Our unions in crisis: how did it come to this?

Playback speed:

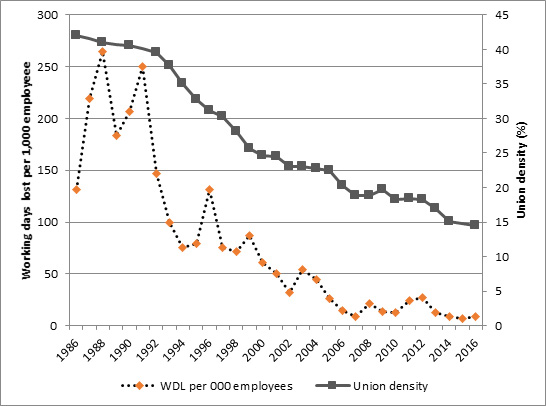

Trade unions in Australia are facing the biggest crisis in their existence. Membership coverage – the ratio of unionists to workers – has fallen for more than three decades and now stands at just one in seven, down from one in two in the early 1980s.[1] From being one of the world leaders in union coverage outside Scandinavia, Australian unions have experienced the most rapid decline of any Western country. Industrial relations lawyer Josh Bornstein is right to argue that “The tipping point passed long ago. Australian trade unions are fighting for their survival”.[2]

Areas that were once at the forefront of unionism have faded almost to nothing. Outside a few pockets, there are large swathes of manufacturing with no more than a token presence of union members – less than one in ten workers in the machinery and equipment industry are now unionists. The result is that membership of the Australian Manufacturing Workers Union (AMWU) has collapsed from more than 200,000 members in 1995 to 80,000 in 2016. Tens of thousands more are expected to go within five years, with the union predicting just 40,000 dues-paying members by 2020.[3] The Pilbara iron ore industry, once a union stronghold, has seen unionism virtually disappear. In coal mining, another former union bastion, coverage has fallen by more than half, and the same is true in the utilities (electricity, gas and water) and construction: outside big projects, mainly in the central business districts, unionism in the construction industry has been purged. Finance and insurance, never a militant area but one with relatively high union coverage, has seen coverage drop dramatically, likewise communications.

Particularly worrying is that union coverage is both very low and dropping even more rapidly among younger workers. Union coverage is therefore likely to keep declining without dramatic change as those workers with some experience of union activism retire, giving way to a new generation without any knowledge of union struggle on the job – the 21-year-old who took part in the last big strike push of 1981 is now in their late 50s. The vital socialisation processes that have in the past inculcated new entrants to the workforce with union traditions are breaking down. The culture of unionism, once an important feature of working class life in Australia, has substantially broken down.

Little wonder that ACTU secretary Ged Kearney told a crisis meeting of union leaders in 2016 of her fear that unions could be reduced to “some quaint anachronism barracking from the sidelines” and “a national non-entity”.[4] For the right, of course, this prospect is welcome, with The Australian’s industrial relations writer Troy Bramston asserting that “the union movement is in terminal decline” as workers are “deserting unions in droves”.[5]

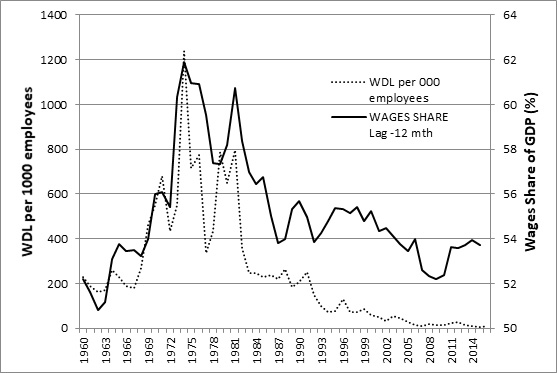

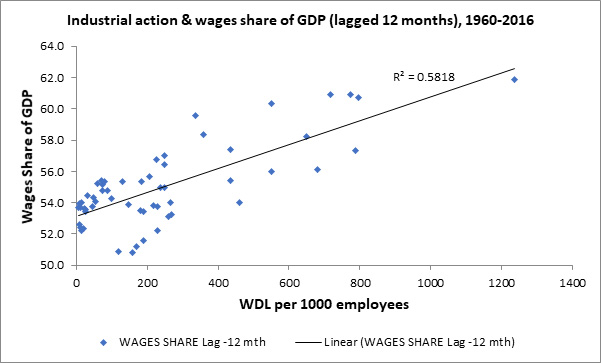

The dramatic weakening in union membership has contributed to the working class being pushed backwards. Real wages have fallen in recent years and the labour share of national income has sunk to its lowest since 1964. As numerous cases have now demonstrated, workers are being robbed of basic wage and superannuation entitlements, and penalty rates are rarely paid across hospitality and areas of retail dominated by small business and franchises.

As unions decline, so too does coverage of collective agreements. Between 2010 and 2016, the number of private sector employees covered by collective agreements fell from 2 million to 1.5 million, and in the public sector from 700,000 to 570,000, even while the workforce steadily grew.[6] For the most part, those no longer covered by collective agreements are now reliant on awards where wages are much lower.[7] The falling coverage of collective agreements, combined with meagre increases in the minimum wage applied to awards by the Fair Work Commission, has contributed to the rapid decline in the minimum wage relative to median wages over the past decade.

With weak or absent unions, the ability of management to boss workers around at the workplace has significantly increased. What employers and politicians call “restrictive practices”, which limit management’s assumed prerogative to direct workers on the job as to how work is done, what breaks are taken, what safety provisions are observed, how workers can be sacked or disciplined, what employment contracts workers are under (direct employment; labour hire; independent contractor) have all been whittled away. The absence of union intervention on the job also significantly increases the exposure of workers to unsafe work practices. More broadly, the decline of trade unions has removed an obstacle to successive governments stripping away social security entitlements that benefit the working class.

The decline of unionism also has important political and ideological effects. When unions fight, they overcome the atomisation of workers as individual voters and give the working class a collective voice and a platform to fight. They play an important role in shaping Australian politics, most obviously during the last term of the Howard government when the ACTU launched its Your Rights at Work campaign against WorkChoices. Or, more recently, in the marriage equality postal survey, where the unions, particularly in Victoria, established themselves as a significant force driving the “yes” vote, deploying many hundreds of volunteers across the cities. The unions possess roots in communities, in particular in blue collar workplaces, usually well out of the reach of small LGBTI campaign groups.

Finally, the absence of unions from so many industries dilutes a basic sense of working class identity and encourages individualism, with all of the toxic effects that go with that – crawling to the boss, doing down your workmates and so on. Fracturing solidarity at the workplace also opens the door in society more widely – in the parliamentary, media and educational spheres for example – for the ideas of the far right to grow.

The crisis of Australian trade unionism therefore has many damaging effects. The purpose of this article is to explain the roots of this crisis and to point to the potential for recovery. I start with a critical review of the strategies pursued by unions themselves over the past three decades, in particular their Accord with the Hawke and Keating governments. I then move on to some discussion of how unions can be revitalised, pointing in particular to the revival of class struggle and the growth of a larger radical left oriented to the working class movement.

The role of the Accord

The central argument of this article is that the decline of Australian unionism is in large part the responsibility of the trade unions themselves. And if it is decisions taken by the union movement itself that are to blame, so this requires a fight within the union movement to turn things around.

The adoption of the ALP-ACTU Accord in 1983 and its maintenance in various forms through to the defeat of the Keating government in 1996 must be understood as the single most important factor explaining the onset of sustained union decline.[8] The Accord entrenched class collaboration with the bosses, pushed aside strikes in favour of arbitration and appeals to the ALP, accelerated the destruction of independent shop floor union organisation and centralised power in the hands of the growing union bureaucracy. The Accord of course is long dead, but its legacy lives on in the strategies pursued by unions to this day.

This is not an uncontroversial argument. Peetz, for example, argues that the Accord delayed deunionisation in Australia because it held at bay hostile government attacks and prevented the Hawke and Keating governments from pursuing the kind of neoliberal agenda then being popularised by the Thatcher and Reagan governments.[9] It is worth spending a little time, therefore, to explain the role of the Accord in steering the union movement towards its current predicament.

The Accord was an agreement between the ALP and ACTU leaders by which the latter agreed to abandon industrial campaigns for higher wages and better working conditions in return for the “maintenance of real wages over time” through the mechanism of six-monthly indexation of award wages by the Arbitration Commission (the forerunner of the Fair Work Commission). The Accord also involved a commitment by the ALP leadership to an expansionary fiscal policy that would cut unemployment, an increased “social wage” (Medicare, social security payments, pensions), and the inclusion of trade union leaders in tripartite committees that would give them a voice in economic and industry policy.

The Accord was at its inception a brainchild of the left of the trade union movement, most notably the leadership of the Amalgamated Metal Workers Union (AMWU) and the Building Workers Industrial Union (BWIU). Key figures had been or were in one of the communist parties (e.g. Laurie Carmichael, Tom McDonald, John Halfpenny). The fact that it was a project identified with the left wing and more militant unions was central to its success. For any incomes policy to succeed in circumstances where two big strike waves (1969-74 and 1980-82) were still a very recent memory in the minds of working class militants, its architects had to rein in the militants with the capacity to wreck it through strikes, and the members of the AMWU and BWIU were at the top of that list.

Before going on, it is worth considering why the left wing trade union leaders were prepared to take on this responsibility. Answering this question also underpins my explanation for the developments in the years after the Accord. Trade union leaders occupy a contradictory role in the labour movement.[10] They are under pressure from the bosses with whom they negotiate and who value “partners” who can deliver “reasonable” outcomes that do not jeopardise their profits and who can ensure that any deal struck will stick with the rank and file membership. Outside the workplace or enterprise, union leaders are also subjected to pressure to be “reasonable” from the courts, government ministers and the media who insist that business must make profits. The pressure ratchets up as capitalism ages and becomes more crisis-prone: there is less space for concessions by the employers.

The union leaders are also, however, under pressure from the rank and file members who join unions and go on strike in order to improve their wages, working conditions and treatment by supervisors, to defend their jobs and, sometimes, to make political demands on governments. Union leaders who fail to demonstrate any capacity to lead such fights may be shunned by members and replaced by more militant contenders for the leadership, or their unions may simply lose out to others that do demonstrate these fighting qualities. At times, the union leaders themselves, in order to buttress their bargaining power with recalcitrant employers, may try to galvanise rank and file workers for industrial action.

The job of union leaders is to manage these conflicting pressures which are rooted in their social position as a buffer between labour and capital. They are, as one author put it, the “managers of discontent”.[11]

But the union leaders do not merely compare the contrasting force of the pressure from above (the employers, state, media) and below (the members) and act in concordance with the stronger of the two. Ultimately, the full-time union official is a creation of capitalism; their role depends on the continued existence of wage labour. Under communism, where the sale of labour power has ended, there will be no union officials. Unlike the working class, therefore, they have no interest as a social layer in fighting to overthrow the capitalist system. Indeed, union leaders have repeatedly proven themselves to be the last line of defence for the capitalist order when all else has failed. Even short of revolution, which hardly impinges on their consciousness on a daily basis, an active, militant, rank and file membership means more work for them, puts them under more pressure, forces them to stand up more to the boss and, if they fail to do so, makes it much more likely they will be thrown out of office at the next union election. For a quiet life, they want as much as possible a union membership that is passive for the most part but which can occasionally be revved up for action when the bosses or a government minister has to be convinced of the need for some concession. Hence the appeal of arbitration for union leaders, in that it provides a perfect mechanism for directing class conflict away from the hurly-burly of strikes and lockouts and towards the serenity of the court room. In the former, they are subjected to the indignity of workers poking them in the chest wanting answers; in the latter, they reign supreme as the embodiment of the union’s collective will. Hence the appeal also of Labor governments as an avenue to pursue workers’ demands: quiet lobbying by union delegations in ministerial offices is less irksome and onerous than the hard work involved in an industrial fight.

Further, the union leaders enjoy various material benefits that go with their role. For those who used to work on the tools, taking a job in a union office is a definite social and economic advance, in terms of pay and conditions of work – apart from anything else, they are unlikely to suffer any serious injury at work. Their rates of remuneration, taking into account salary, superannuation, a union car and phone, travel allowances and the rest of it, are commonly double those of the average member, sometimes triple. And none of these are affected by any deals they strike. If they sign off on a deal to cut jobs or hold down pay, they do not face the dole queue or cuts to their living standards.[12] If they agree to reduce staffing or speed up work, they do not have to work any harder themselves. They are not workers but functionaries of the union. And if they rise through the ranks, they become figures of note, interviewed by the media, treated with respect by government officials and politicians. More rewards wait for those who do not make waves: the prospect of a position in parliament, appointment to the arbitration commission, the offer of an HR position at a big company, or a well-paid job in the public service. Very few full-time officials happily return to the workplace from such a position. If social being determines consciousness, as Marx famously argued, the pressures on trade union leaders towards conformism with the capitalist system are obvious. All these factors come together to cohere the union officialdom into a bureaucracy, a conservative social layer in the labour movement.

Two small qualifications can be made. First, the pressures towards conformism are usually felt more acutely by those higher in the union apparatus for the simple reason that they are more removed from rank and file pressure, and because they come under more pressure from the bosses, as their actions can have more impact on the profitability of particular companies or the fortunes of the “national economy”. Nonetheless, the difference between the national or branch secretary and the local organiser is not as marked as it once was: the fact that the latter are today mostly appointed rather than elected has lessened the pressure from members on this layer too. And there are plenty of organisers only too keen on an easy life for themselves and with an eye to a position in HR.

Second, the social role of the trade union leader does not mean that divisions between left and right in their ranks are irrelevant, as any comparison between the leadership of the Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (CFMEU) and Shop, Distributive and Allied Employees’ Association (SDA) will demonstrate. But nor is it determinative of their role in the last instance. The behaviour of all union officials, no matter how left their rhetoric, is shaped by their social function. And the history of Australian unionism is that it has been the left officials, with their greater credibility among the militants, who have the greatest capacity to save the capitalists’ skins. So it was with the Accord and the Hawke Labor government.

The left wing union leaders promoted the Accord on the basis that it was a step towards a planned economy and thus towards socialism. For those with a more limited ambition, it offered unions the ability to embrace a wider social agenda. By agreeing to wage indexation and “no further claims” (that is, a no strike commitment), the unions would, supposedly, be able to sit down with the government to discuss implementing reforms to boost the welfare state. Accord supporters argued that this would benefit the whole working class, not just those in the more militant unions who could push for higher wages by going on strike.[13]

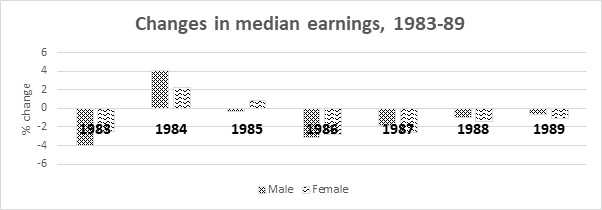

Regardless of the claims made for the Accord, it was a strategy that in practice drove the working class and union movement backwards. The obvious problem was that by agreeing to make no further claims for wage increases outside indexation, the union leaders allowed real wages to fall as full indexation was breached from the outset. By the end of the decade, median earnings had fallen by 7.1 percent, adjusted for inflation (Figure 1 – see Appendix). Not even Malcolm Fraser or, subsequently, John Howard, cut real wages like the Accord. And, far from helping to close the gender wage gap, female workers experienced an even larger wage cut (7.4 percent between 1983 and 1989) than men (6.8 percent). By holding back on strikes, waged workers went backwards across the board. The contrast with one group of predominantly female workers, the Victorian nurses, who went on strike in defiance of the Accord, is conspicuous. The nurses went out for seven weeks in 1986 after months of being given the run-around by the state Labor government. Even though they faced opposition and white-anting of their campaign by both the ACTU and Victorian Trades Hall and outright hostility from the minister for health, they prevailed in their fight for increased wages and a better career structure.[14]

The Hawke government did throw the unions one bone in its early years – Medicare – but even this was used as a justification not to fully index wages in the year of its introduction. The other “win” promoted by the Accord’s supporters, the introduction of industry superannuation, was likewise used as a justification not to fully index wages – and, at the same time, gifted governments then and since with a rationale not to boost the age pension.

Even more damaging than the wage cuts, however, was the harm the Accord did to the union movement. First, the unions became identified as organisations that fought not for improved living standards but for “national competitiveness”, and that meant profits came first. This was evident in their role promoting “industry restructuring” and “workplace reform” which involved thousands of redundancies across manufacturing industry.

The Accord destroyed those militant traditions that had survived the Fraser years and the 1982 recession. Some unions chose not to buckle under to the restrictions of the Accord – for example, the Food Preservers Union, the Furnishing Trades, the Builders Labourers and the Airline Pilots – but they were targeted for retribution by the ACTU which acted as the Hawke government’s industrial police force. Activists recall being at a BLF picket in Sydney during their battle against deregistration when BWIU officials relied on police to usher their members through the picket lines.[15] Not only did this break down traditions of honouring pickets – a question of basic solidarity – but it also meant their members had to walk up many flights of stairs because lifts operated by the BLF could not operate. So a condition established in previous disputes, that BWIU members could not be required to walk up numerous flights, was lost. Former union militants who had led strikes for big wage increases in earlier years were sucked into industry restructuring committees that drew them away from their fellow workers and turned them into apologists for the employers and the Labor government. Those who still wanted to strike for higher wages were reined in by their union officials.

At the end of the 1980s, centralised wage indexation gave way to the introduction of certified agreements allowing variations of award conditions, the two-tier wages system and award restructuring. The focus of the Accord now switched from straight wage cuts to destroying working conditions and union control on the job.

In 1991, the ACTU and Labor government joined forces to introduce enterprise bargaining, which had originally been promoted by the Business Council of Australia as a way of undermining the award system. Enterprise bargaining has proven to be a disaster for the union movement and working class. Its fundamental fault is that it is premised on undermining working class solidarity. The new principles adopted by the Industrial Relations Commission banned any return to the industry-wide campaigns of the type used in the 1960s and 1970s, which had lifted wages across the board. Henceforth every group of workers had to eke out the best result that they could. By splitting up the workforce into those able to push up wages through enterprise agreements and those who found it more difficult to do so, predominantly those working in small enterprises, enterprise bargaining led the unions to abandon the latter to the mercy of the Commission and its panel of economists responsible for determining the annual adjustment to the minimum wage. With a widening gap opening up between the two industrial instruments, agreements and awards, employers were given an incentive, growing larger over the years, to force workers off the former and back down to the latter, increasingly threadbare, award standard.

In 1993, the Keating government’s Industrial Relations Reform Act (IRRA) took the process of undermining the award system further. A new stream of non-union “enterprise flexibility agreements” was established. Although the ACTU disapproved, it refused to fight it. By now the union peak council had the enterprise bargaining bit between its teeth. The Accord Mk VII of 1993 stated:

The Accord partners support an approach which places the primary responsibility for industrial relations at the workplace level with a framework of minimum standards provided by awards of industrial tribunals. Such an approach is fostering workplace reform and building a new productive culture. The ACTU accepts and encourages the increased proliferation of enterprise bargaining.[16]

Much more damaging even than these changes was the string of anti-strike measures included in the IRRA.[17] Prior to the Act, there had never been a legal right to strike. The absence of a legal right to strike did not, however, inhibit Australian workers from striking: in the 1970s Australia had one of the highest strike rates in the Western world. Employers had the option to take unions to court for damages in tort for loss resulting from strikes, but very few did. In 1985 in a high profile case at Dollar Sweets in Melbourne, the owner, backed by conservative organisations and up and coming Liberal party lawyer Peter Costello, successfully used the court to pursue the union for damages. This was still, however, an exception.

The case of Dollar Sweets alerted the International Labour Organisation to the fact that Australian unions did not enjoy protection from tort actions and resulted in ILO censure of the government for failing to make provision for legally protected strikes. The Reform Act introduced a right for workers to take “protected action”, including strikes, for the first time. However, the Act surrounded this right with so many limitations and exceptions that in practice, workers were in a worse position than before.

It is worth spelling out the ways the Reform Act did this since it set up the basic framework unions have to battle with to this day. First, strikes or indeed any industrial action that took place outside a narrow window of negotiations called the “bargaining period” were unprotected. From the moment of signing an agreement until its expiry and the opening of negotiations for a new agreement, the union signatories were prevented from striking, no matter what the provocation from employers. Even once negotiations had been initiated for a new agreement, no industrial action could take place unless the unions had first attempted to negotiate a new agreement to the satisfaction of the Industrial Relations Commission (IRC). Strikes in pursuit of an industry-wide campaign were disallowed: industrial action was only protected if it was in pursuit of single enterprise agreements. And no industrial action was to take place unless the employer had first been given 72 hours’ notice.

The bargaining period during which action could be protected could be terminated by the IRC if it determined that the union was not bargaining in good faith or if the dispute “threatened to endanger the life, the personal safety or health, or the welfare, of the population or of part of it” or “to cause significant damage to the Australian economy or an important part of it”. Such an action to terminate the bargaining period could come about either on the Commission’s own initiative or on that of the employer or the Minister. Heavy fines, both for the individuals and the unions involved, were stipulated for those breaching the new Act, for example by striking outside the bargaining period in response to victimisation of a union delegate.

The significance of the Act was that for the first time since the penal powers had been rendered unenforceable by the general strike against the jailing of Tramways Union leader Clarrie O’Shea in 1969, the industrial courts were given the wherewithal to target unions for going on strike. Unlike the penal powers and unlike common law action against the unions, these powers were endorsed by all of the unions as part of their commitment to the new bargaining regime. The ACTU declared:

The Australian trade union movement has been at the forefront of workplace reform. We support the Industrial Relations Reform Act as being both well measured and socially responsible. [18]

Prior to the early 1990s employers had been hesitant to take on powerful unions for fear of the industrial backlash. Now, they were much more prepared to go on the offensive. With union coverage having fallen from 48 percent of the workforce in 1982 to 40 percent in 1990, with union combativity seriously undermined by years of industrial passivity, and with the old networks of union militants more or less gone, the employers seized their opportunity. In the iron ore industry and the coal mining industry, two former union strongholds, Rio Tinto and BHP set about trying to destroy the Australian Workers Union (AWU) and the Miners Federation, succeeding in the former and scoring some big wins in the latter.

The Kennett government took the fight to the union movement in Victoria on its election in 1992, abolishing state awards and replacing them with individual contracts. Here was an opportunity for the unions to fight back. The early signs were propitious: the Victorian Trades Hall Council called a one-day strike in November 1992 which brought out 150,000 onto the streets of Melbourne. But the momentum was squandered. Trades Hall declared a Christmas truce and by the time of the next day of action, in March 1993, the energy that had propelled people onto the streets had dissipated.

By 1996, when the Coalition under John Howard returned to federal office, union coverage was down to 31 percent, 17 points lower than when the Accord was signed. This catastrophic drop in union coverage, it is worth emphasising, took place under federal Labor governments.

If the Accord was a calamity for the working class it was, however, good for one layer within the union movement – the union bureaucracy. The Accord turned the union leaders into national political figures with easy access to senior ministers. They were appointed to numerous boards and committees to oversee industry restructuring. ACTU secretary Bill Kelty was appointed to the board of the Reserve Bank. National union leaders were in the media on a daily basis. They were sent on overseas “fact-finding” trips with politicians, public servants and employers to investigate ways to make Australian industry more competitive. There were the usual inducements of parliamentary positions – ACTU presidents Simon Crean and Martin Ferguson both ended up on the ALP front bench – while others were appointed to various government bodies and industrial tribunals.

The bureaucracy of the union movement grew more powerful in the Accord years because rank and file activism was virtually eliminated by the no-strike pledge and because the union leaders were promoted by the Hawke and Keating governments. But the decision by the union leaders to concentrate union membership into a small number of super unions through a process of mergers and amalgamations was another factor pushing power to the top. By 1993, just 11 unions encompassed two-thirds of all trade union members. The result was the creation of large organisations with hundreds of staff and substantial financial and property assets overseen by an ever more remote official apparatus. The resulting omnibus structures, with their memberships drawn from widely disparate occupations and industries, resulted in a further distancing of members from their unions: no longer did many unions appear to have any clear idea who they were for. The memberships were being stretched into ever wider elements within the working class but the campaigns that forged any sense of commonality were being broken down into ever smaller components of the membership through enterprise bargaining. The overall impact was to provide the union leaders with a bigger buffer from rank and file members, insulating them more effectively from pressure from below.

Since the Accord

Union decline and bureaucratisation went hand in hand in the Accord years. The problem for the union bureaucracy was that by the time the Howard government took office, the unions had become so hollowed-out that the incoming government felt confident to go on the offensive.[19] The attacks were immediate. The government’s first budget slashed thousands of public service jobs and cut funding for education and health.

Bill Kelty had said that if the Howard government attacked the unions, it would be met with fierce resistance. But when the challenge came, in the form of the Workplace Relations Act (WRA), the unions huffed and puffed but undertook no serious action. A combined union and community protest outside Parliament House in August 1996 got out of the control of the union leaders and what was meant to be a set-piece rally addressed by Labor leader Kim Beazley turned into an invasion of the lobby of Parliament House. The union leaders quickly disowned the protest and thereafter ensured that only token events were held to protest against the WRA, with the focus being instead on lobbying the Democrats, who held the balance of power in the Senate. The union response to the early attacks by the Howard government set the template for what was to become standard practice in the next couple of decades: to lobby parliamentarians, run public relations campaigns, and await the return of a Labor government to set things right.

Having passed its industrial laws, the Howard government now egged on the employers to step up their attacks on the unions. Chris Corrigan, CEO of Patrick Stevedores, took on the challenge over Easter 1998, sacking the company’s 1,400 wharfies and replacing them with scab labour. The union response was immediate. “Community assemblies” were set up at the entrance to Patrick’s operations around the country and quickly drew in hundreds, sometimes thousands of supporters from across the labour movement and beyond. In Melbourne, Sydney and Fremantle, these assemblies prevented the movement of containers from the docks, throttling Patrick’s operations.

The waterfront dispute was a big opportunity to mount national solidarity strikes in support of the sacked wharfies that could have transformed the industrial situation and landed a serious blow on the Howard government. But the Maritime Union of Australia (MUA) and ACTU leaders diverted the immense solidarity into a legal challenge in the courts. The community assemblies, which repeatedly demonstrated the potential to shut down the entire waterfront, were held back from doing so, in the name of “boxing clever”. The outcome of the waterfront dispute was a legal victory; the wharfies were reinstated and the MUA was restored at Patrick, but, in a story that was told repeatedly in the late 1990s and 2000s, the resulting negotiations over a new enterprise agreement saw the unions agree to dilution of conditions, including, most disastrously, the wholesale casualisation of wharf labour.

Over the following years, the employers and Howard government drove things further and further to the right, with more successful pushes to de-unionise industries and more gradual tightening of the industrial laws. Peetz argues that these measures constituted an “institutional break” in what had been a legal and political environment supportive of high levels of union coverage.[20] In 2005, the government introduced the Australian Building and Construction Commission (ABCC) as the culmination of a big campaign to demonise the CFMEU. A critical element of the ABCC has been its ability to initiate prosecutions of unions; no longer does the government have to try to push individual employers, sometimes reluctant to go into battle against the CFMEU, into an industrial confrontation.

The unions, by and large, refused to fight. The language of “boxing clever”, being industrially “smart”, “tactical” and running “long-run community campaigns” – all rationales not to go on strike but to pursue cases in the courts or election campaigns to toss out conservative governments – came to the fore. The strike rate fell further, and so too did union coverage.

The scene was set, therefore, for the introduction of the WorkChoices laws once the Howard government won a Senate majority at the 2004 federal election. These laws represented a dramatic escalation of the anti-union offensive. The union leaders understood that not to fight WorkChoices meant their further marginalisation in industrial and political life. And so in 2005, the peak labour councils launched the Your Rights at Work campaign which included a high court challenge, lobbying senators, a massive media campaign and four days of mass rallies over 18 months. Attendance at the rallies was enormous – with 550,000 attending protests across the country in November 2005 – and demonstrated, as had the MUA dispute in 1998, the potential to mobilise mass industrial opposition to employer and government attacks. But that was not the aim of the ACTU campaign, which funnelled popular opposition into a vote Labor campaign.

The slogan “Your Rights at Work Worth Fighting For” was changed to “Your Rights at Work Worth Voting For” at the last of the big national days of action in November 2006, and the next 12 months saw hostility to WorkChoices channelled into electoral campaigning. Six thousand unionists were involved in some form of electoral activity, more than two million leaflets were distributed, 40,000 people were door-knocked in a canvassing campaign and 5,000 volunteers handed out how to vote cards at 835 polling booths in 25 marginal seats on polling day in November 2007. The Howard government was defeated and the prime minister lost his seat thanks in no small part to the union campaign. Missing from the campaign, however, was any push to restore the right to strike or union rights more generally.

Union decline in the 1990s and 2000s was not inevitable. The battle against WorkChoices, along with the protests against the Kennett government in 1992-93 and the fight on the waterfront in 1998 provided union leaders with the opportunity to seriously push back, to confirm the relevance of trade unions and to regain the initiative against the bosses and governments. But, pulling back from the kind of action needed to score a decisive victory, the unions were incapable of checking the long term decline in membership and activist structures.

It was not the case that workers simply became uninterested in trade unionism in these years, as right wing critics argue. Public attitudes to trade unions remain supportive despite the best efforts of the right to delegitimise them, most recently the Abbott government’s Trade Union Royal Commission.[21] In an Essential poll conducted in 2015, 62 percent of all voters were of the opinion that unions are “important for Australian working people today”. Only 26 percent believed that Australia would be worse off with stronger unions, 45 percent better off.[22]

In the years that followed the defeat of the Howard government, the Rudd and Gillard governments scrapped some of the more punitive provisions of the WorkChoices laws, in particular Australian Workplace Agreements (statutory individual contracts), and reinstated an improved floor of conditions for enterprise agreements (the “better off overall test”) and a weak unfair dismissal provision. The ABCC was folded into the Fair Work Commission and maximum penalties cut by two-thirds. The Fair Work Act loosened rules over what could be bargained over, including contracting out and casual employment, and Howard-era greenfields agreements, which allowed employers to unilaterally set employment conditions on new sites, were amended.

Nonetheless, the anti-union clauses, and in particular the anti-strike clauses, were for the most part simply transferred across from WorkChoices to Fair Work. So, for example, the new Act includes the requirement to apply to the Fair Work Commission for a protected ballot action order and then to conduct a secret postal ballot prior to industrial action. It also included the requirement that at least 50 percent of the union’s members in the relevant area return a valid ballot, the continued ban on pattern (industry-wide) bargaining, the banning of political strikes, the deeming of all forms of unprotected industrial action as unlawful and injunctible and the obligation on the Commission to enforce mandatory orders in the case of such action, along with mandatory restrictions on industrial action which threaten “to endanger the life, the personal safety or health, or the welfare, of the population or of part of it; or to cause significant damage to the Australian economy or an important part of it”. This latter provision has proved extremely damaging to the unions. When unions at Qantas took very limited industrial action in 2011 to limit outsourcing and guarantee jobs for the maintenance crews, the Commission used this clause of Fair Work to terminate the bargaining period and impose a settlement which rejected all of the unions’ big claims. The result is that what should be a very powerful group of workers at the airports is now employed by a myriad of undercutting firms on multiple EBAs.

Other Fair Work restrictions included continuing restrictions on the right of entry for union officials and the prohibition of any closed shop or preference arrangements. Employers may be prevented from legally locking out their workforces unless the union has first initiated industrial action, but they face no other restrictions on their ability to do so, no matter how disproportionate their action might be. A provision for “award modernisation”, including four-yearly reviews of modern awards, was included in the Act, which in subsequent years has led to a stripping out or weakening of some long established provisions including, most damagingly, penalty rates.

Although welcomed by the ACTU at the time, the Fair Work laws are, as AMWU national industrial officer Don Sutherland has recently argued, “barely” better than WorkChoices and “very much in the same neoliberal ideological framework”. Fair Work is shot through with rules that reinforce employer prerogatives and undermine workers’ ability to organise collectively. Enterprise bargaining, in particular, Sutherland argues, is “rotten to the core”, based as it is on using competition between workers in different enterprises, and sometimes even the same enterprise, to break worker solidarity and encourage a race to the bottom.[23]

Union strategies today

The result of developments over the past three decades is that trade unions today face an industrial relations set-up in which the bosses, backed by the Fair Work Commission, courts and governments, have been emboldened to attack unions on every front. This involves removing the remaining institutional props that have kept the surviving unions alive, or in some cases, retaining the form of a union onsite but removing what is left of its power. Employers are aiming to eliminate what remains of the conditions won by industrial militancy and on the job organising in the union movement’s remaining redoubts. Workers in these redoubts will be able to hang on to only what they are able to fight for and no more. In many situations, this will result in the stripping out of vital conditions that have been tolerated by employers in times past.

One employer tactic is to use labour hire companies to set up enterprise agreements with one or two workers and then to outsource parts of their workforce to these labour hire operations on far inferior wages and conditions. This was what Carlton and United Breweries (CUB) planned for its maintenance workforce at its Melbourne brewery when it set up a labour hire company in 2014 and then sought to move its workers over to the new contractor two years later.

The tactic was given the blessing of the courts in 2015 when the Federal Court upheld an enterprise agreement negotiated and voted on by only three John Holland employees at the Perth Children’s Hospital project, which the company then used to set terms and conditions for much wider groups of employees who had had no say in the making of the agreement. The John Holland precedent was then used by Esso to do the same in 2016-17 with the outsourcing by contractor UGL of maintenance workers on the Bass Strait gas project to its own shelf company resulting in 30 percent wage cuts and casualisation.[24]

Another tactic has been for employers to apply to the Fair Work Commission to simply terminate expired enterprise agreements. This is a provision of the Fair Work laws, carried over from WorkChoices, but had been rarely used until 2015 when, breaking precedent, the full bench of the Fair Work Commission terminated 12 expired EBAs at Aurizon, Australia’s largest freight rail company. This allowed the employer to roll the Aurizon workforce onto a much inferior agreement. The full bench approved termination of the agreements under s226 of the Fair Work Act, on the grounds that there was no public interest not to and that the changes proposed by the company under the new agreement were not “undesirable or unnecessary, oppressive on employees or inappropriate”.

The Aurizon decision gave a green light to other employers to apply to terminate expired agreements on the basis that the existing conditions in what are sometimes called “legacy agreements” from the days of public ownership, or where unions had otherwise managed to hold the line, were now far in excess of what has become the much inferior industry standard where conditions have been given up by weak or non-existent unions through rounds of concessionary bargaining. In the 1960s, metal trades unions leveraged the good wages and conditions in the well organised workplaces to win breakthroughs in the poorly organised shops through the award system. The employers are now using this method in reverse, with the bad driving out the good. This was the explicit rationale for Glencore’s lockout of its workforce at its Oaky Creek mine in Central Queensland in June 2017 – to drag down wages and conditions to the level prevailing at the company’s other mines.

Once an existing agreement is terminated, the bosses then have a free hand to threaten workers with being forced back to award standards. Examples in 2016-17 include Griffin Coal in Collie, WA, the Loy Yang power station in Victoria’s Latrobe Valley, Murdoch University in Perth, the NRG power station in Gladstone, the Nyrstar zinc smelter outside Hobart and the Streets ice-cream factory in Minto. In the case of Griffin Coal, maintenance workers lost between $24,000 and $29,000 a year when they were put back onto the award. Even where the employer only threatens but does not proceed to terminate the enterprise agreement, as at Coates Hire or Fletcher Insulation, these threats combined with lockout are a powerful factor forcing concessions in any new agreement.

Workers and unions are under siege. The slashing of penalty rates by the Fair Work Commission in July 2017 is the most drastic cut to worker entitlements since the 1930s. The Turnbull government’s reintroduction of the ABCC, together with its Building and Construction Code of Conduct, is being used to drive effective trade unionism from the construction sites. The franchise business model has encouraged employers in retail and hospitality to cheat workers of their wages and conditions.

The union response to these latest attacks has varied. In some cases, there has been dogged resistance, with workers maintaining protest lines during lockouts lasting months. For example, unions maintained a presence for six months outside CUB in 2016 after 55 ETU members were sacked for refusing to sign an inferior employment agreement. There are even flickers of resistance in regional towns, as at the Myrtleford pulp mill in country Victoria in 2017, where workers had to face not just the scabs but hostility from many in the town.

But such resistance is the exception rather than the rule; union timidity has been more obvious. At the extreme end of the spectrum is the SDA, for many years the country’s largest union, which has worked hand in glove with the bosses to undermine wages and conditions. The SDA has tens of thousands of members in the big retail and fast food chains, where it maintains a presence on the basis of sweetheart deals with the employers. All told, the sub-standard enterprise agreements the union has signed in recent years have stripped wages from 250,000 workers, saving big business more than $300 million a year.[25] The SDA has done nothing about the exploitation of migrant workers and international students ripped off by 7-Eleven franchisees, one of the country’s largest retail chains. The union was either ignorant of the conditions at 7-Eleven, or was aware of them and took no steps to challenge them. Neither reflects any credit on the union.

The SDA may be held in contempt by many unions, but it is significant that only one, the Meatworkers, publicly opposed the deal it struck at Coles. The ACTU leadership, charged with overseeing the general interests of the union movement, brushed off criticisms of the SDA, arguing that cashing out penalty rates was a common tactic in enterprise bargaining.[26] Likewise Labor leader Bill Shorten. That the SDA is the ALP’s largest donor and constitutes a significant factional force ensures that Labor leaders usually treat it with kid gloves. Had it not been for the work of a couple of Age journalists, an organiser at the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) and a small number of SDA members, Coles’ deal with the SDA would have gone unchallenged.

Like the SDA, the Australian Workers Union also has a history of signing off on cut-price agreements that undercut awards and industry standards in return for membership coverage. It has long established itself as the union favoured by employers wanting to reduce conditions negotiated by the CFMEU and MUA.

But the problem does not just lie with the most craven union leaders. Their supine behaviour is exactly what one would expect. The real problem is that even in those sectors where the unions retain the capacity to land a few blows on the bosses, the fight has been half-hearted. Despite the fact that the country has not experienced a recession for more than a quarter of a century, wage increases negotiated through enterprise agreements have fallen year after year to their lowest level ever. In the public services, where unions still retain a presence, the usual pattern during enterprise bargaining negotiations is for the union leadership to call one or two state or national stoppages followed by a series of partial actions, department by department or agency by agency, that serve only to fritter away the initial momentum and solidarity. The agreements that have subsequently been signed usually feature a very modest pay rise and very often come at the expense of conditions like permanency or limits on outsourcing. It’s been a similar story in higher education. In one of the NTEU’s few strongholds, Sydney University, a very successful enterprise bargaining campaign, including a one-day strike that completely shut down the university, was ended prematurely in September 2017 as the state leadership hurried to settle with the management, abandoning some of the key claims in the process.

The failure of many unions to resist the employer offensive is also evident when it comes to redundancies. In the vehicle industry the AMWU leadership could only issue statements of “regret” when in 2013 the big car manufacturers announced their plans to shut down most of their operations in Australia. Thousands of unionised jobs went with barely a whimper. In the steel industry, the AWU, both at BlueScope at Port Kembla and Arrium at Whyalla, refused to fight mass sackings but rather accepted major losses to jobs, pay and conditions. In the maritime industry, the MUA did not take one hour of industrial action to prevent Alcoa and Rio Tinto subsidiary Pacific Aluminium from replacing Australian crews with foreign crews on much lower wages on their bulk cargo ships MV Portland and CSL Melbourne in the summer of 2016.[27]

In the steel and vehicle industries the unions faced a tough situation – it has been many years since any union has successfully fought for jobs when the employer threatened to shut the company down. But in other cases, there is no such excuse. When the Newman LNP government announced 14,000 sackings in the Queensland public sector in 2012, the biggest job cuts in the state’s history, the public service union Together had every opportunity to strike in defence of jobs – the state government was not just going to shut down. And there was no legal impediment to the union doing so: the previous enterprise agreement covering Together members had expired and so protected action was on the cards. The union leadership balloted members for action and received strong endorsement. Delegates attending special meetings of the Queensland Council of Unions voted for a state-wide stoppage in September 2012. However, after the QCU held a rally which attracted a large crowd of 10,000 in Brisbane, neither the QCU nor Together organised any further industrial action and the government was able to force through the redundancies without opposition

One of the most damaging developments in the union movement over recent decades has been the erosion of the basic principle “touch one, touch all”, even in what are otherwise admirable examples of resistance to employer attacks. During the CUB dispute in Melbourne, unions brought hundreds of workers to the gates of the brewery on several occasions to demand the reinstatement of the CUB workers. The unions also launched a nationwide boycott of CUB beer. Eventually these tactics were successful and the company reinstated the workers. But throughout the course of the dispute, hundreds of workers, members of United Voice, continued to work at the Abbotsford brewery, as did union members at the company’s other big brewery in Yatala in Brisbane. A dispute that could have been won in a matter of weeks, had unions organised to shut down CUB operations, took many months.

The strategy that has come to dominate the union movement in the past decade is electoralism, specifically, campaigning to get the ALP elected, or re-elected.

The idea that workers should put their trust in Labor and vote them into office is by no means new. The unions founded the Labor party and “the two wings of the labour movement”, as they are described by reformists, have worked closely together for more than a century, despite periodic disputes. Each “wing” reproduces the division of labour that is central to the reformist project: the unions are held responsible for the industrial interests of the working class, the Labor party its political needs. This artificial separation of industrial and political demands works nicely both for the union and parliamentary leaders alike. It dilutes the radical potential of each – the existence of Labor, whether in government or in opposition, is used to damp down demands for greater militancy (“Don’t rock the boat, it will cost Labor votes”; “Just wait until Labor is in power, then we can get our grievance resolved”). The ALP also provides the union bureaucracy access to ministerial offices when the party is in government and a potential career option in parliament or well-paid positions that the party has the power to award – on commissions and statutory bodies of various kinds.

But for several decades this cosy arrangement was challenged by another tradition – a willingness by workers to fight for wages and conditions regardless of who was in government. Labor governments came and went, but it was fighting on the job that delivered the victories or pressured governments or industrial tribunals to introduce the reforms that workers were demanding. The battles for shorter working hours or paid annual leave in the 1940s were classic cases of this dynamic. The militant unionists won shorter hours through strikes, and governments and tribunals then generalised them through legislation and awards.

The problem today is that the militants who organised these strikes and who provided the impetus towards militancy were squashed by the Accord. The union movement is now firmly in the hands of the union bureaucracy and their strategies prevail. With unions unwilling to fight industrially, electoralism is the alternative that naturally comes to dominate as unions have been increasingly turned into appendages of the ALP.

The Your Rights at Work campaign campaign against the Howard government in 2007 served as the template which has been adhered to closely in subsequent state and federal elections. In the 2014 Victorian state election, for example, volunteers organised by Trades Hall knocked on 93,000 doors across six marginal seats and made 120,000 phone calls to potential voters.[28] The Napthine Liberal government fell. Unions in Queensland followed the pattern in the 2015 state election, campaigning in 16 marginal seats. The Newman government fell, losing 15 of the targeted seats. The unions were not successful at the NSW state election in 2015 when the NSW Labor Council failed to dislodge the Liberal incumbents.

One indication of the dominance of electoralism in the unions today is the sheer time, money and staff deployed. At the 2016 federal election, the unions contributed $14 million and allocated 24 paid organisers to the ACTU’s “Building a Better Future” campaign. The campaign targeted 22 swing seats. Over the course of 12 months, more than 16,000 volunteers played some role; these volunteers ran 80 door-knocks, handed out 1 million replica Medicare cards and “had conversations” with 46,102 union members to convince them to put the Liberals last.[29] At the 2017 WA state election, the MUA alone organised 200 members and supporters to staff polling booths around the state. Never do unions mobilise the same resources for any industrial campaign. There are cases of some unions pushing to break into new territory, as with the National Union of Workers’ (NUW) organising drive among agricultural workers, but these are small and the exception.

The unions now claim to be in “permanent campaign mode”. But this simply means permanent electoralism: no matter how remote the next election, the resources of the union, other than basic industrial representation, are devoted to electioneering. And so, just months after the Turnbull government narrowly won the July 2016 federal election, the unions began to prepare for the next. The ACTU official responsible for the 2016 campaign, assistant secretary Sally McManus, was hoisted into the position of ACTU secretary to reprise her role.

Electoralism has become the default union strategy and has pushed serious industrial campaigning further to one side. When Queensland unions marched in Brisbane in 2012 against the Newman government’s mass sackings, just six months after the election, the chant was “We’ll be sacking Campbell Newman in three years”. After this one mass action, the unions devoted the resources that could have been given over to organising industrial resistance on the job to electoral campaigning for the ALP.

The penalty rates campaign illustrates the problems with the electoral focus. The attacks on penalty rates were widely opposed as soon as they were first flagged in 2014. There was a general understanding in the union movement that those workers identified for the cuts had been selected because they were poorly organised and that, if the government and Commission met no opposition, they would then proceed to the more strongly organised workers – firefighters, nurses and so on. The cuts to penalty rates were something that were both a threat to Australian workers and could have been used to rally the whole union movement in opposition. The lead would have to come from the big battalions – certainly if it had been left to the SDA and United Voice there was little chance that the cuts could have been stopped since both unions have extremely limited industrial strength after years of neglect. Unfortunately, that lead was not forthcoming.

Rather, the unions looked for an electoral solution: only a Labor government could save penalty rates. This despite the fact that Labor leader Bill Shorten for many months urged the unions simply to accept whatever the Fair Work Commission handed down.

Following the 2016 federal election, the onus in the campaign mostly fell back on the shoulders of United Voice. The union started from a very weak base. But rather than use the issue as an opportunity to mount a serious campaign to target hospitality workers where they are concentrated in big numbers, United Voice organised a series of Sunday speak-outs, comprising mostly union staff and ALP branch members, outside suburban sports clubs. The idea was to put pressure on the club managers to refuse to implement the cuts. The clubs targeted were chosen on the basis that they were in marginal seats and the main game was to generate media coverage and a bigger pool of election canvassers.

The CFMEU did call rallies in the capital cities in the first half of 2017 against the ABCC, to which they added the demand to halt the cuts to penalty rates. However, none of the unions most directly affected by the cuts sent anything more than a token presence of a few union officials, at best. Other than building the local apparatus for marginal seats campaigning, the only other avenue pursued by United Voice was a legal challenge to the cuts on the eve of their introduction in mid-2017.

An obvious defence of the electoral turn by the unions is that Labor in office can deliver things for the unions that their own industrial power cannot. The unions might point to Labor’s repeal of WorkChoices and the Gillard government’s commitment of several billion dollars to fund equal pay in the community services sector. The Nurses Union for its part secured $1.2 billion from the Gillard government to fund higher wages in aged care. The Transport Workers Union (TWU) won a new “safe rates” tribunal with the power to set pay rates for truck drivers, while United Voice won $300 million for childcare workers under the Big Steps campaign. And today, union pressure has forced the ALP to shift its position on penalty rates; Labor now promises to legislate to restore penalty rates if it wins office. The ALP is also considering changing the Fair Work laws to make it more difficult for employers to apply to terminate expired enterprise agreement.

At state level, unions have found the industrial relations climate more congenial under the Andrews and Palaszczuk Labor governments than they did under their conservative predecessors. The Queensland Labor government, for example, passed new laws to regulate labour hire companies and has tabled industrial manslaughter legislation. None of these gains involved anything more than token industrial action on the part of the unions; mostly they were the result of a few rallies, a social media campaign and representations to the relevant minister.

If an incoming federal Labor government were to “change the rules” significantly, as the ACTU is now lobbying for, this would be welcome. Changes to make it easier for union organisers to gain entry to work sites; reducing some of the onerous restrictions on the right to strike; broadening the options for multi-enterprise agreements (“pattern bargaining”) would all improve the unions’ bargaining position. The union leaders certainly would welcome any limit on the right of employers to apply to terminate expired enterprise agreements because such a step threatens them with industrial irrelevance unless they demonstrate the capacity to push back.

There are problems, however with the strategy of awaiting a Labor government. First, many years can pass before Labor is actually elected. The ACTU decision not to challenge WorkChoices industrially gave the employers two years to introduce substandard contracts before Howard was defeated in 2007. Then there is the wait until an ALP government actually repeals anti-union laws. It was only in 2011, for example, more than three years after Labor was elected to office, that the Fair Work Act took effect, and dodgy WorkChoices contracts lingered on well beyond even that date. The ABCC was actually operational for longer under the Rudd and Gillard governments than it was under Howard. With fixed four-year terms now the norm for state governments and the prospect of such for federal government, workers can lose a lot of industrial rights before Labor is ever elected, especially if it fails at the first attempt.

Second, the ALP is by no means obliged to meet union demands. The Gillard government may have made life a little easier for some unions, but, when spread over big workforces, the funding packages for pay increases are not as generous as they may first appear. Given Shorten’s hostile response to McManus’ suggestion that unions have the right to break “unjust laws”, and indeed his own history both as architect of the Fair Work laws and as AWU national secretary, it would be foolish to expect a Shorten-led government to go far in relaxing the many restrictions on strikes, still less to stand idly by in the event of a real industrial fightback. Nor can it be expected that the Senate will be favourably disposed to any laws to grant unions more rights.

There is discussion in Labor circles around making it easier for unions to refer intractable disputes to the Fair Work Commission but this does nothing to boost union power. It may appeal to union leaders for the reasons discussed earlier – it puts them back in the frame – but if workers are not in a strong bargaining position, they can expect little joy from the tribunal. Likewise, while industrial manslaughter legislation and restoring penalty rates might improve safety on the job or working class living standards, they do nothing to rebuild the capacity of unions to fight for workers’ rights, the key ingredient. More than this, the focus on having Labor elected actually cuts against this project. As Tim Lyons, former ACTU assistant secretary, said of the union focus on election campaigning after he left office:

The union becomes not something about your work and your life, but an organisation that periodically tells you how to vote. Compounding this, the message is that it’s voting that is important, not joining a collective that has its own power. There is no future for trade unionism if people experience it as internet memes and random-issue phone calling and door-knocking about how every election is very likely the end of the world. At best this is palliative care for the union movement. [30]

Without building strength in the workplaces, the unions are simply at the mercy of Labor governments. And what Labor gives, it (or its conservative successor) can easily take away. That is exactly what happened when the Abbott government was elected in 2013: many of the union movement’s gains under the Gillard government, for example the Safe Rates tribunal, were simply eliminated at the stroke of a pen. Because the unions had not built the fighting capacity of workers, the government had little trouble wiping out the reforms.

But pointing out these problems is unlikely to shift the union leaders from their dependence on the ALP. It’s not just that many are increasingly anxious as they see their membership rolls decrease by the year and look to the election of Labor to save them from extinction. It’s not just that they see political lobbying as preferable to the hard work (and risk) involved in organising industrial campaigns. It’s not even that many are angling for parliamentary positions and that wheeling and dealing in the factional world of the party is a major obsession of the union bureaucracy. The main factor that draws the union leaders close to the Labor parliamentarians is that they remain deeply committed to the social democratic project of managing capitalism together. Many of them look longingly back at the Accord, when they were trusted partners of Labor ministers and employers. Ged Kearney argues that the Accord was “a highpoint of the political and industrial wings of the labour movement linked informally and formally in the national interest to deliver economic stability and historic reforms”.[31] Former ACTU secretary Dave Oliver was similarly enthusiastic:

In the past, a collaborative approach between government, employers and unions streamlined industrial awards, markedly increased production standards, ensured workplace safety, rationalised subsidies and tariffs and generally brought Australia kicking and screaming into the modern economic world. Collaboration between industry, unions and government enabled us to lay the foundations on which we built the economic success of the decades since.[32]

Doing deals with the ALP is part of the union bureaucracy’s DNA. This suggests that even if a future Labor government were to significantly relax restrictions on the right to strike, union leaders will not be in any hurry to make use of it.

Union decline and, in some cases, the cost of ever-rising legal bills and fines, is putting some unions at risk of collapse and this is encouraging union leaders to pursue amalgamations. Subject to membership ballots, and providing it is not barred by federal legislation, the CFMEU (125,000 members) will merge in 2018 with two unions which have seen dramatic drops in their national memberships over recent decades, the MUA (12,000) and the Textile, Clothing and Footwear Union (3,500). The AMWU, haemorrhaging members, is in discussions to amalgamate with United Voice and the National Union of Workers.

But amalgamations did nothing to revive the union movement during the last big round of mergers in the late 1980s and early 1990s, and there is no reason to believe it will be any different today. The leaders of the amalgamated unions may wield more power in factional battles inside the ALP but the mergers will not halt decline. Indeed, to the extent that some mergers will only introduce undemocratic governing structures in unions with more democratic traditions, they will only further alienate members and make it more difficult to revive.

Another indication of desperation in the ranks of the union leaders is the consideration that some are giving to even more dramatic shake-ups, including abandoning any notion that they should be primarily collective organisations of members on the job organising to defend wages and conditions. In the Brave New World that some envisage, unions should become professionally-run service providers selling packages of industrial, legal and consumer services to clients. In 2015, former ACTU president Greg Combet and Andrew Whittaker, a management consultant, produced a report for the Australian Manufacturing Workers Union. The union, they noted, was a long way from the heyday of the metal trades unions in the 1960s and 1970s and not just in membership. The internal culture of the union was toxic. The amalgamation of the old metalworkers, food preservers, vehicle builders and print workers unions into the omnibus AMWU in the late 1980s had created a dysfunctional structure, and there was a “pervasive sense of frustration, suspicion of colleagues and a conviction that change within the union was a forlorn task”. [33] Combet and Whittaker’s “solution” was for the AMWU to reposition itself as a service provider offering existing and potential new members enticing “value propositions” involving various combinations of “products” and “services”.[34] Elections for organisers would be eliminated and power centralised in the national office. “Digital-based communications” between members and union staff would replace face to face contact with organisers attached to particular sectors or companies.

Combet and Whittaker’s report was in line with thinking as it was evolving in the senior ranks of other unions. In February 2016, a special conference of union leaders, convened to address the dire state of the union movement, considered a report by Chris Walton and Erik Locke. Their report recommended introducing a “cafeteria approach” to union membership, by which workers might select and purchase subscriptions to individual services provided by unions, what they call a “ladder of engagement”, just like pay TV subscriptions.[35] On the lowest rung, workers could become a supporter just to get on a centralised database. They could then pay one or two dollars a week and have access to online support. They could pay more, in the order of $7 a week, and be provided with information about legal rights, industry campaigns, career development and financial planning but with no actual support of the union on the job. Or workers could be a full union member on the current lines. Applicants would simply need to call a centralised call centre in order to purchase one of these options. Like most such documents in recent years, Walton and Locke’s report is stuffed with the language of business consultancy, with its references to “the change process”, outsourcing “backend services” to reduce administrative costs, the need for unions to “calibrate your offer and services” for each target market, to conduct research on the union “brand” and ensure “alignment to core purpose”, etc.

The ACTU special conference in early 2016 established a series of “Innovation and Growth” taskforces and the ACTU executive set aside a kitty of $1 million for unions to experiment with ways to improve their operations. There was much discussion in these task forces about visions, value propositions, capacity building and the like, but missing was any discussion of militancy or strikes.[36] Organisations as diverse as Greenpeace, Lock the Gate, the Hillsong Church, Mamamia, the NRL, Google Hangouts and LinkedIn, were held up as organisations from which the unions could learn useful lessons on how to recruit and engage members.

It is unclear how far unions are willing to go down this road. Some have already moved. In 2016, the Media, Entertainment and Arts Alliance replaced the elected federal secretary’s position with a CEO appointed by a board of management, and introduced a new category of “associate membership”.[37] But if others follow, this would be a major retreat for the labour movement, exacerbating the problem of membership withdrawal. Subscriber-based service delivery organisations run by managers and emptied of any notion that the members are the union and that union power ultimately rests on workers’ capacity to fight the boss at the workplace would turn them into hollow shells. The removal of elections for senior positions and the creation of new categories of quasi-members without voting rights makes a mockery of union democracy. In such circumstances, the incidents of corruption by senior union figures identified by the media in recent years and by the Trade Union Royal Commission would only multiply.

Another development in the union movement that only pushes the unions more to the right is the increasing entanglement of national union leaders in the superannuation industry. The funds under management in industry super funds have ballooned since compulsory superannuation was introduced by the Keating government in 1991. Union leaders are now jointly responsible with employer representatives for more than $500 billion invested in 41 industry superannuation funds, equivalent to nearly one-third of GDP.[38] The biggest fund, Australian Super, has $100 billion under management.

The entrenchment of trade unions in a system of industry super funds has damaging consequences. First, it gives them a stake in what is a fundamentally regressive private pensions system. It structurally disadvantages women unionists who take time out of the paid workforce, thereby rendering them even more financially dependent on male partners, or condemned to poverty in retirement. It funnels money to financial institutions that receive mandates from the funds to manage investments. And, with highly concessional tax treatment of super, more of the national budget is channelled to those with the biggest balances, the well-off. The system ensures that the workers’ access to a financially secure retirement is increasingly dependent upon fluctuations in financial markets and not their rights as citizens. Unions should be fighting for increases to the state pension so that it provides a living income for all retirees, male and female, paid for from progressive taxation. But with unions tied up in industry superannuation, their role as advocates of the state pension is significantly compromised.

Membership on the boards of Australia’s largest financial enterprises pushes union leaders into the role of capitalists, alongside their traditional role of brokers of labour power. They are now responsible for individual investments worth tens of millions of dollars. Union appointees to super funds claim that the industry can be used to develop the Australian economy. Thus Oliver told a conference of superannuation industry representatives in 2016 of the “nation-building” role of superannuation, its role in preventing Australia slipping into recession during the global financial crisis, and its contribution to “building a new, stronger economy into the future”.[39] But the main contribution industry superannuation has made to developing “a new stronger economy” is to fund privatisation of public assets. Key assets on Australian Super’s books include Port Botany, NSW’s major container-handling facility, Port Kembla, Australia’s largest vehicle import facility and a major export facility for coal and other bulk products, Ausgrid, the lessee for NSW electricity transmission operations, and Queensland Motorways. All of them were once state assets.[40] As board members of Australian Super and other big industry funds with investments in these businesses, union representatives have an interest in further privatisation and opposition to any progressive renationalisation of those enterprises.

Union representatives on the boards of superannuation funds are now joint partners in the management of these former state assets. Oliver, AMWU national secretary Paul Bastian and his counterpart at the AWU, Dave Walton, are all board members of Australian Super and are responsible for boosting returns on the fund’s investment in Ausgrid, while Greg Combet plays the same role for industry fund-owned global fund manager IFM Investors. This puts them in an antagonistic role to the company’s workforce. As ETU NSW branch secretary Dave McKinley commented when Ausgrid outsourced jobs and shut down call centres in 2017: “What is most extraordinary is that these attacks on working people are being perpetrated by a company majority-owned by industry super funds”.[41]

As board members of big investment companies, union representatives are drawn closer into hobnobbing with capitalists. Appointees of the construction unions debate the investments of CBUS with the head of the Master Builders’ Association. Appointees of the manufacturing unions discuss the financial affairs of Australian Super with representatives of the Australian Industry Group. The result is what Oliver calls “collegiate and collaborative structures” between union leaders, private capitalists and former politicians.[42] The links with the capitalists continue once they quit the union movement. Garry Weaven, a union pioneer of industry super and former ACTU assistant secretary, is chair of IFM Investors, where he is joined by Combet as deputy chair. For all the scare stories in the right wing media about union corruption in super funds, much more concerning is the insistent right wing pressure that bears down on union board representatives.

Why strikes?

Nothing that the unions have done over the past two decades has halted their relentless decline. Avoiding extinction outside a few small pockets of the workforce requires a radical change of direction. I will argue in what remains of this article that this change of direction must involve returning to the strike as the main weapon of the labour movement.

Australia’s industrial history is replete with examples of strikes winning improvements for the working class. Shorter working hours legislation by the NSW state government, which cut the working week from 48 hours to 44 hours and then to 40 hours, was the result of big waves of strikes in the late 1940s and again in the early 1960s – and by the simple expedient of workers knocking off work having done the target number of hours. Likewise, the progressive extensions of paid recreation leave from one week to four.