained of having to mobilise “more police than we would provide at the Melbourne Cricket Ground for a grand final”42 for the Hawthorn demonstration. One Nation’s Victorian convenor Robyn Spencer railed at the police for failing to use hoses, horses and capsicum spray against protesters; but the balance of forces was such that the police found it more expedient on that occasion (though not on others) to advise Hanson to cancel the meeting. Andrew Markus somewhat grudgingly concludes that the protests succeeded in the aims I outlined above. He describes how Hanson’s public meetings were

an invitation to mass protests in major centres of population. Those who came to hear her message were subjected to abuse, in some cases violence, by anti-Hanson demonstrators. The front pages of newspapers were dominated by images of mayhem outside meetings as police fought to maintain order.… While it is next to impossible to evaluate the impact of the demonstrations, it is possible that on balance they damaged One Nation’s cause; that despite the publicity they gained Hanson they succeeded in the long term in undermining support beyond her core constituency. She faced the problem that the agenda, to an important extent, was set by demonstrators and she was required constantly to respond to charges of racism.43

The role of the media

The militancy of the protests was universally condemned by the media. The Murdoch press, as represented by the Melbourne Herald-Sun, responded entirely predictably. “DISGRACEFUL”, blared its front page headline on 8 July 1997 – referring not to One Nation but to the anti-racists. But the supposedly more liberal media were not far behind. On 10 July the Sydney Morning Herald ran a lengthy feature on the anti-racist movement; it listed nine major protests, involving thousands of people, that had taken place in cities all round the country (in every state and the ACT – and even on the Gold Coast) since One Nation’s launch in March. Both the Herald and the Melbourne Age a few days later warned that the protests were being organised and/or “hijacked” by the left, naming a number of socialist organisations and implying that the mass of protesters – whose numbers far exceeded those of the organised left – were simply dupes of what the Age described as “shadowy revolutionaries”.44 However, passive protests of which the media presumably would have approved, such as a thousand-strong silent candlelit vigil in Ballarat, received absolutely no coverage in the daily papers. The media were only interested in events that they could sensationalise and use to demonise the left.

But if the aim of the media was to deter people from attending demonstrations confronting Hanson/One Nation, they failed. In the next few days more militant protests by hundreds of people took place at One Nation events in Werribee (another working class Melbourne suburb) and Geelong, the latter attended by Hanson. On both occasions, as at most anti-Hanson protests, demonstrators far outnumbered Hanson supporters, as did the large numbers of police deployed to protect the racists. Geelong One Nation convenor Andrew Carne attributed the low turnout partly to the fact that “many were put off by the protesters”.45 Clearly, the protests were having an effect. A Morgan poll conducted for the Bulletin magazine over July 9/10 and 16/17 – when the media was full of reports of anti-Hanson protests – showed that support for One Nation had slumped from a high of 13.5 percent in May to 8 percent. An article in the Illawarra Mercury later that month referenced another poll which (in response to an extremely loaded question) revealed that “a surprising one in 10 voters stated that they approved of violent protests” against Hanson.46 As Socialist Alternative argued:

Hanson’s popularity was greatest when she was able to strut about without any visible opposition. Now that it has been established that wherever One Nation meets there are protests, the Hansonites’ support is falling.47

The article went on to explain why this was the case. First, the protests demoralised the racists: “the sight of the Hansonites cowering behind walls of police while thousands of protesters toss flour bombs at them” made them seem pathetic rather than invincible. Second, the demonstrations helped to bolster and consolidate anti-racist sentiment, showing people who didn’t like what Hanson was saying that they weren’t alone and giving them the confidence to speak out against racism. Third, the presence of angry demonstrators at every Hanson/One Nation event made it harder for One Nation to present itself as an acceptable part of the political mainstream and reinforced its image as political fringe dwellers, “extremists who bring trouble wherever they go”, no better than the fascists who tried to organise among them. And finally, the protests made it much more difficult for One Nation to turn passive supporters into active campaigners and build a stable organisation. All this was the result of militant and confrontational demonstrations, rather than passive events like “multicultural festivals” that took place nowhere near any Hanson/One Nation event, attracted far fewer than the protests and received little or no media coverage. So their impact on the political climate, unlike the protests, was negligible.

Another article in the same issue of Socialist Alternative pointed out that the protests had also caused a shift in the media coverage, using the Herald-Sun as an example. Having initially been a cheerleader for Hanson, devoting a front page to her pledge to clean up crime and printing her maiden speech in full, in more recent times it had become much more critical – running front page articles blaming Hanson for job losses and linking her to the Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke. Following a protest in Adelaide, the paper editorialised that we “must awake to the danger she represents to national unity”, and that she had become “a dangerous phenomenon” who was “polarising extremists of the Left and Right and unsettling middle Australia”. Similarly, after the protest in Geelong, the Herald-Sun bewailed the huge costs to the state of protecting Hanson and urged One Nation to rethink plans to hold similar events. The ruling class, including the Herald-Sun’s backers, came to the conclusion that they did not want Hanson to continue polarising society – especially since Howard could be relied on to implement much of her racist agenda anyway. This shift in the media coverage was a tacit admission that the protests were effective. Following the July 1998 protest in Hawthorn, newspaper banners blared: “Mob halts Hanson” and “Protest silences Hanson” – which while clearly directed against anti-racist protesters, were likely to demoralise Hanson supporters and discourage them from attending One Nation events.

Lessons for today

The Hanson experience shows how a racist movement can take off and grow rapidly – in large part because racism is so deeply rooted in Australia’s history. And the targets can change depending on the needs of the moment, as we’ve seen with the shift from anti-Asian racism to Islamophobia. So despite some advances that have made the overt expression of racist sentiment less acceptable today, it is not surprising that a certain level of racism always persists. In an Essential Report poll published on 18 May 2016, a total of 59 percent of respondents agreed that “The level of immigration into Australia over the last ten years has been too high”, while 46 percent agreed that “Multiculturalism has failed and caused social division and religious extremism in Australia”48 – echoing Hanson’s maiden speech in 1996.

In the past year, far right Islamophobic outfits like Reclaim Australia and the openly fascist United Patriots Front (UPF) have mobilised at times quite large numbers on the streets, in campaigns to stop the building of mosques and the like, and represent the most serious racist mobilisation since One Nation was at its height. In the late 1990s, the anti-Hanson protests were key to stopping fascist organisations from using Hanson as a springboard, as many of those attracted to racist ideas baulked at being associated with Nazis. More recently,

[w]hen Reclaim Australia emerged at the beginning of 2015, it showed every sign it had the potential to develop into a broad far right populist movement with organised fascists at its core. It was only the determined actions of anti-fascists and left wing activists that exposed the truth about the leaders of Reclaim Australia and – through militant, determined counter-demonstrations – made it impossible for them to mobilise on a broad basis.49

Small fascist outfits are a constant presence on the political fringes, an inevitable excrescence of capitalist society. The UPF, True Blue Crew and their ilk have not so far achieved anything like the same momentum as Hanson in her heyday – but then Islamophobia is entrenched in society in a way that anti-Asian racism was not. In April 2016 for example, Casey Council endorsed a racist campaign to stop the building of a mosque in Narre Warren in outer Melbourne. Islamophobes are likely to be encouraged and emboldened by this success, and fascists will see it as an opportunity to draw more people into their ranks. They cannot be allowed to do so.

A comment piece in The Age noted that far right fringe parties such as Rise Up Australia, the Australia First Party and the Australian Liberty Alliance, while “successful in spreading their anti-egalitarian, racist and anti-Muslim agenda in the media and in public street rallies, supported by neo-Nazi and other radical movements like the United Patriot Front” are unlikely to enjoy electoral success. However the authors go on to argue that the danger is that these groups “may subtly push the normative boundaries in the public and political discourse around multiculturalism, equality and the place of Islam and Muslims in Australia”; and further noted that their “overtly Islamophobic agenda” is given legitimacy by anti-Muslim comments by mainstream politicians such as Tony Abbott, George Christensen and Cory Bernardi. This contributes to “the mainstreaming of [the] far-right wing agenda…which gradually shifts the public discourse to the political right”.50

In Europe, the far right has grown alarmingly, against a backdrop of economic crisis and austerity. To give just a few examples: in France the National Front’s Marine Le Pen is currently leading in presidential election polls; the Freedom Party of Austria candidate came within a whisker of winning the presidency in May; the neo-Nazi party Jobbik won 20 percent of the vote in Hungary’s last national election. Invariably, racist scapegoating has been at the forefront of their pitch. But it’s important to remember that the real agenda of fascism is to smash the working class and destroy democracy. Racism is a means to this end.

Since January 2016, the Freedom Party of Austria has been attempting to build a large racist movement on the streets. As Rick Kuhn argues, this would be “a step towards normalising the kind of fascist storm troop activity that has been frighteningly frequent in Greece and Hungary. These efforts have, so far, been successfully confronted by larger anti-fascist counter-mobilisations.” So “exposing the Freedom Party for what it is and undermining its respectability vital for Austrian anti-fascists. This includes…peacefully protesting at its events and confronting its followers when they take to the streets.”51

In many countries however, there has been a reluctance to directly challenge racists and fascists when they organise on the streets. This has only allowed them to grow more confident and assume an aura of respectability. And as we have seen, if they are allowed to present themselves as part of the political mainstream, it can lead to electoral success and create the potential for them to actually implement their racist and anti-working class policies.

This is highly relevant for Australia today. In Melbourne in May 2016, an extremely hostile media response followed events in Coburg, a working class and ethnically diverse suburb, home in particular to many Muslims and people of Middle Eastern heritage. When a rally against racism was called for 28 May 2016, the UPF and the True Blue Crew announced their intention to attack it and to march down Sydney Road, the main thoroughfare. UPF leader Blair Cottrell, an open admirer of Adolf Hitler, promised to use “force and terror” against the rally and against the Muslim residents of Coburg. Yet in the face of this explicit threat, the rally organisers insisted that they would not confront the fascists and agreed to police requests not to march on Sydney Road themselves – which would have allowed the fascists to win the day.

Fortunately, a larger group of anti-racist protesters – significantly including over 100 local Muslims – ensured that things turned out otherwise. They marched to the park where 70-80 fascists had congregated, under heavy police protection, and cornered them, making it impossible for them to get out of the park, much less march down Sydney Road. The media focused entirely on the “violence”, arguing that the left were just as bad as the fascists. And it wasn’t just the media, as Corey Oakley noted:

The accusation that the anti-racists were as bad as the fascists was repeated everywhere – from the conservative right to supposed liberals and even some who claim to be on the left.

It is an ignorant, dangerous and despicable smear. Even if you don’t agree with the tactics of anti-fascist demonstrators, the accusation that they are “as bad as the fascists” is simply ludicrous, and at best demonstrates a complete lack of understanding of the real nature of Australia’s nascent fascist movement.52

The real point was that it was an overwhelming victory and a serious setback for the fascists. And that such small numbers of them turned up in the first place was due to the fact that there had been a number of similar protests in Melbourne since Easter 2015. On every occasion they were beaten back by protesters determined not to allow them the freedom of the streets to spread their message of hatred. And on every occasion, the protesters have copped at least as much media condemnation as the fascists. But the confrontational protests have clearly been a barrier to these groups growing and attracting supporters beyond their hard core. As the popular taunt from our side goes: “You’ll always lose in Melbourne!”

Events like the Coburg protest reinforce the lessons of the fight against Hanson. To have allowed Hanson free rein to hold her meetings and build her organisation would have been a serious setback; just as it would have been to allow fascists to march on the streets of Coburg. Hard-core racists and fascists will not be deterred either by peaceful protests in a different location or by “reasoned argument”. Ignoring them, as advocated by one particularly fatuous commentator,53 but also by some on the left, will only encourage and embolden them. Those who are serious about fighting racists and the fascists who ride on their coat-tails have to be prepared to confront those trying to make racist organisations part of the mainstream; and we cannot allow ourselves to be cowed by the media, who will never support a serious campaign that takes it up to the racists, just as they will never support a strike or any kind of protest that is not completely passive.

Furthermore, it is false to counterpose confronting racists on the streets and building a mass movement, as some on the left do. The anti-Hanson protests encompassed large rallies, most notably the 50,000-strong rally in Melbourne in December 1996, as well as smaller actions involving a few thousand, a few hundred or sometimes only a few dozen. The militant nature of the protests at One Nation events, and media condemnation of it, did not deter tens of thousands of people, from diverse backgrounds right across the country, from attending them. On the contrary, the demonstrations continued and grew, only subsiding once it was clear Hanson was finished and One Nation was no longer making serious attempts to organise.

In the Age comment piece cited earlier, the authors conclude:

The fact that radical fringe groups around the United Patriot Front protested in the streets around the country, most recently in Coburg, not against, but in support of government policies of off-shore detention centres should be a wake-up call. It is a stark reminder [that] fringe groups…have the power to gradually shift the political and public discourse…further into a space from where their agenda does not look so extreme anymore.54

The atmosphere created by governments of both stripes, assisted by the media, has enabled the hateful anti-Muslim, anti-refugee, anti-immigrant politics of the far right to gain a hearing in Australia, and that could have dire consequences, as we have seen in Europe. But the transformation of previously marginal fascist groups there into movements with a mass following was not inevitable. As Corey Oakley argued:

If they had been strangled in their infancy they could have been stopped.

The far right needs to be fought, not ignored or capitulated to. That means having a left that is prepared to take on the right on the streets, and which also wages a broader battle against the racist and reactionary politics of the major parties that gives the far right succour.55

Abbott, Tony et al 1998, Two nations: the causes and effects of the rise of the One Nation Party in Australia, Bookman Press.

Betts, Katharine 2003, “Immigration policy under the Howard government”, Australian Journal Of Social Issues, 38, 2 May 2003.

Fieldes, Diane 1995, “Mabo – End of Terra Nullius?”, The Hummer, 2 (4), Winter 1995, Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, http://asslh.org.au/hummer/vol-2-no-4/mabo-end/.

Markus, Andrew 2001, Race. John Howard and the remaking of Australia, Allen & Unwin.

Marx, Karl and Frederick Engels 2010, The German Ideology, International Publishers.

Notes:

1 This article expands on a section of my article “Racism in Australia: who’s to blame?” in Marxist Left Review 4, Winter 2012. Thanks to Sandra Bloodworth and Mick Armstrong for useful comments on the draft.

2 In Australia of course, anti-Indigenous racism is a constant. There is also a long history of liberal Islamophobia predating 9/11: see Vashti Kenway, “The hidden history of Islamophobia”, in Marxist Left Review 9, Summer 2014.

3 Post on Pauline Hanson’s “Please Explain” Facebook page, 6 October 2015.

4 For example, in April 1997, the NSW Race Discrimination Commissioner reported that formal complaints of racism had doubled during the previous year, and that for the first time race outstripped all other areas of complaints. Sydney Morning Herald, 12 April 1997.

5 See Markus 2001, pp116-141 for a discussion of some of these organisations.

6 Sydney Morning Herald, 20 December 1996.

7 Rehame, 1998 Annual Review, cited in Markus 2001, p159.

8 Socialist Alternative 14, January 1997.

9 Markus 2001, p100.

10 Markus 2001, p59.

11 Markus 2001, p65.

12 Cited in Markus 2001, p147. Bruce Ruxton was the head of the Victorian RSL from 1979 to 2002; Peter Walsh was a minister in the Hawke government who argued that immigration policy under Labor was “driven by ethnic lobbying rather than by rational analysis” (Betts 2003, p174); John Stone was the notoriously right wing Secretary of Treasury during the Fraser government and later a National Party Senator for Queensland; Graeme Campbell was the Labor MP for Kalgoorlie until he was expelled for his racist views in 1995.

13 See Fieldes 1995 for an account of this campaign.

14 Cited in Sandra Bloodworth, “Say no to racist bigots”, Socialist Alternative 7, April/May 1996, p3.

15 Cited in Markus 2001, p221.

16 Cited in Markus 2001, p82.

17 Kerry-Anne Walsh, “The Power of One”, The Bulletin, 5 November 1996.

18 Betts 2003, p177.

19 Robert Manne, Foreword, in Abbott et al 1998, p4.

20 Phillip Adams, “Pauline and Prejudice – It’s in the Bag”, in Abbott et al 1998, p23.

21 The Age, 24 June 1998.

22 Murray Goot, “Hanson’s Heartland. Who’s for One Nation and Why”, in Abbott et al 1998, p55.

23 Goot, “Hanson’s Heartland”, pp57, 62.

24 Goot, “Hanson’s Heartland”, p72.

25 Mick Armstrong, “Who really voted for One Nation?”, Socialist Alternative 28, July 1998.

26 Markus 2001, p204. Markus bases his conclusions on analysis of a wealth of data from the Australian Electoral Commission and various State Electoral Commissions. See Appendix 3, pp230-255, especially Tables A3.9 and A3.10.

27 Markus 2001, p205.

28 Markus 2001, p253.

29 Marx and Engels 2010, p65.

30 Betts 2003, p187.

31 The Sunday Age, 13 October 1996.

32 The Canberra Times, 24 November 1996.

33 The Age, 9 December 1996.

34 Sydney Morning Herald, 12 April 1997.

35 The Sunday Age, 4 May 1997.

36 The Age, 7 May 1997.

37 During this period, Socialist Alternative had anti-Hanson and anti-racist petitions on our regular stalls in cities and on campuses where we had a presence. The response was unlike anything experienced before or since: we were swamped by people clamouring to sign, including many Asians. And people didn’t just want to sign petitions; they raged against Hanson and wanted to know about demonstrations and protests where they could express their anger.

38 The Age, 8 May 1997.

39 Sun Herald, 11 May 1997.

40 Markus 2001, p244.

41 Sydney Morning Herald, 31 May, 1997.

42 The Age, 21 July 1998.

43 Markus 2001, pp169-70.

44 Amanda Phelan and Adam Harvey, “Party Poopers”, Sydney Morning Herald, 10 July 1997; Mark Forbes, “Shadowy revolutionaries behind the Hanson violence”, The Sunday Age, 13 July 1997.

45 The Age, 19 July 1997.

46 Illawarra Mercury, 21 July 1977.

47 Jeff Sparrow, “Hanson protests work”, Socialist Alternative 19, August 1997, p3.

49 Corey Oakley, “Outlawing anti-fascism”, Red Flag 73, 13 June 2016.

50 Mario Peucker and Debra Smith, “Take note of insidious tilt to the right”, The Age, 12 June 2016.

51 Rick Kuhn, “Fascism and anti-fascism in Europe”, Red Flag 73, 13 June 2016.

52 Corey Oakley, “Outlawing anti-fascism”, Red Flag 73, 13 June 2016.

53 Darren Gray, “Left kicks own goal in clash”, The Age, 4 June 2016. In an article of about 800 words, just one sentence was critical of the fascists; the rest was a diatribe against the left.

54 Peucker and Smith, The Age, 12 June 12, 2016. This article (by scholars at the Centre for Cultural Diversity of Wellbeing at Victoria University) was in stark contrast to every other article on the subject published by The Age.

55 Oakley, “Outlawing anti-fascism”, Red Flag 73, 13 June 2016.