Australian perceptions of Japan: The history of a racist phobia

Playback speed:

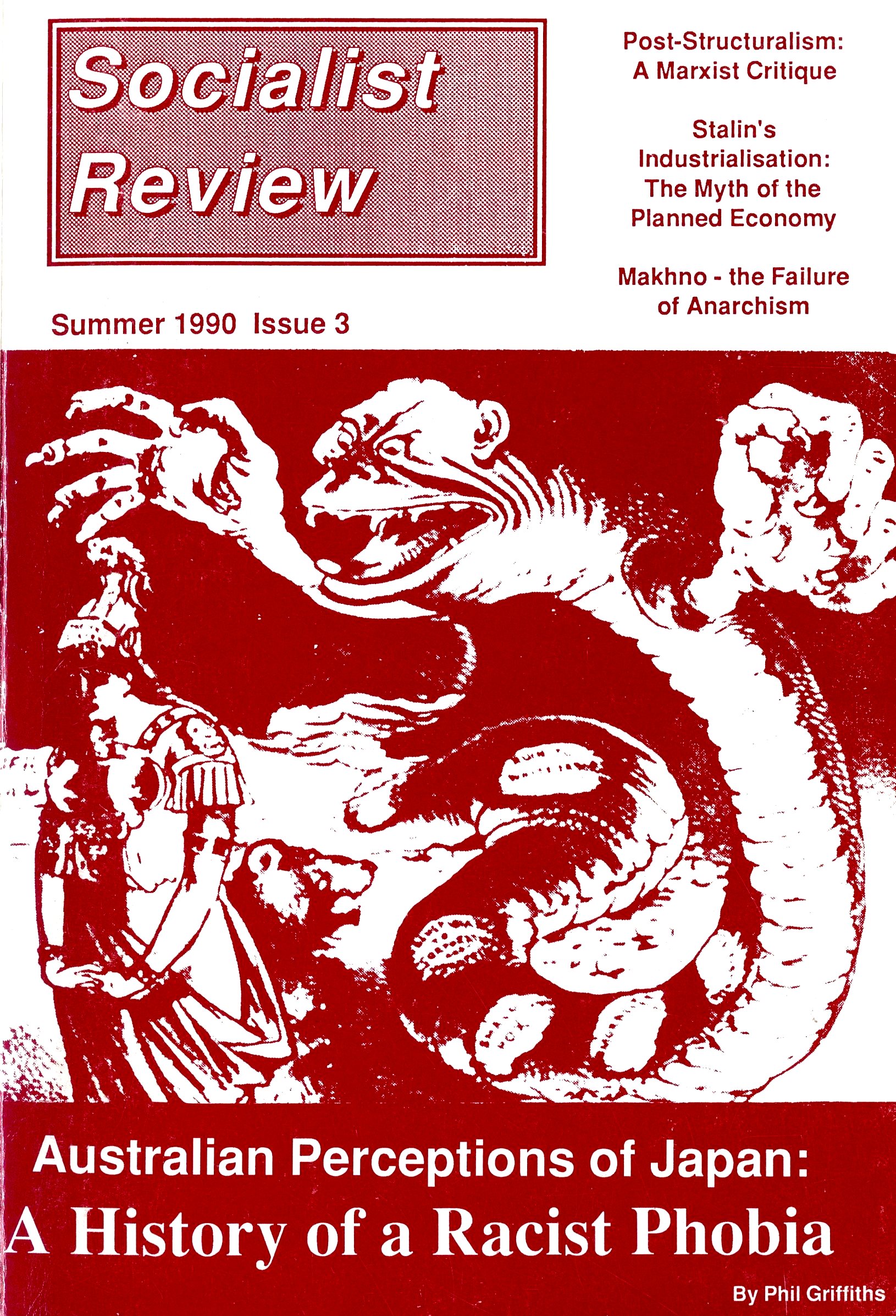

The last two years have seen a rising tide of anti-Japanese racism in Australia. “The Japanese”, we’re told, “are taking over Australia”, and this argument has been buttressed with statistics about the rising level of Japanese investment, especially in real estate. Anti-Japanese campaigns are very popular. Bruce Whiteside has managed to build large meetings on the Gold Coast in protest against Japanese investment there. In Melbourne in March 1990, the Rainbow Alliance organised a public meeting of over 1,000 in the South Melbourne Town Hall to protest against the proposal to build the Multi-Function Polis in Port Melbourne. The poster for the meeting centred around a racist caricature of a Japanese face. Racists such as Australians Against Further Immigration were able to propagandise at the meeting with impunity and members of the audience boasted privately that they had come because the meeting was about “kicking the Japanese out”.[1] When a decision was made to build the MFP near the Gold Coast, a protest rally was quickly organised at which the dominant politics were anti-Japanese, with people wearing T-shirts saying “Slap a Jap”.[2]

Naturally enough, most of the far right actively supports this racist shift – people like Bruce Ruxton from the Victorian RSL have been “warning” us about Japan for decades, and organisations like the ultra-right League of Rights and the fascist National Action find themselves cutting with the grain of popular prejudice. Such was always to be expected from them. The tragedy and danger in the current situation is that so many on the left and in the environment movement have not only fallen in behind the anti-Japanese agitation, but are out in front leading it – promoting images of Australia being “taken over” by the Japanese through books like The Third Wave: Australia and Asian Capitalism and through the campaign against the Multi-Function Polis. People who demonstrated against apartheid and for Land Rights, people who were arrested and vilified for opposing the war in Vietnam, are now, however unintentionally, lining up with the extreme right – people who are for apartheid, who were for “nuking” Vietnam – in promoting anti-Japanese paranoia rather than fighting it and exposing its class collaborationist and imperialist logic.

After all, if we really are all “Australians”, and if “Australia” is threatened by “Japan”, then what’s the logical conclusion? We must all make sacrifices to strengthen “our” industries against Japanese competition (i.e. wage cuts, restructuring, working harder). If we all have to promote the strengthening of “our” industry to compete, then doesn’t that mean that environmental considerations have to take a lower priority? If Japan’s military expenditure continues to rise, it is only common sense that we should beef up “our” military too. In any brawl between Japanese and US capitalism, wouldn’t the argument against US bases in Australia be weakened? And as anti-Japanese feeling rises, does anyone seriously imagine that hundreds of thousands of people of Asian descent feel any safer from racist discrimination and abuse?

When they first presented their anti-Japanese message to Sydney’s leading left forum, Politics in the Pub, Ted Wheelwright and Abe David explicitly linked Asian immigration to the supposed “Japanese threat”, arguing that there was a danger that Asian immigrants would not be loyal to “Australia” but instead act as a “fifth column” to support Japanese attempts to dictate government policies. This article does not set out to reply to Wheelwright and David’s book in any detail, nor to rebut all aspects of the anti-Japanese argument. That has been and will continue to be done elsewhere.[3] My intention is to analyse the reasons for, and history of, anti-Japanese paranoia, rooting it in Australia’s position in the world system as a white colonial settler state in Asia, and of our ruling class as the junior partner of British, and subsequently American, imperialism in the region.

The roots of racism

Marxists have long identified the rise of racism in human society with the emergence of capitalism, and in particular the slave trade. As slavery was abolished and great, new empires constructed, the racist ideas promoted by the ruling class changed; there was a remoulding of the old idea of blacks as “sub-human”. A new “racism of empire” was constructed, typified by the paternalistic notions of Kipling’s White Man’s Burden.[4] As imperialist rivalries and imperialist conquest intensified towards the end of last century, racism was unleashed on a massive scale and buttressed with all kinds of scientific hokum, including the measuring of skulls. As capitalism developed – unevenly – the large-scale migration of labour became a feature of the system and racist ideas were adapted to divide the emerging working class within the imperialist powers. By 1870, Marx was arguing that “the secret of the impotence of the English working class, despite its organisation”, lay in:

a working class divided into two hostile camps, English proletarians and Irish proletarians. The ordinary English worker hates the Irish worker as a competitor who lowers his standards of life. In relation to the Irish worker he feels himself a member of the ruling nation and so turns himself into a tool of the aristocrats and capitalists of his own country against Ireland, thus strengthening their domination over himself.[5]

This second aspect to the “racism of empire” – the racism of immigration – has become the dominant racism in the advanced countries. It was not simply a “ruling class plot” (though the ruling class did consciously promote it); racist ideas in the working class rest on the real material conditions of existence workers face, of being forced to compete with each other to sell their labour power to the capitalists.

There is, however, a further dimension to the “racism of empire” which I call the racism of imperial rivalry. Imperialism was never just a system of colonies, of the domination of the small, weaker countries by the great powers. For both Lenin and Bukharin, imperialism was the “highest stage of capitalism”. It was the system of rivalry between the great powers and the new element it introduced was the central role of the state machine – the armed forces and government – in capitalist competition. The rivalry shifted from being primarily economic to economic and military combined, and at times, the military element would be decisive. This analysis was developed in the heat of the First World War to explain why the great powers had dragged the world into such a barbaric catastrophe.

The development of productive forces moves within the narrow limits of state boundaries while it has already outgrown those limits. Under such conditions there inevitably arises a conflict, which, given the existence of capitalism, is settled through extending the state frontiers in bloody struggles…[6]

In such a situation, the victory of any power rests partly on its ability to “gain power not only over the legs of the soldiers, but also over their minds and hearts”, as one German imperialist put it. In this task, racism is of inestimable value. As Pete Alexander argues:

Race had one further advantage. Where religion tended towards universalism, racism…tended to the particular…it could be used to justify the domination of certain Christian Whites over other Christian Whites. Race could become nation, and nation could become race… [This] was a powerful means of mobilising the masses in times of war.[7]

The racism of imperial rivalry is what lies behind the British calling the Germans “Huns” and “Krauts” – witness the recent racist comments by British Tory Minister, Nicholas Ridley, about German unification (a “fourth Reich”, Kohl like Hitler). Likewise the nature of Australian fears of Japan – historically the fear of invasion; today the fear that Japan is “taking over”, trying to resurrect the Greater East Asian Co-Prosperity Sphere of the early 1940s – are different from traditional working class fears of “cheap labour”. They are fears that reflect the reality of imperialist rivalry, fears that, in an era during which the interpenetration of capital has leapt forward, the independence of the Australian state machine has been compromised (it has) and that Australian nationalism, for so long the ideological cornerstone of the Australian left, is an increasingly meaningless quantity (it is). It is in that context that arguments about Japanese “culture” and “traditions” are made.

Apart from resting on absolute nonsense – at no point did the Japanese government ever have any plans to actually invade Australia – this paranoia also dodges the fact that long before most Japanese even knew where Australia was, Australian society was consumed with anti-Japanese scare campaigns and demands that the government prepare for war with them. Indeed, anti-Japanese paranoia has been a central feature of Australian politics nearly all this century. It first emerged as a substantial force in 1895. By 1908, we had the Prime Minister, Alfred Deakin, inviting the “Great White Fleet” of the US Navy to visit Australia. The Fleet had been sent around the Pacific by President Roosevelt explicitly to intimidate the rising Japanese Navy. In Australia it was everywhere met by huge, adulatory crowds. Deakin explained the popularity of the visit as:

not so much because of our blood affection for the Americans…but because of the distrust of the Yellow Race in the Northern Pacific, and our recognition of the “entente cordiale” spreading among all white races who realize the Yellow Peril to Caucasian creeds and politics.

We should keep in mind that this is not 1939 – it is 1909. At the time, Japan had an economic and military alliance with Britain. Viewing the Australian response to their economic and military development, Japanese politicians would have been entirely justified in arguing that Australia was fundamentally hostile to Japanese interests, that its politicians were trying to draw Britain into conflict with it and that if this continued it would inevitably find itself at war with these white racist fanatics from the south, and that it should begin preparing for this contingency.

A colonial settler state in Asia

To explain this xenophobia, we need to understand the position of Australian capitalism in the world system. Britain “took possession” of Australia in order to expand the Empire, to provide a base in South East Asia – and to keep it from the rival French. In order to secure this new possession, it sent prisoners from its overcrowded jails to settle here. The rise of the wool industry, in tandem with Britain’s burgeoning textile manufacturing, provided the foundations for a dynamic, indigenous capitalist class, with its own distinct interests.

Australian capitalism faced two serious problems. On the one hand, Australia has an enormous coastline, and a few hundreds of thousands of people on its dispersed farms and in its widely spread coastal cities simply would have very few resources to challenge any well-armed invaders. On the other hand, its growth was continuously hampered by a shortage of labour (the Indigenous population having been rejected as unsuitable). For young Australia’s ambitious politicians, one part of the solution lay in extensive economic development which necessitated a forced march to boost the labour force. The strategy was summarised in the slogan “Populate or Perish”. The second part of the solution lay in making sure that British imperialism maintained the strongest possible military presence in the region. The nationalist myth has it that the British were always determined to force Australia to do their bidding. This undoubtedly happened, but the dynamic of the relationship was the other way around – it was the Australian ruling class that continuously attempted to force Britain to tie its imperial interests to Australia’s security.

So it was not enough to raise a labour force from anywhere in the world that people could be found to work. From the very beginning, urban capital in Australia insisted that migrants had to be British, and therefore (with the unavoidable exception of the Irish whom they would also have liked to keep out) loyal subjects of the Empire, who could be counted on to defend British interests and to whom the British would be forced to provide some security. While “White Australia” is usually taken to mean the Immigration Restriction Acts that prevented all non-“white” people migrating to Australia, the policy had an equally important component – the active promotion of British immigration to the colony. As William Morris Hughes was later to put it in his series of articles, The Case for Labor, written in 1909, “the national safety of Australia hangs on the complete and speedy absorption of large numbers of suitable immigrants”.[8]

Thus the White Australia policy did not grow (as is alleged by almost every historian) from the racist demands of the labour movement, but from the needs of Australian capitalism and British imperialism. Indeed, as early as the late 1820s, the squatters attempted to get approval to import Indian and Chinese labourers to mind their sheep. Their attempts were bitterly fought by both bosses and workers in the cities and vetoed by the Colonial Office, which was concerned to prevent the development of a low-paid Asian workforce that would discourage British settlement. The colonisation schemes of Edward Gibbon Wakefield were likewise proposals to extensively populate Australia with workers and displaced farmers from Britain to guarantee loyalty to the Empire. Although he didn’t use the slogan “White Australia”, this represented the first systematic exposition of one side of the policy.

The importance of Humphrey McQueen’s book, A New Britannia, was the recognition that Australian nationalism had always been racist, because in it, the racism of empire was intensified by Australia’s proximity to Asia. McQueen also argued that Australian nationalism had not been anti-imperialist, but a nationalism that complained that Britain was not imperialist enough.[9] Thus it was Australian bosses that demanded that Britain take control of Fiji. In 1884, the Queensland government declared British control over Papua in the hope that this would force London to take it into the Empire and forestall the advance of the rival Germans.

In Australia, a vast continent still insecurely held by the various independent colonies, the growing imperialist rivalries of the 1880s were keenly felt. There was outrage at the British when they “allowed” the French to seize New Caledonia. A series of rusting artillery installations around our capital cities stand as mute testimony to continual fears that the Russians were about to invade. The acceleration of imperialist rivalries also saw an entirely new series of campaigns against Asian immigration – campaigns which led to the complete banning of Chinese immigration under what became known as the “White Australia Policy”. “White Australia” racism thus represented a mixture of arguments, partly depending on which class it was aimed at. To the workers, the danger of “cheap coloured labour” was emphasised and the “need” to increase immigration from Britain (usually unpopular with the working class) was not. From the mid-1880s on, the press was continually in a frenzy about the supposed danger of an “invasion” by “the Chinese hordes”.

During the nineteenth century, the “baseness” and “degeneracy” of Chinese people was a staple argument. But as “White Australia” was institutionalised in the Immigration Restriction Acts, and as Japan grew in stature as a world power, the form of the racism shifted. Indeed, as the twentieth century developed, the emphasis from politicians has been more and more that Australians don’t see Asians as “inferior”, just different, and that their exclusion is the key to a “harmonious” society without racial conflict.

The revolutionary alternative

But while racism has real, material roots, there are material factors even more powerful that can form the basis to challenge it. For a start, the enormous national movements in Asia between the wars and especially afterwards, aroused considerable working class sympathy. The ruling class, desperate to contain “communism”, was also forced to take them seriously and it was this that drove them to gradually shift from the overt racism of “White Australia”. But the need to continually stimulate Australian nationalism, and the centrality of the Pacific War in that, make it impossible for them to seriously challenge racism. But most important of all, the conditions of existence of the working class include large-scale co-operative labour in the factories, mines and offices – conditions which underpin union organisation and ideas of class solidarity – and internationalism. Thus the dominant working class politics, reformism, is contradictory – both accepting the system and pointing beyond it. One result of the contradictory nature of working class consciousness is, as Alexander points out, that “it is possible to be a class fighter and a racist” – and neither consistently.[10] So it is true that most workers strongly supported “White Australia”, but were able to enforce the magnificent union bans against Dutch shipping from 1945 that played such an important role in the struggle for Indonesian independence. We see this phenomenon on the left all the time – people opposed to racism in general accepting, or even making, racist arguments about the Japanese.

The destruction of capitalism, and specifically of labour power as a commodity, are preconditions for the smashing of racism as an ideology. And within capitalism, the working class is the means by which this can happen. But the possibilities of workers’ revolution also hinge on the role played by socialists in the class struggle – and specifically in the struggle against racism and imperialism. Most Australian workers identify with the Australian nation state. That is a powerful weapon on the side of the ruling class – its value can be seen in the ease with which real wages have been cut in Australia through the economic boom of the late 1980s. But today workers are angry. They can lash out against immigrants, or Japanese, but also fight their real enemies, the bosses, and in doing so start to find a real path forward.

Identification with imperialism guaranteed working class support for the invasion of Korea, and support in the early years of Vietnam. In the Second World War, it guaranteed that Australian workers would willingly go out to kill Japanese workers in the interest of American and Australian control of the region. But all these wars also turned many workers in an anti-racist direction, when they saw that the people they were fighting were just ordinary, powerless cogs in the machine, just like them. The struggle against imperialism and racism is a struggle to convince workers to identify with the international working class, and to reject any identification whatsoever with their bosses. This is not simply a matter of being “non-racist”. It means active support for positive discrimination in favour of the oppressed; it means opposition to all immigration controls; it means wishing for the defeat of your own ruling class in any attempt to suppress the national rights of weaker countries, and preferring the defeat of your own side, rather than any co-operation with it, in any inter-imperialist war such as World War II.

In Australia, the questions of Japan, and of Asian immigration, have always been the touchstone of genuine socialist politics. The tragedy of the left is that for most of its history it has been mired in a swamp of Australian nationalism and anti-Asian and anti-Japanese racism.

The emergence of Japanese imperialism

A crucial element in the racist mythology is the way the rise of Japanese imperialism is seen as something different and threatening. In their book, The Third Wave, Wheelwright and David find it ominous that this

is the first time in 500 years of capitalism that the dominant forces are not of European or Anglo-Saxon origin…the political, social and moral traditions of the investing countries are different, and the language and cultural barriers are more difficult to surmount.[11]

This is racist nonsense. In the middle of last century, Japan was still an essentially feudal society. The mass of the population were farmers and the ruling class rested upon its control of the land. Moreover it was a relatively peaceful feudalism; the Tokugawa shogunate had brought the samurai caste, the only caste allowed to bear arms, under central control and turned them into bureaucrats for the central state. While Bushido presented itself as the philosophy of warriors, it was dominated by ideas of self-sacrifice and public service – defined, of course, with the interests of the ruling class. However, within a few decades, everything had changed. By the end of last century, imperialist Japan was very definitely in the making. It had defeated China to gain control of Taiwan and economic and political rights in Korea. Japanese feudalism had been smashed and the economy was rapidly being restructured around modern industry and capitalist relations of production, with a large arms sector leading the way. Japan had had its own bourgeois revolution, but it had been a revolution from above.

The key to this transformation was the expansion and plunder of British and American capitalism. The crisis inside Japan that led to the Meiji restoration of 1868 began in 1854 when the American Commander Perry sailed his fleet into Tokyo and forced the Emperor at gunpoint to allow unrestricted access for American exports. It immediately became clear to the ruling class that it did not have the military strength to prevent the imperialist powers gaining a hold over Japan. What that held in store could be seen by the brutal subjugation of both India and China. It is often forgotten that when Europeans first traded with India, they did not find a backwater, but a country “not inferior to that of the more advanced European nations”. As Peter Fryer put it:

India was not only a great agricultural country but also a great manufacturing country. It had a prosperous textile industry, whose cotton, silk and woollen products were marketed in Europe… It had remarkable and remarkably ancient, skills in iron-working. It had its own shipbuilding industry…and in 1802 skilled Indian workers were building British warships at the Bombay shipyard of Bomenjee and Manseckjee.[12]

The victory of Robert Clive in 1757 began a plunder unprecedented in human history. It is estimated that between 1757 and 1815, Britain’s loot amounted to between 500 million and 1 billion pounds – not in today’s values, but at a time when wages were a few shillings a week. By forcing India to buy British goods, and by using tariffs to keep Indian goods out of the British market, British industry leapt forward and India was de-industrialised, transformed into a state of abject misery. The result was that famines, which had previously been relatively infrequent and localised, became so general that the result was starvation on a mass scale. According to official statistics, 28,825,000 Indians starved to death between 1854 and 1900. One can understand the frenzied concern of the Japanese ruling class to renegotiate the unequal treaties forced on it by the Americans and avoid the fate of India.

But it was the subjugation of neighbouring China that had the greatest impact on the Japanese. One of the most brutal and decisive episodes in China’s defeat was the Opium War of 1839-42. British merchants made enormous profits by exporting opium and all its attendant misery to China. Attempts by the Chinese to ban the trade failed, and when they burned 20,000 chests of opium, it gave the British an excuse to invade. Further invasions by British, French and American forces followed which led to more humiliation for the Chinese. The Treaty of Tientsin, to which Russia, France, the US and Britain were parties, finally legalised the opium trade. This was the “civilisation” that the West brought to China and it was the fate that beckoned Japan when Commodore Perry arrived in 1854. Here is how one samurai reacted to what he saw in Shanghai a few years later in 1862:

Here most of the Chinese have become the servants of foreigners. When English and French people come walking, the Chinese give way to them stealthily. Although the main power here is Chinese, it really is nothing but a colony of England and France… [We] have been forewarned – who can be sure the same fate will not visit our country in the future?[13]

There are many reasons why the Japanese ruling class was almost alone in proving able to rapidly transform their country into a modern, advanced industrial and military power. But the fact is they did not do it of their own choosing. The barbarity, especially of British rule in India and China, gave them a very stark choice – forced industrialisation and militarisation, or abject surrender. The rise of Japanese imperialism gave socialists no cause for joy, but we have to be clear where the blame for it lies. It was precisely the emergence of great powers carving up the world that meant that in weaker states with more backward economies, the only prospect of national defence and economic survival was if the state, and especially the military, played a central role in transforming the economy. Thus the emergence of state capitalism in countries like Germany and Japan (and indeed Australia in a slightly different way) was intimately bound up with the rise of imperialism, and most especially the imperialisms to which Australia has historically been allied – British, and later American. In Japanese politics from that time on, the rise and fall of various political factions within the bureaucracy and the military would be influenced as much by the pressure on Japan from the major imperialist powers as by any internal issue.

Australian reactions to the rise of Japan

Before 1895 Japan had virtually no impact on politics in Australia. To the extent that there were fears of an invasion, they centred on attempts by the major European powers, especially Russia, to expand their empires, and the “Chinese hordes” over-running the country in a desperate desire to relieve the pressures of population. The only time Japanese people were an issue was when small numbers migrated to work, for instance in the pearl-shelling industry. In 1894, Japan went to war with China to consolidate its authority in Korea, which both countries jointly dominated. Japan’s victory brought it to the attention of the world as a rising power, and this was especially true in Australia. Writing on the eve of the Second World War, as tensions in the Far East escalated, the American scholar Jack Shepherd argued:

The outbreak of war in the East in 1894 brought Japan very much into the public eye in Australia, and wrought a complete change in the Australian attitude toward the Japanese people. Hitherto regarded as a completely harmless and rather curious nation…Japan was rapidly elevated…to the rank of a “menace”.[14]

In 1895, colonial military exercises involved repelling an imaginary Japanese naval attack on Sydney Harbour.[15] The “White Australia” legislation that existed in most of the colonies, and which focused on preventing Chinese immigration, was quickly widened to include all Asians. The Sydney Morning Herald spoke of

the presence in the Pacific of a warlike and resourceful Power whose existence is as important to us as though an ambitious European nation had established herself as our near neighbour.[16]

In excluding all Asians, the Australian colonies immediately came up against the wishes of the British government which had signed a Treaty of Commerce and Navigation with Japan in 1894 and which wanted the colonies to join. Since the treaty conferred reciprocal rights of residence, trade and acquisition of land, all the colonies apart from Queensland refused to join – despite the favourable tariff treatment that Australian exports would also enjoy. Indeed, it was the dispute over the treaty that led to the rush to exclude all Asian immigrants, and this, along with the racist terms in which the colonies discussed Japan, created diplomatic problems for the British. Australian foreign policy began with a racist hostile attitude towards Japan. In what is probably the most important and thorough survey of Australian attitudes to Japan between 1894 and 1923, David Sissons warned against exaggerating the degree of hostility towards Japan, or the homogeneity of it. In surveying press opinion, he pointed to “papers which either were unconcerned or vigorously rejected any suggestions that Japan was to be feared”.[17] He also showed that many of the papers that were concerned about Japan admired Japan’s rise, supported its side in the war, and saw it as a buffer against the Russians and a vehicle for opening up the Chinese market. In addition, they did not necessarily draw the conclusion that the colonies needed to boost their military spending. To this effect he quotes The Bulletin, at the time a rampantly populist paper, nationalist in the extreme, with an extensive working class readership – and subsequently to become the leading organ of anti-Japanese hysteria:

The Chinese bogey died about two months ago, and before it was decently interred the Japanese bogey arose in its stead…

Japan is no more dangerous to us than she was a year ago or several years ago. She is little more dangerous than Chili [sic)… Japan is a peaceful and long-suffering state, and about the least likely of all States to go pervading the earth in search of remote and needless enemies. She has no quarrel with Australia and Australia has none with her.[18]

The essential fact remains that in 1895 Japan went from being irrelevant in Australian politics to suddenly become a military-strategic factor. That, as we have seen, doesn’t mean that everyone was suddenly hostile to Japan or immediately thought of war, but it does mean that the ruling class suddenly realised that Australian capitalism now had a powerful potential rival in the region – a region distant from the heartlands of Britain’s military might.

Hysteria becomes the norm

By 1907 hysterical fear of Japan had become hegemonic in Australian politics – dominant both in the ruling class and the wider population. The hysteria was prompted by Japan’s victory over Russia in the war of 1904-5, but bore absolutely no relation to any rational appraisal of the possibility of either a Japanese invasion or Japanese military hostilities directed at Australia. The effect of the hysteria on government strategy was profound. It was largely responsible for the establishment of a separate Australian navy, breaking a long history of purely relying on financial support for the British naval presence in Asia. It swung ruling class support behind those who were arguing for compulsory military training for all young people.

If Japan had designs on Australia, it had a strange way of satisfying them. In 1902, it strengthened its relations with Britain by entering a formal alliance. The treaty was limited to the Far East and reflected the mutual interest of both Britain and Japan in containing Russian expansion in China and Korea by providing Japan with guaranteed great power support in the 1904-5 war. As well as committing Japan to support British plunder in China, the Alliance also required Japan to support Britain if its control over India was threatened by another power.[19]

The perspective of Australia’s ruling class was sharply at variance with that of its British mentors. Some even argued that the Japanese were using the Alliance to lure the Royal Navy out of the Pacific. The truth was the opposite – with Japan seeking from Britain an undertaking that it would maintain a fleet in the Far East superior to that of any other power. Many of those supportive of the treaty still saw it in terms hostile to Japan – that the treaty was the best way to restrain Japanese ambitions. The history of Russian invasion scares meant that when the 1904 war broke out, there was widespread support for a Japanese victory. Despite the concern that had emerged about Japan, it was still seen as a second-rank power and if it weakened the Russian threat, then that was all to the good. The Japanese victory unleashed the opposite dynamic. The leadership of the anti-Japanese push belonged to the racists and ultra-nationalists leading the Labor Party, which began agitating against Japan from early on in the war. According to Sissons,

the Labor weekly, the Tocsin, greeted the outbreak of hostilities with the comment that a Japanese victory would produce in Japan the demand for imperialist expansion of which Australia would be the most likely victim…[and] also make stronger demands for the modification of the White Australia policy.[20]

The Labor poet Henry Lawson’s reaction was to appeal to the tsar’s army – the army of semi-feudal reaction, of anti-Jewish pogroms, the army of the Bloody Sunday massacre of January 1905 – to stand firm:

Tis the first round of the struggle of

the East against the West,

Of the fearful war of races – for the

White Man could not rest

Hold them, IVAN! staggering bravely

underneath your gloomy sky;

Hold them, IVAN! we shall want

you pretty badly by and by.[21]

At the start of hostilities, the Liberal-Protectionist Prime Minister, Alfred Deakin, ridiculed the idea that a victory by Japan would encourage expansion towards Australia. But three weeks after the battle of Tsushima, in May 1905, which saw Japan virtually destroy the Russian fleet, Deakin made his first serious statement on defence since Federation; it was also the first by the leader of a non-Labor party in which Japan enjoyed a prominent place as a defence threat. Due, he argued, to the growth of the navies of the US, Germany and Japan, Australia was now within striking distance of sixteen foreign naval stations, the strongest of which was Yokohama. “Japan at her headquarters is, so to speak, next door while the Mother Country is many streets away.” His response was to propose increasing the annual expenditure on local marine defences from £44,000 to £350,000.[22] According to Sissons, the war also made a profound impact on the top echelons of the military, and especially Sir Edward Hutton, the highest ranking soldier in Australia – General Officer Commanding the Military Forces.

It is impossible to view the military situation in Australia…without grave misgiving. The victories of the Japanese arms within the last four months have astounded the whole civilised world.[23]

Indeed, it led him to embrace, for the first time, the possibility that Australia could at some point be invaded, an idea that the military chiefs had historically rejected as alarmist. Specifically, Hutton raised the possibility that British naval supremacy could be lost – not to the Japanese alone, but in the context of a combination of great powers hostile to British interests. This would open the door to Japan gaining control of the Pacific. Later that year he warned that “the people of China and Japan were casting longing eyes on the rich Northern Territory”.[24]

In the press and society generally, fear of Japan appears to have still been the view of only a minority, albeit a substantial minority, during the war and shortly afterwards. Nevertheless, the armed forces chiefs and certain key politicians had taken the issue up and within little more than a year, they had won the argument. 1907 marks, as Sissons puts it,

the period in which fears of Japan became acute and widespread finding expression in great increases in naval and military expenditure, in apprehensive ministerial statements, in numerous allegations of Japanese espionage, and in invasion as a popular theme in imaginative literature.[25]

We can trace the rising fear of Japan in the debates around the principle of compulsory military training. The idea was traditionally associated with the Labor Party and specifically with the future prime minister, William Morris Hughes, who moved for it in private members’ bills in both 1901 and 1903. At neither time did he gain much support, even from his own party; nor did another attempt in 1903 by a Protectionist senator to introduce cadet training. A new attempt in 1906 had the support of the leadership of the Protectionist party and a minority within Labor, but the Free-Traders were still strongly opposed and it was defeated. By 1907, most of Parliament had swung around to support Hughes, and Hughes himself had shifted his argument. Whereas in 1901 and 1903 he had talked of threats in general from Europe and Asia, he now focused primarily on Japan and the “White Australia” policy, arguing, “Nothing but the fact that America possesses a population of 80 millions…does, I believe, cause Japan to hesitate to declare war”.[26]

He was supported by the Minister for Defence, Ewing, who had previously condemned Hughes’ proposals as extravagant. Now:

Every sane man in Australia knows that, if this country is to remain the hope of the white man, it must be held, not only by the power of Australia alone, but by the might of the white man in all parts of the world.[27]

Likewise, in the Senate, George Pearce, who would soon become Defence Minister in the Fisher Labor government, documented his own conversion:

There was a time when I deprecated any attempt by Australia to take any part in militarism. It is only the developments in Asia…that have converted me… I have never feared, nor do I now fear, the invasion of Australia by any European nation… But I do recognise that in the East there are peoples alien to us in race, religion and ideas, industrial and social, and that if we believe in our ideals, if we want to establish the industrial Commonwealth which we hope to establish here, we must shut our doors against races so foreign to us as the Asiatic races are. The only doctrine that these races respect is the doctrine of force. Our White Australian legislation is so much waste paper unless we have rifles to back it up…[28]

Legislation passed in 1909 and 1910 made compulsory military training law. Likewise, the debates that had continued over a decade about whether or not there should be a separate Australian navy were now resolved firmly in the affirmative.

The victory of protectionism

The hegemony of paranoia about Japan also resolved, for decades to come, one of the great, historic debates that had divided the ruling class – free trade vs. protection. In the 1880s, there had been an international tendency towards protectionism – with tariffs imposed in Germany in 1879, Russia 1881, France and Austria 1882 and the McKinley tariff in the US in 1890.[29] This was in part a response to economic crisis – the so-called “Great Depression” of the l870s and 1880s – and the tendency for profit rates to fall (which Marx had predicted). There were actually two responses to this crisis – one, as Chris Harman put it, “using the forces of the national state to carve out areas of economic and political privilege for themselves overseas”. This was the “imperialist” option that the British took because they were best able to benefit from it.[30] This led to all kinds of moves to tighten up the empire and stress its racial basis, and provided the foundations for “White Australia”. The other response involved the rapid centralisation of capital into giant monopolies and trusts – the German approach. Bukharin saw in this a tendency towards “state capitalism”.[31]

What characterised both approaches was the central involvement of the state in guaranteeing the conditions for continued capital accumulation. And as the benefits of empire and centralisation diminished, each side turned to the strategy of the other – the Germans and Americans to imperial expansion and the British to monopoly and state intervention in the economy. In both strategies, tariffs became important as a way of protecting the national industrial base that was an essential provider for the military. In Australia, state capitalism had been central for decades. Assisted immigration, a central feature since the 1830s, was a large-scale state project. By the 1880s, upwards of 50 percent of fixed capital expenditure was state directed – and this in a raging boom! As imperialist rivalries accelerated, the colonial ruling classes sought to tighten their links with British imperialism from which came their ultimate guarantee of capital, markets and military protection.

But the colonies had been divided over protectionism. In NSW the “free trade” wing was stronger, but in Victoria, with its greater manufacturing base, protectionism was hegemonic. It is highly significant that the successful push for Federation was initiated in 1889 by the “free trade” premier of NSW, Henry Parkes, who was sufficiently concerned about the “defence” situation to entertain a compromise on protection. The extraordinary and prolonged economic crisis of the 1890s savagely weakened pastoral capital (the cornerstone of free trade) and strengthened the “protectionist” current. Nevertheless, in the early federal parliament, there were broadly three parties: Labor, Protectionist and Free Trade, with Labor itself split on the question.

The rise of Japan unleashed an inexorable dynamic towards protectionism. The military question emphasised the importance of manufacturing industry, and of both population (which in turn also emphasised the importance of industries in which to employ people) and “closer settlement” of the land. In 1909, with the anti-Japanese paranoia at its height, the Free Traders entered a coalition with their supposedly greatest enemies, the Protectionists. Partly this was a reaction to the rise of Labor, a development which pushed the ruling class parties closer together; but partly it was because the Free Trade position, in its economic and military components, had almost completely lost ground. A similar development occurred within the Labor Party, which had also traditionally had a minority Free Trade wing, led by people like Chris Watson and William Morris Hughes. The rising paranoia towards Japan strengthened the Protectionist/militarist/populate-or-perish wing. At the 1905 interstate conference, the party leader Watson reflected:

It had been brought home to him very strongly during the last year or so that there was a great necessity for them to take some step in this regard (i.e. adopting Protection). They had a great need to do something in view of the developments of the North – colloquially known as the Far East – to ensure a greater population for Australia. It was a great menace to have so much unpeopled territory when there were nations now slowly unfolding themselves as great powers and who would exercise in the Pacific an almost dominating influence on the destinies of Australia…[32]

Hughes, who more than any other individual came to be identified with Australian hostility to Japan, followed a similar evolution. According to his biographer, L.F. Fitzhardinge,

So far as the “White Australia” policy was economic, they [the Labor free traders] came to see that tariff protection…was its necessary complement.[33]

This period, in which anti-Japanese paranoia became hegemonic, was the context in which the American “Great White Fleet” visited Australia. In the words of the West Australian newspaper,

To Australia, the lone guardian of white civilization in the Pacific, the message that comes cannon-tongued by the swift and stalwart messengers of the deep has but one import – an assurance of amity charged with power.

Or the Advertiser,

Our White Australia policy rests upon well founded grounds, partly racial, partly economic, which imply no disrespect for the many virtues of the Japanese; and if we fear that at some time in the future we may have to fight for our right to hold the great island continent, it is because we attach due importance to the tremendous pressure of population in determining future Asiatic movements… We believe that we see more clearly than the British people do, the real nature and extent of the Oriental menace.

Finally, an indication of the degree of paranoia in the population at large can be gained by looking at the popularity of the invasion literature that erupted between 1908-11. It needs to be emphasised that such themes, which are inherently pretty gruesome, cannot be commercially successful unless they reflect widespread concerns. The magazine that published most of them, the Lone Hand, was a widely read monthly published by The Bulletin. Most of the writers were, like Lawson, not from the extreme right, but firmly within the Labor tradition. The most substantial work was The Australian Crisis, a novel by C.H. Kirkness, serialised in the Lone Hand, which also published “First Blood” by Boyd Cable and “The Deliverer” by Aldridge Evelyn, described by Sissons as typical:

Britain, at war with Germany, withdraws her warships from Australia to Hong Kong where they are bottled up by Japan. A Japanese battle fleet, despite the gallant resistance of [Prime Minister] Fisher’s four destroyers, arrives off Sydney and demands “a treaty which will allow every Chink and Jap under the sun to land in Australia and become a citizen”. Just as the government are about to follow Britain’s advice and surrender, a patriotic squatter comes forward with a submarine which he had the forethought to import and assemble secretly. The hero [is] a naval officer…[who] destroys the enemy fleet. His inspiration in this crisis is…his daughter–“Good Lord, man! Her Australia shall be a white one!”[34]

The First World War

In August 1914, the growing tensions between the great powers erupted into world war. Most histories of Australia’s involvement cover the fighting in France and the Middle East, the enormous casualties suffered (some 60,000 dead and 150,000 wounded out of a population of 5 million) and the huge struggles that erupted when the Hughes government tried to introduce conscription in 1916 and again in 1917. This rendering of history is at best one-sided, and at worst, dishonest. Although the war was formally against Germany and its allies, Australia’s political leaders were as much concerned about the expansion of their ally, Japan – indeed the “threat of Japan” underpinned their willingness to fight Germany.

The rising tide of anti-Japanese paranoia that erupted between 1905 and 1910 had been partially stilled by the renewal of the Anglo-Japanese alliance in 1911. Many Australian politicians had opposed the alliance, but some of the most anti-Japanese supported it, seeing in it a brake on Japan’s supposed ambitions. With the eruption of the First World War, all these contradictions intensified. The war brought into the minds of Australia’s politicians the chilling possibility that a war against Britain involving a combination of powers could see much of the British fleet in the Pacific withdrawn and Australia left vulnerable to Japan’s supposedly predatory designs. Indeed, an instructor at Duntroon, who approached the Governor-General, Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson, for assistance in getting a release to serve with the British army in France, was told that “the war would be over before I could reach home and that my duty was to remain in Australia to train the young officers for the inevitable war of the future with Japan”.[35]

For their part, five days after it started, the Japanese entered the war on the side of the British. The Japanese navy helped escort Australian troop ships to Gallipoli and the Mediterranean and Japanese ships patrolled Australian coastal waters, releasing Australian warships to hunt down their German rivals. This co-operation was only agreed by Australia with great reluctance and news of it was suppressed.[36] Also suppressed was some anti-Japanese agitation. The Labor government, led firstly by Andrew Fisher and from 1915 by William Morris Hughes, lived in permanent fear that Japan would abandon its alliance with Britain and go over to the German side. Every expression of pro-German feeling in Japan (and there was a strong pro-German wing in ruling class circles) intensified this.

Far from leading to a smoother relationship, their war-time “cooperation” brought Australia and Japan rapidly into conflict. Right at the beginning, both Australia and Japan responded to British requests to seize German-controlled islands in the Pacific, in order to make German naval operations more difficult. Australian forces seized New Guinea (the northern half of what is now the mainland of PNG), Bougainville, the German New Hebrides (now Vanuatu), and when they seized Rabaul, the German administration formally surrendered a series of islands north of the equator which had been administered from Rabaul – the Marshalls, Carolines, Mariannes and Palau.

Because Australia lacked the forces to spare to physically grab these, the Japanese navy did instead – partly to close down German communications, partly to set up their own radio network, and partly to stake their own claim to control after the war. This drove the Australian government into a frenzy, and it began discussing the costs and benefits of insisting on Australia having long-term control of these islands – all of them thousands of kilometres from the tip of Cape York. It was not that the islands possessed much commercial value; it was a question of keeping the Japanese out. Britain’s refusal to insist on a Japanese handover of the islands (it, too, was concerned to keep the Japanese government on side) added to Australian government concerns.

This was compounded in early 1915 by a Japanese request, backed up by Britain, that Australia adhere to the Anglo-Japanese Commercial Treaty of 1911. The Japanese wanted to consolidate the expansion of trade the war had brought for them, and to improve their fairly dismal relations with the Australian government. Ratification would give Japan “most favoured nation” status in trade and allow the free right of entry and residence for the citizens of each country in the land of the other. The Japanese government made it clear it was prepared to respect the horrific racism of the “White Australia” policy. The Australian government was firmly opposed to such a proposal. There was no way they were going to allow Japanese goods to compete on the same basis as British – indeed, some Labor members wanted the tariff against Japanese goods increased, not cut – and there would be absolutely no way they were going to compromise the idea of the “White Australia” policy, even if the effect in terms of Japanese migration was minimal.

To Hughes and the Australian government, these two Japanese initiatives confirmed “all our fears – – or conjectures – that Japan was and is most keenly interested in Australia”. According to Fitzhardinge, “One of Hughes’ main reasons for going to London (in 1916) had been his concern about Japan’s activities in the Pacific and her post-war position there in relation to Australia”.[37] “Australia greatly dreads Japan’s future aims,” Hughes told one confidant during his trip over.[38]

In London itself, the Japanese ambassador arranged to meet Hughes to try and allay his fears; pointing out that Japan’s main aim was “to remove the irksome restrictions on carrying on business, entry and residence imposed on the Japanese in Australia”. Rather than allay any fears, Fitzhardinge writes that Hughes “found his suspicions of Japan’s real intentions confirmed…fear of Japan had become an urgent apprehension amounting almost to an obsession, the more powerful because it could not be publicly expressed”. In Adelaide, on his way back from London, the prime minister made an emotional speech on the danger to “White Australia”:

We have lifted up on our topmost minaret the badge of a white Australia, but we are, as it were, a drop in a coloured ocean ringed around with a thousand million of the coloured races. How are we to be saved? What arrogance and what futility it would be to emblazon White Australia on our banners if we are not prepared to fight for it, and how are five to fight a thousand, valiant though they may be? Does not the spectacle of the British Empire today fighting in a common cause drive home…the great lesson that we stand with our feet firmly fixed on the temple of liberty only so long as we are part of the British Empire.[39]

This was the beginning of Hughes’ campaign to introduce conscription. On 31 August, 1916, he called a secret session of both houses of Parliament to report on his trip and whip up support, among politicians, for his paranoid views on Japan. Major E.L. Piesse, who was Director of Intelligence in the Prime Minister’s Department at the time, later wrote:

The proceedings were not published, but it was…widely believed that an authoritative statement had been made to the meeting that Japan would challenge the White Australia policy after the war, that Australia would need the help of the rest of the Empire, and that if she wished to be sure of getting it she must now throw her full strength into the war in Europe.[40]

So conscription was proposed – and 60,000 young Australian men and women died – not out of colonial servility towards Britain, but to defend the empire on which Australian capitalists depended for military defence, and specifically to strengthen the position of Australia’s imperialists in their rivalry with Japan, a rivalry that was largely one way and largely aimed at making sure that no potential challenger emerged to British/Australian/American domination of the region.

The attempt to introduce conscription led to the sharpest political struggles in Australian history. The working class radicalisation of the period 1916-1920 was the greatest we have so far seen, with a significant minority seeking some kind of revolutionary challenge to the system. A measure of this was that Hughes, the prime minister, was expelled from the Labor Party over conscription – an incredible act for such an electorally oriented organisation. This was the environment in which the revolutionary syndicalists of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) flourished. Unlike virtually the entire history of the Australian left to that point, the IWW was anti-racist. But the anti-conscription campaign involved far wider forces than the IWW. The Labor Party continually attempted to link its opposition to conscription to its anti-Japanese racism. So the Labor Call, in an article “Ten Reasons for Voting No”, listed the first as:

I will vote “No” because I believe in keeping Australia a white man’s country. “Yes” would commit Australia to sending 16,500 men away monthly for an indefinite time. Soon…the country would have to resort to importing labour.[41]

Among Labor MPs one of the most common arguments was that Australians were fighting the wrong war. This argument was the staple offering of leading Labor anti-conscriptionist, J.H. Catts, who got himself summonsed at least seven times for “statements likely to prejudice…relations…with a foreign power” by making comments such as:

The Pacific Ocean was assuredly going to be the scene of the next great war, in which the struggle would be between the white and yellow races. Yet today there was the sorry spectacle of the great white races battering each other to pieces… He could not sufficiently emphasize Australia’s deadly peril from the Japanese menace.

It is worth looking, then, at the political dynamic of the war in Australia. The imperialist carve-up of the world meant that the emergence of any new power would challenge the position of the old powers, since it could not win markets and colonies without threatening the markets and possessions of the existing powers. As the advance base of British imperialism in the region, Australian bosses and their ideologues, including the Labor Party, viewed Japanese successes with far greater alarm. It was irrelevant that Japan expressed absolutely no hostility towards Australia, irrelevant that its territorial ambitions were directed towards Korea, Mongolia, and the seas in its immediate vicinity. The sheer existence of a rival power in the region was alone cause for alarm. And not just alarm.

Rising fears of Japan drove Australian nationalism more explicitly behind the British shield – hence the huge commitment of troops to Europe and the phenomenal attempts to force conscription through – and deepened Australian racism. But these fears also led to the intensification of specifically Australian imperialism. As we have seen, Australian politicians had always insisted that Britain should seize as much territory in the Pacific as possible. Rising fears of Japan now led Australian governments to demand an extensive area of territorial control for themselves. At the Versailles “Peace” Conference in 1919, Prime Minister Hughes, now leading an anti-Labor government, demanded the right to annexe all the South Pacific territories seized from Germany – New Guinea, Bougainville, Rabaul.

Hughes had been appalled to find out that in 1917, desperate to keep Japan as part of its imperialist bloc, the British had guaranteed to support Japanese claims to control the islands it had seized in the North Pacific. “British party politics”, he complained, “ignore Imperial interests. There is no Imperial Government in this great crisis… I am trying to do what I can…to prevent any peace that does not…safeguard our interests in the Pacific”.[42]

Against the background of revolution in Russia, revolutionary upheaval right across Europe, and rising nationalist agitation in the colonial world, the most intelligent imperialist politicians, led by US President Woodrow Wilson, established the new League of Nations. Their aim was at least partly to dampen down the widespread perception that the war had not been for “civilization” but markets and colonies. Wilson proposed a new system of “mandates” which would place the colonies seized from Germany under the formal control of the League, which would hand over their administration to one of the victorious powers. Despite the transparency of a system of “mandates” run by the existing colonial powers, Hughes fought tooth and nail against applying them to New Guinea. He fought for full annexation of these territories.

Strategically the Pacific Islands encompassed Australia like a fortress. New Guinea was…only 82 miles from the mainland. South East of it was a string of islands suitable for coaling and submarine bases from which Australia could be attacked…

Furthermore, under the proposed mandate system, Australia would be forced to apply the principle of the “open door” and allow Japanese and other peoples to visit and live there, in which case the territory would, he argued, become “a Japanese or Japanese and German country” within ten years.[43] It is ironic that under German control, with no restrictive legislation, New Guinea failed to attract vast numbers of either Japanese or Chinese – merely 103 and 1,377 respectively in 1913.

Wilson was forced to respond that if annexation was allowed, the League of Nations would be discredited from the start. The result of Hughes’ efforts was the creation of a special class of mandate to apply to South West Africa (Namibia) and certain Pacific islands which, “owing to the sparseness of their population or their small size, or their remoteness from the centres of civilization, or their geographical contiguity to the mandatory State” would be best administered “under the laws of the mandatory State as integral portions thereof”[44] –in other words, effective annexation. For Billy Hughes, the importance of the wording of the C–class mandate was that it meant the “White Australia” immigration restrictions would apply to its territories. They had the right now, in international law, to keep the Japanese out. Indeed, after the mandate was issued, the first legislative act of the Commonwealth with respect to the territory was to apply the Immigration Restriction Act. Thus Australia’s anti-Japanese paranoia provided the cover under which South Africa got complete control over Namibia. In the German territory of New Guinea, too, the transfer from German to Australian control was a massive step backwards. Whereas the Germans had, against the protests of German settlers, allowed New Guineans to engage in cash cropping, the new Australian administration moved to either restrict or ban it.

Whereas Germany, with its strong industrial economy, wanted to develop New Guinea’s raw material exports, Australia, as a raw material exporter itself, discouraged any production that could compete with Australia’s. And the maximum flogging allowed for breaches of labour discipline on the plantations was promptly doubled – from ten to twenty strokes. Unlike Germany, Australia’s economy was industrially backward. Every penny spent in the colony was resented. The first government school on Bougainville was only opened in 1961. Australia’s interest in New Guinea was almost entirely military. Thus, as a result of its hostility towards Japan, it insisted on control of PNG and then kept it in the most terrible poverty and backwardness. Every Australian government since – including the Hawke government today – has regarded PNG as a fundamental military asset and has used both money and armed force to maintain its dependence on Australia.

Finally, in response to the incredibly racist treatment their citizens met in the West, the Japanese delegation at Versailles proposed that the Covenant of the League of Nations uphold the principle of racial equality. Baron Makino moved:

The equality of nations being a basic principle of the League of Nations, the High Contracting Parties agree to accord, as soon as possible to all alien nationals of States members of the League, equal and just treatment in every respect, making no distinction, either in law or in fact, on account of their race and nationality.[45]

It is so completely symbolic that it was this declaration against racism that brought Australia and Japan into open and direct conflict for the first time – with Australia’s prime minister defending the right to racism because of paranoia about Japan. Of course the Japanese ruling class itself was racist – most especially towards Koreans. And it made it clear that the declaration was not to be a lever by which the League could interfere with the internal affairs of any nation. But had it been passed, even by the scoundrels who formed the League of Nations, it could have been a useful propaganda weapon against precisely those same scoundrels. It is significant that it was only Australia’s trenchant opposition that scuttled it. Hughes recognised that any statement against racism would be a weapon against immigration controls, especially Australia’s, the most openly and deliberately racist in the world.

The Japanese delegation proposed amendments that were acceptable to all the great powers – and even to the South African Prime Minister, Smuts. Hughes held out. And to put pressure on Wilson, he set out to inflame anti-Asian feeling on the American West Coast. In the end he succeeded. But this “victory” was not without its costs. The successful Australian agitation against the anti-racism clause was widely reported in Japan and, justifiably, aroused great anger. This was on top of anger at a number of comments and speeches by Australian politicians, in particular one by Hughes in 1918 in which he declared Australia’s “Monroe Doctrine” – named after the famous imperial declaration of US President Monroe which asserted the primacy of US interests in Latin America – a speech aimed directly and accusingly at Japan:

Hands off the Pacific! is the doctrine to which by inexorable circumstances we are committed. We rejoice that France has interests in the Pacific, and that Holland…is our neighbour in Java and New Guinea.

In the wake of all this, Major Piesse, the Intelligence expert, drew a gloomy assessment from Versailles, deploring “the barren victory over racial discrimination” and observing:

We have been perhaps the chief factor in consolidating the whole Japanese nation behind the imperialists.[46]

The Second World War

Today’s anti-Japanese agitation draws very heavily on the imagery and tradition of the Second World War, which is widely seen to have been a struggle by “civilisation” and “democracy” against Japanese treachery, militarism and barbarity. No-one beats the drum of that war more conscientiously than that supposed peace-monger, Helen Caldicott.

It is not racist for me to ask why we fought World War II against the Japanese, 45 years later, we seem ready to allow annexation of our land by that very nation for which our fathers died trying to prevent from commandeering our natural resources.[47]

She has repeatedly made similar comments – including to a rally of 7,000 in Hobart in March last year protesting against the plan to build the Wesley Vale pulp mill.

When the Melbourne Herald asked its readers to phone in their opinions of the proposed Multi-Function Polis, it received “hundreds of calls”. In the end, they printed a sample of thirteen responses – three were for the MFP and ten against. Eight of the ten explicitly mentioned Japanese involvement as a major reason for opposition and the other two attacked the involvement of “foreigners” – a code word for the Japanese. Of the eight whose short responses mentioned Japan, three specifically referred to the war. Pat Glassner of West Brunswick was quoted as saying, “let’s never forget the Japanese were the aggressors in the 1941-45 Pacific war and many Australians still bear the scars” and John Robinson of Toorak attacked “the businessmen who support this… [They] are un-Australian and have no respect for the sacrifices and the ill-treatment that our servicemen took from the Japanese in World War 2”.[48]

Every time the question of “Japan” has been raised at Sydney’s “Politics in the Pub”, someone has raised “the rape of Nanking”, or told those of us “too young to remember” how they saw “Japanese soldiers skinning people alive”. Somehow they always manage to avoid mentioning how people’s bodies were melted when the Allies dropped the bomb on Hiroshima – in other circumstances a favourite left talking point. When Abe David, co-author of The Third Wave, was interviewed by Sydney’s most notorious racist, Ron Casey, he too drew on history:

The Japanese have got a new long-term plan for Australia. It’s not new. In the Second World War…they looked to Australia as being – along with Manchuria and China – the key part of Asia that could supply them with most of their resources…[49]

In other words, the Japanese have always had ambitions to take over Australia; today they’re doing it through buying up the country. Our freedom and independence are threatened; we have to rally to the defence of the nation and stop them. This argument is a mixture of racism, paranoia and falsehoods. First, the major falsehood – that Japan wanted to take over Australia during the war. It was a key plank of government propaganda at the time and is still widely believed. Yet it was nonsense at the time and has since been decisively refuted by examination of captured Japanese records. David Sissons expressed the historical consensus already achieved by the mid-1950s when he wrote:

At no time – either before the Second World War or during it does Australia appear to have figured in Japanese plans for occupation or exploitation.

The plan as put into operation in December 1941 was to seize and establish a defensive [!] perimeter for the rich “Southern Resources Area” along the line – the Kuriles, Marshalls, Bismarcks, Timor, Java, Sumatra, Malaya, and Burma. Australia was outside this region. The invasion force which was turned back in the Coral Sea was not bound for Australia but for Port Moresby which the Japanese, surprised by the ease of their initial successes, had hastily decided to take in order to provide additional defence for their main base at Rabaul. The advance to Kokoda had the same limited objective.[50]

But to sustain racist myths is more important than the truth. So Wheelwright and David tell of an individual called Ken Sato, who

had been chosen as the Chief Civil Administrator for Japanese-occupied Australia…after the war he told Australian correspondent Denis Warner that the invasion of Australia was scheduled for the autumn of 1942…[51]

What is their source for this story? Was Ken Sato talking about serious plans or was it wishful boasting? Wheelwright and David get the story straight out of War on the Waterfront by that well-known Japan hater, Rupert Lockwood. What they neglect to acknowledge is Lockwood’s admission that:

In the decisive talks in Tokio the Japanese Army pointed out that Australia was twice the size of occupied China. Conquest would demand diversion of the main naval forces at Japan’s disposal; the US Navy had shown it was far from finished and could block supply lines and the Army could not provide twelve infantry divisions felt necessary, nor were the required 1,500,000 tons…of shipping available.[52]

In their desperation to concoct anti-Japanese propaganda, even Rupert Lockwood has to be edited! But in the main, the anti-Japanese argument rests on half-truths rather than outright lies. We are told the Japanese were brutal and barbaric; we are not told that the Allies were sometimes worse. We are told of brutal treatment in Japanese prisoner of war camps; we are not told that the Allies preferred not to take prisoners. We are told the Japanese were aggressive and treacherous imperialists; we are not told that Asia was already dominated by brutal and powerful imperialists, that Japan did not want war with America.

Most importantly, the established mythology lets the real villains off the hook. The war was not a product of Japanese “aggression”, but imperialist rivalry, of which Japanese aggression was but one significant component. Blaming the Japanese legitimised the expansion of American and Australian military power throughout South-East Asia – in other words, strengthened the imperialist system, the cause of the war. The racist attitudes aroused by blaming the Japanese helped tie Australian workers to their exploiters. They conditioned Australian workers to accept massively raised levels of exploitation during the war, to accept huge wartime casualties, and finally to positively welcome the use of the atomic bomb, the ANZUS treaty, the Korean War and the invasion of Vietnam.

The road to Pearl Harbour

On the evening of 7 December 1941, Japanese planes bombed Pearl Harbour in the American colony of Hawaii, thus beginning the Pacific War. Immediately the Western propaganda machine leapt into action. Japan’s action was “treacherous”, “a day that will live in infamy”, and worse. This myth of Japanese “treachery” is enormously potent still today. However, it is exactly that – a myth. The truth is that it was the American administration that decided on war. On 25 November 1941, the US Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson, wrote in his diary with regard to Japan:

…the question is how we should manoeuver them into the position of firing the first shot without allowing too much danger to ourselves.[53]

Indeed, the administration had been warned three days in advance, by Australia, that a Japanese fleet was headed towards Pearl Harbour. Instead of issuing the fastest possible warning, they conspired to delay the message to their fleet there and sent it by slow, commercial channels rather than through military communications.

By late 1941, the US had agreed to enter the war on the side of the British after forcing Churchill to accept that the post-war world would see the British Empire dismantled and American interests dominant. The problem facing Roosevelt was that the American population was largely hostile to US involvement in the European war. Indeed, Roosevelt had been forced to pledge himself to no involvement during the presidential election of late 1940. Stimson revealed the motives of the administration at the Congressional committee investigating Pearl Harbour in 1946:

In spite of the risk involved, however, in letting the Japanese fire the first shot, we realized that in order to have the full support of the American people it was desirable to make sure that the Japanese be the ones to do this…[54]

Beard argues, then, that the tactic of the US administration was to use war in the Pacific as the means of involving itself in the world war more generally – without which it could not dominate the post-war world. Of course, it would not have been interested in war in the Pacific had it not been seriously concerned with the rapid growth of Japanese imperialism: its conquest of whole sections of China, its seizure of French Indo-China and its obvious preparation to use the European war to expand its empire. Again, the US was not the slightest bit concerned for “democracy” or the national rights of the countries seized by Japan – its own empire (as well as those of its allies) were testimony to that. Its central concern was to prevent the expansion of a powerful rival.

In August 1941, the US publicly warned Japan against taking “any further steps in pursuance of a policy or program of military domination by force”. According to Charles Beard:

The Premier of Japan, on September 6, 1941, informed the American Ambassador in Tokyo that he subscribed fully to the four great principles of American policy laid down in Washington. Then President Roosevelt and Secretary Hull declared that this was not enough…[55]

Realising the imminent danger of war inherent in the US declaration, the government of Prince Konoye repeatedly sued for a peaceful settlement. The US ambassador in Tokyo, who had been in the post for a decade, laid great stress on the willingness of the Japanese government to negotiate peace. Furthermore, he warned that the delaying tactics and the insistence by Washington that line by line negotiations take place before any meeting would discredit the Konoye cabinet. He warned Roosevelt:

The logical outcome of this will be the downfall of the Konoye cabinet and the formation of a military dictatorship which will lack either the disposition or the temperament to avoid colliding head-on with the United States.[56]

Was Japan’s peace initiative just a manoeuvre? The US had by now broken the Japanese communications code and intercepted messages that showed that even the new Tojo government was anxious to settle with the US, and indeed, for a few weeks, the US toyed with negotiations. Then, around 25 November, they settled decisively on war. We don’t exactly know why; what the balance of argument was. We do know that the British government, having secured a promise from Roosevelt that he join them in the war against Germany, was also pressing the US to take action against Japan in the East. Japan’s expansion was threatening Britain’s vast empire, and it no longer had the forces to maintain its interests. The next day, 26 November, Secretary of State Hull handed the Japanese a humiliating ultimatum which insisted:

The Government of Japan will withdraw all military, naval, air and police forces from China and from Indo-China…[and support no] government or regime in China other than the National Government [of Chiang Kai-Shek]…[57]

Now socialists, of course, were strongly against Japanese imperialism and militarism. But we were (and are) also against British, American and Australian imperialism. And we are against any attempt by any of the great powers to transform their rivalry into war. It would have been just as outrageous for the Japanese imperialists to insist that the US government withdraw from the Philippines and Hawaii, the British from India, Hong Kong, Malaya, Singapore, etc. as the price for avoiding war. It has to be emphasised that the humiliating ultimatum that led to war came from our side, that Pearl Harbour was the result of American, not Japanese treachery. The Japanese government felt they had been left only two stark options: to retreat and subordinate themselves to the Americans, or to take the risk that war involved. In its weekly intelligence report of 12 December 1942, the British Admiralty wrote:

had she not gone to war now, Japan would have seen such a deterioration of her economic situation as to render her ultimately unable to wage war, and to reduce her to the status of a second-rate Power.[58]

Being by far the weaker power, it made sense for Japan to strike first and strike hard in the hope that the gains made would give them some chance of coming out of the catastrophe no worse off. When Stimson, the Secretary for War, asked Hull on 27 November about the negotiations with Japan, the response was, “I have washed my hands of it and it is now in the hands of you and Knox – the Army and the Navy”.[59] This was a full ten days before Pearl Harbour.

However, in seeking an explanation for the causes of a war, it is completely fatuous to argue over “who fired the first shot”. War is an extension of politics, and a war as profound as the Second World War only grows out of profound and otherwise irresolvable rivalries. The common explanation for the war is that Japanese expansionism made war inevitable. You only had to look at the seizure of Manchuria in 1931, the contrived and brutal war with China from 1937, the Axis Alliance with Germany and Italy and the thrust southward which began in Indo-China in 1940. Pearl Harbour was just part of a pattern. And of course, this is, in a sense, true – but dishonest at the same time. The reason that Japanese expansion led to war is that it ran slap bang into the interests of the existing great powers. It would be just as honest to say (as the Japanese did) that the war was caused by the refusal of the declining imperialists, such as Britain and France, to give up some of their colonies – in which their rule was as brutal as anything dished out by Japan – to the virile, new powers in the world. Building a Japanese empire wasn’t simply an act of greed, it was a response to the world situation Japan’s rulers found themselves in – a world of great powers, bolstered economically and militarily by their colonial possessions. Commenting on Japan’s annexation of Korea in 1910, James Crowley wrote:

It seems manifest, in retrospect, that the absorption of the Hermit Kingdom [Korea] was practically dictated by the nature of European rivalries, especially the advance of Czarist Russia into South Manchuria and the projected construction of the trans-Siberian railway.[60]