Gulf War: Lessons of the movement

Playback speed:

The revival of mass mobilisation

The nationwide explosion of protests triggered by the US offensive on January 17 claimed an early victim. The wave of struggle decisively rebuffed the most depressing element of 1980s “common sense” – that ordinary people have no interest in politics and that militancy is dead. In every capital city, and in other large centres, anti-war activity sprang up overnight. More than 100,000 marched, groups leafleted shopping centres, flags were burned, students flour-bombed the army reserve, anti-war groups were established in workplaces, high school students held teach-ins.[1]

It confirmed what revolutionaries had been arguing in the face of apparently unchallengeable evidence – that capitalism would once again force a new generation into struggle. People clearly were prepared to get involved in politics. A small minority of workers did gain the confidence to be politically active in the workplace. Students, even though the war took place largely in holiday time, organised angry protests.

The old arguments that held sway, for instance in the student campaign against Labor’s graduate tax, that demos were a pointless hangover of the 1960s, that militancy had to be curbed to get good media coverage, were shaken. Many people discovered in practice that despite the media’s hostility, militancy enthused new layers of activists. That the sense of power that flowed from even the smallest march built the movement.

Of course, not everyone agreed. Many long-term activists, worn down by holding together remnants of earlier movements, were cautious or even hostile to mass mobilisations. Senator Jo Vallentine even complained that Palm Sunday marches once a year were too much. In Melbourne, the majority of the steering committee of the Network for Peace in the Middle East voted to leave three weeks between major demonstrations because they thought too many mobilisations would exhaust the movement. This was a mistake, because each activity built support for the next. In the middle of a political crisis three weeks could seem like six months.

The lessons of the movement also include the importance of clear political ideas. Opposition to the war was a good starting point, but the movement had to be able to convince new people to join in, and individual activists had to be confident they could argue convincingly against the warmongers amidst a crisis which threw up no end of political problems. Should the movement condemn equally Iraq and the US? Were sanctions the alternative to war? Could the United Nations defuse the situation? Should the peace movement call for a ceasefire and a negotiated settlement?

This article examines the strategic and tactical issues with which the movement had to tussle; the political issues with which activists had to deal; and the relationship between socialists and the movement.

The movement is born

Given the decline of most of the organised left and social movements, the response to the US mobilisation in August 1990 was better than anyone could have forecast. In Melbourne, 250 responded to a call by Rainbow Alliance to picket Labor minister John Button at nine on a Saturday morning. This was followed a week later with a demonstration of 400, which became controversial because a group of anarchists burned the US, Iraqi and Australian flags, attracting outrage from the media and pro-war politicians.

In Sydney, there was a small picket at the wharves as the first Australian warship left. A meeting of 35 people from peace, environmental and Arab-Australian groups and the left set up the Bring The Frigates Home Coalition and planned a demonstration for September 1. The theme was “Bring the Frigates Home – No Gulf War” and the targets were the US consulate and the Australian Defence Department.

In Brisbane, the Gulf Action Coalition was formed from a meeting of 200 called by People for Nuclear Disarmament (PND) and organised several rallies that attracted between 200 and 300. A “welfare not warfare” picket confronted Senator Richardson at Queensland University in October. In Canberra the ISO took the initiative, calling a public meeting which led to the establishment of the Bring the Ships Home Coalition.

As with Vietnam, mobilisation against the war was modest but immediate. There were a number of factors that contributed to this, not least the experience of the Vietnam movement itself. Although many involved in that struggle had dropped out of organised activity or had moved into mainstream Labor Party careers, a small but important minority had remained linked to extra-parliamentary politics, resurfacing in mass campaigns like the Movement Against Uranium Mining (MAUM) and later PND. That sense of continuity was obvious on the initial mobilisations in the winter of 1990. In Melbourne and Sydney, former Vietnam-era activists were among the speakers and made up a proportion of the crowd.

Just as importantly, among those too young to have participated against the Vietnam War, the anti-war tradition had a resonance. The concept of the “teach-in” made sense to many new activists; the “Hell no, we won’t go, we won’t die for Texaco” slogans were chanted unselfconsciously; it was possible to argue that building workplace anti-war groups was a step towards calling moratoriums.

The experience of mass marches for disarmament in the early 1980s also contributed to the ease with which the movement got off the ground. The idea of peace, however fuzzy, had a continued attraction for young people long after the movement itself collapsed. The peace symbol survived as a political statement. In small numbers at first, but in their thousands once the shooting war broke out, young people swelled the ranks of the movement.

There was a further reason why the demonstrations were bigger, and built more quickly – the experience of eight years of Labor in office. A combination of wage cuts under the Accord, deteriorating social services, and Labor’s support for Western imperialism – for example uranium exports and MX missile tests – meant a significant minority was cynical about Canberra’s support for the war. The cynicism grew when Hawke sent the frigates without bothering to consult parliament or even Cabinet.

However, the experience of life under Labor also set up barriers to translating disenchantment into action. The Accord had undermined the level of combativity, in the workplace and beyond. Political traditions had been weakened by years of “responsible co-operation with management”. The shop stewards’ committee at Williamstown dockyards in Melbourne, for instance, which had been important in the campaign against uranium mining, had been wrecked by award restructuring.

A further problem was that whereas the recession in the US started after the Gulf build-up had begun, and therefore seemed to be linked to it, in Australia recession predated the Gulf crisis. Workers preoccupied with the threat of unemployment might lack the enthusiasm and confidence required to take action against the war.

Although the initial wave of opposition to the war drive was small, support for war was at best lukewarm. When RAN ships weighed anchor in Geelong only the protesters and the sailors’ families were there to see them off. On radio phone-in shows, support and opposition to the build-up to war ran neck and neck in the first few months. In later opinion polls, strong opposition to the war reached at least 11 percent at one stage, more than those moderately against.

Strikes continued without any attempt by the media or the tight to tar strikers with being unpatriotic. Nearly 1,500 wharfies in Sydney, 300 in Port Kembla and 300 in Brisbane struck against the war, walking off the job on January 15, the day of the US deadline. ABC workers threatened action over censorship of war coverage. Although the government’s sustained propaganda shifted some waverers and Hawke’s poll rating increased, there was never any question of Labor’s deep unpopularity problem being solved by a Western victory.

The first division arises

Precisely because the movement was real, it threw up political controversies. In every city the movement contained a right wing (reflecting the general pressures of bourgeois ideas, the impact of the media, and the dominance of reformism) and in most of the major ones there was a left – although the absence of a revolutionary current made for substantial differences in some places.

The initial question was whether to condemn Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait – indeed, whether such a condemnation was a precondition of building a broad movement. It surfaced in every capital city and led to some splits. The position reflected three weaknesses inside the movement: the idea of pandering to “respectable” public opinion, the idea that international disputes should be settled by peaceful negotiation, and a confusion about the politics of the Vietnam and Gulf wars.

The concept of peaceful negotiation was more than a “common sense” response. It represented part of the Stalinist heritage in the left and the labour movement, reflecting the need of the Soviet ruling class to reach alliances with other imperialist nations. Communist Party activists were schooled in the rhetoric of a moralistic “peace” politics that obscured the class nature of war. Stalinism also took its toll in other ways. In the Vietnam era, anti-imperialism had been associated in the minds of many with an idealised picture of Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Cong as socialist heroes. Stalinists like Bernie Taft and Albert Langer, finding themselves without such romantic associations in the case of Saddam Hussein, collapsed politically and endorsed the imperialist war.

By contrast, the ISO had understood the dictatorial reality of Vietnamese Stalinism and had opposed the US invasion of Vietnam on the basis of self-determination for smaller nations and the need to weaken imperialism. These arguments continued to hold in the new conditions of the Gulf War.

Where the far left was weakest, the emphasis on criticising Iraq was strongest. The WA Alliance for Peace in the Middle East, initiated by broad left ALP members, green activists and church groups, was founded around a statement of principle which began by condemning Iraq. Its rallies heard speakers like state Labor MP Frank Donovan urge a shout demanding Iraq withdraw from Kuwait. In Brisbane, Melbourne, Canberra and Sydney, however, the ISO and some other experienced socialists challenged the right’s position.

In Brisbane, US and allied forces out of the Gulf and the immediate withdrawal of the Australian frigates were uncontroversial demands. But Drew Hutton from Rainbow Alliance, among others, argued that if the peace movement was to have credibility within the wider community, it must demand Iraqi withdrawal. ISO members argued that this would lend credibility to Bush’s war aims. The arguments convinced a majority to accept a compromise formula – “Let the Arab peoples decide”.

In Canberra, the call for an Iraqi withdrawal was raised and lost at least three times. The Peace Network, dominated by right wing peace people, churchniks and “welfare bureaucrats”, organised separately from the coalition but had little impact. In Melbourne also, the “condemnation camp” made little headway thanks to the principled position of key activists and the weakness of the right wing current.

In Sydney, the coalition started on a non-prescriptive basis, but at its second meeting Denis Freney from the New Left Party (NLP – successor to the Communist Party of Australia, CPA) proposed a new set of principles which began by condemning Iraq and did not mention the US until point seven. After a bitter debate, the NLP proposal was narrowly lost. The telling arguments were that the problems of the region had to be solved by the people of the region, that to build an anti-war coalition in Australia we must focus on what our rulers were doing, and that such a coalition had to be open to supporters of Iraq’s annexation of Kuwait which included many Arab-Australians.

A small number of the proposal’s supporters walked out to secretly form an alternative group, the Network for Peace in the Middle East. The coalition survived, did not condemn Iraq, and went on to plan a series of actions. Contrary to the right’s fears, the various coalitions that refused to condemn Iraq succeeded in mobilising some of the largest demonstrations in many years. In Sydney on September 1, a week after the walkout, a Coalition-organised demonstration attracted about 1,500 mainly young people to what was regarded as “the best demo in years”. When the war started, it was the coalition’s march that pulled in more than 30,000 – the network’s on February 10 attracted between 10,000 and 12,000.

In two capital cities where the far left was virtually absent, the “respectability” of the anti-war groups was a barrier to taking the movement forward. In Adelaide, younger activists held a 24-hour vigil on the steps of the State parliament through the first two weeks of February. When the Speaker ordered the police to remove the vigil, the activists were disowned by the Gulf Peace Action Campaign. The emphasis on respectability affected tactical decisions, too. The route of the demonstration on February 16 avoided parliament so as not to embarrass the State Labor government. The march was even routed away from the main shopping areas. When a militant minority of about 120 – including members of the SA Green Party, younger vigil activists and the ISO – sat down in Hindmarsh Square and blocked traffic, Mike Khizam from the campaign asked them to disperse because it might reflect badly on the movement.

In Perth, the conservatism of the movement also affected its activity. Two marches were called, one of 5,000, one of 2,000, but both were funereal. There was no organisation of chants, no co-ordinated publicity for future events. There were arguments against having demonstrations at all because they involved too much hard work, and one demonstration was called off because Ron Kovics, subject of Born on the Fourth of July, could not attend. Meetings were counterposed to demonstrations, non-violent direct action “training” for a few was counterposed to actual mass actions. When young people organised more militant activity, either spontaneously or through Students United Against War, the campaign avoided endorsing it. Respectability meant passivity.

Into the phoney war

After the initial burst of opposition to the US troop deployments in Saudi Arabia the campaign settled everywhere into a steady routine, involving smaller numbers.

In Sydney, the Coalition’s weekly meetings stabilised at about 30 to 40 people representing the more activist, more left wing peace groups and individuals, Arab-Australian groups and left political groups. Despite hostility from the mainstream left, and red-baiting from the rival Network, the Coalition had a degree of success – 45 organisations affiliated including unions like the AMWU, BWIU and WWF. Weekly stalls always received a enthusiastic anti-war response.

In Melbourne the movement divided. The flag-burning incident helped polarise the Gulf Action Committee. Some felt such actions were counter-productive because they attracted racist attention and alienated ordinary people. A number broke away and later organised the Network for Peace in the Middle East. The Gulf Action Committee degenerated into a sectarian rump and serious socialists moved over to the Network.

Despite the lull, political debate continued. Attention now turned to the effectiveness of sanctions and the role of the United Nations. The “let sanctions work” argument surfaced as it became apparent that the US was preparing for war whatever Iraq did.

In Brisbane, while there was always an undercurrent of support for sanctions, it became a more prominent issue as the UN deadline approached. At a rally called by the Arab community on January 15, a number of speakers counterposed sanctions to war, arguing that sanctions were the non-violent way of dealing with Iraqi aggression-they only needed more time to work. A public meeting at Adelaide University before a demonstration on February 16 heard Tom Uren and local campaign leader Mike Khizam argue for sanctions-a full four weeks into the carpet-bombing of Iraq.

Such positions were easy meat for pro-war commentators. Robert Manne put it like this in Murdoch’s Herald-Sun:

After the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait last August the peace movement feebly supported the idea of economic sanctions but fiercely opposed the only means by which they could be made effective-a naval blockade.

… The decision was made at the UN to issue an ultimatum. Iraq would either withdraw or face the might of the UN coalition partners… Although in August it had opposed the UN sanctions policy, (the peace movement) now cried with a single voice: give sanctions a chance.[2]

Regardless of the anti-war movement’s actions, Manne would have found something to criticise. Nonetheless, his attacks had a cutting edge because of the contradictions in the “moderate” position. Not only had its proponents misunderstood the aim of the US and its partners in imposing sanctions in the first place (to legitimise a military build-up in the name of enforcing the blockade). But the sanctions position, like calls for condemning Iraq, also obscured the huge differences between the might of imperialism and a puny regional power. Support for sanctions made the drift to war appear legitimate, because it accepted that Iraq was the main player at fault. And if sanctions were not sufficient…

Support for sanctions turned debate inside the movement into a discussion of what were the best tactics for the US and its allies. It reduced opposition to the war to one based on moral outrage at the suffering (even though sanctions themselves caused enormous suffering). And if the war was wrong only if it caused suffering, then the speed of the US victory could be taken as evidence, with some success, by the pro-war lobby that those who had dragged their heels were trying to prolong the agony. Analogies with sanctions against South Africa missed the point. The struggle for sanctions against apartheid was a just cause, fought for in the teeth of enormous resistance by the major powers. That sanctions exist is to the enormous credit of the black masses and their sympathisers overseas. But who were the main forces pushing for sanctions against Iraq in a cause that was anything but just? The same states that had attempted to squirm out of restrictions of any sort on trade and contact with South Africa.

The debate about the United Nations was more long-lived, reflecting the depth of illusions. In Brisbane, a majority in the committee believed the crisis should be solved through negotiations under UN auspices. Rainbow Alliance and some members of the Democratic Socialist Party (DSP) argued that with the end of the Cold War, the UN could fulfil its true role as arbiter of international disputes. No longer would it be held to ransom by one or other superpower. In Sydney, many in the Coalition supported UN intervention and some sanctions. When the UN gave the US permission to use force in mid-December it was important for many of the activists that there had been an analysis which predicted this.

In Melbourne, at a spring teach-in against the war drive, a debate between an ISO member and a member of the Australian Democrats showed how unclear even many of the better activists were on the question. There was widespread ignorance of the founding of the UN by the pro-war Allies in 1945, its role in prosecuting war and conflict in such places as Korea, the Congo and Lebanon, and the huge sway exerted through Security Council veto (and control of funds) by the five major nuclear powers.

Most importantly, many were prepared to suspend critical judgement of the UN because of a sense of weakness inherited from 10 to 15 years of decline in struggle. In a world where it seemed impossible to challenge the powers-that-be, many were prepared to hope, without any real evidence, that the UN was the final guarantor of justice.

There were those on the left, like the DSP, prepared to feed this illusion, arguing that the UN could be democratised, with power moving into the broader-based General Assembly. This ignored how scores of worthy General Assembly resolutions in support of the Palestinians or Namibians or Kanaks had been gathering dust for years. It also obscured the fact that every delegation at the UN meetings represented a ruling class, none of whom could be relied upon to act against the problems their system brought about The role of the UN had already become quite clear – it had sanctioned the build-up of US troops in Saudi Arabia and had voted for the economic blockade of Iraq to be enforced militarily. The role of the UN had always been and would continue to be to act in the interests of imperialism or not at all.

Those with illusions in the UN had to perform all sorts of political acrobatics. Brisbane PND and others wanted to argue that Hawke’s decision to send frigates to enforce the sanctions was a deliberate misinterpretation of the UN resolution. When the UN voted for the January 15 deadline, it was argued that the resolution was illegal because China, a permanent member of the Security Council, had abstained. These arguments were not only unconvincing – they made it more difficult to mobilise people. Legalistic contortions were no substitute for direct anti-war appeals.

Nonetheless, ISO members were in favour of working with more right wing, pro-UN activists, arguing for instance for the two groups in Sydney to co-operate. This approach did not imply acceptance that the “moderate” position would be more successful in pulling people into activity, but was based on the view that there had to be no barrier to people joining the struggle. It was sectarian daydreaming to imagine that a real movement could be built that did not contain pro-UN or pro-sanctions strands of argument. For the movement to grow, and for revolutionaries to be able to reach a wider audience, it was important that the campaign was based on minimal demands and maximum openness of debate.

By the end of the campaign some reservations had developed about the UN. Now, instead of calling on the UN to resolve the conflict, the argument became that the UN was being manipulated by the US. People drew on remarks by UN Secretary-General Perez de Cuellar that the war was not a UN war. The twisting and turning could not evade the central point – that if the imperialist powers were compliant, the US could fight with their blessing under the UN banner; and that if there had not been a big power consensus, the US would have fought nonetheless, and the UN would have been impotent. This issue will not go away. It represents on a global scale the ever present competition between the ideas of reform and revolution, of top-down change carried through by a well-meaning elite versus the Marxist idea of mass revolt from below. There will be illusions in the UN so long as ruling classes can maintain the image of invulnerability.

Movement responds to the bombing

The first allied bombing sorties transformed the anti-war movement, mobilising protests far greater than those in the early years of the Vietnam War. The long lull had already broken. A non-stop vigil outside the US consulate in Melbourne attracted hundreds on the weekend before the UN deadline expired. In Brisbane, a lunchtime rally on January 15 drew nearly 2,000, and the Coalition grew, with organisers of the annual Palm Sunday peace march starting to attend and the Socialist Left offering resources. In Sydney, a continuous vigil outside the US consulate was the focus for many spontaneous marches around the city, including a 500-strong one down George Street at 10 at night There was a carnival-like atmosphere as people danced and chanted in torrential rain, pulling people out of pubs on to the march and staying to argue politics into the early hours.

Seeing the bombs hitting Baghdad, however, stirred thousands more into action. In Brisbane, 800 people gathered in King George Square on the afternoon the bombing began and voted to march to the US consulate where activists burned the US flag. That Saturday, January 19, between 3,000 and 4,000 took part in one of the biggest and liveliest marches seen in Brisbane for years. On the steps of the US consulate speeches condemning US imperialism were greeted with cheers. In Sydney, hundreds sat down in peak-hour traffic on the day the bombing started. People left bus queues to join in. A spontaneous demonstration broke out in Melbourne, originating in the activity around the vigil and swelling to hundreds as it marched through the mall. The next day, January 18, up to 70,000 marched in what was proportionately one of the largest demonstrations in a Western combatant nation. The momentum transferred to Sydney, where the next day 30,000 marched from the US consulate, stopping for speakers outside the Israeli consulate.

The groups that called these demonstrations were weak and lacked the social roots to mobilise broad layers of people-the initial big turnouts were largely spontaneous. But they also lacked the bureaucratic apparatus to immediately stifle initiatives from below, such as the vigils established outside US consulates. In Melbourne the vigil became a key organising centre, involving hundreds of new people, especially young women, who provided the energy for a series of demonstrations on a daily basis. It was a forum where left wing activists could argue for more radical actions like sit-ins, occupations of the Defence Forces Recruiting Centre, and an invasion of the US consulate, and hold discussions and debates on the key political issues confronting the movement. Above all it was an organising centre for the major rally on January 18. People took leaflets from the vigil to photocopy at work or university. There was a constant presence of young people leafleting the centre of the city. This helps explain why the Melbourne demonstration was much larger than elsewhere.

In Sydney the vigil played a similar role in galvanising activity, but it did not reach the same fever pitch and was not as militant. In part this was due to the depoliticising influence of some small Stalinist and pacifist peace networks.

So the broad mood was for action. But within the organising committees, everywhere older and more cautious than the movement itself, the way forward was far from clear. There were three major areas of disagreement: the role of activity and militancy on the streets; the usefulness of building on campuses and especially in the workplace; and the relationship to anti-war elements in the Labor Party.

Militancy and public opinion: The vigils, demonstrations, sit-downs and occupations were the lifeblood of the movement, giving people the enthusiasm to fight on despite the media lies and the opinion polls. Consequently, ISO members argued for weekly rallies and marches. In Brisbane, Rainbow Alliance, PND and others expressed a viewpoint in reply that was echoed in Perth and Melbourne: that people would get bored with rallies. The groups should have smaller actions that were interesting and would attract media attention. Rallies should be spaced well apart.

The damage that kind of position could cause was illustrated in Melbourne. There had been opposition to calling a second demonstration the week after the war started, but in the end it went ahead and 30,000 marched. (One reason it was smaller was that the Network had closed down the vigil.) The Network steering committee then voted, against ISO opposition, for a three-week gap before the next major mobilisation. Rather than push for more activity that could involve more people, arguments were counterposed about building locality groups, as if large central demonstrations played no role in this.

Too many of the key activists had become used in recent years to holding together shells of campaigns in a hostile environment – building the movement each year from scratch, as one activist bitterly put it in Perth. Yet in a rising movement, the key to taking things forward is involvement – a three-week gap could (and did) feel like an eternity to angry young people who knew nothing of steering committees but wanted to get out and shout their anger and fear in the face of the warmongers. The result of the gap was therefore demoralisation and demobilisation.

The conservatism was also reflected in the universal failure of the anti-war groups to attract, or at least hold, newer independent young activists (with the exception of those groups organised by students themselves). The committees had an “old” (i.e. 30-plus) feel about them, and the atmosphere, whether cosy or hostile, still assumed familiarity with established politics. It was not that locality groups and the smaller activities – vigils, stunts, educationals, banner painting and so on – had no role. On the contrary, they could help feed into the bigger events, building publicity and momentum. But people also needed to feel the strength and confidence that a large demonstration brings – the sense of power that comes from marching down the middle of the road with thousands who agree with you.

There were two ideas of “broadness”. One, from the right, meant gaining the nominal backing of a series of respectable figures and institutions in order to show people the cause was not only correct but mainstream. The other, from the left, meant drawing in broad masses of workers, students and youth into activity against the war without demanding that every aspect of analysis be worked out in advance.[3] If public opinion was to be swung against the war, the militancy of a minority, far from being a barrier, was a prerequisite. Not only did militancy cohere confidence and organisation among the anti-war minority but the willingness to “have a go” was crucial in showing the passive majority that there were people who were angry, and in breaking through the media’s barrier of silence or distortion.

The question of militancy versus respectability was posed most sharply in Brisbane, where organising against the war was hampered by the general lack of democratic rights. On the day war broke out, anti-war demonstrators marched illegally through the centre of the city, had a sit-down outside the Australian Defence Recruiting Office, occupied the road outside the US consulate and burned the US flag without any harassment from the police. But within a week or two the Coalition started having problems getting permits to march.

The search for respectability now led to a retreat. When refused permission to use King George Square for a rally, the Coalition, instead of arguing that this was a politically motivated decision to push the anti-war campaign out of the centre of the city, accepted a more obscure venue.

Building in the workplaces and on campus: Opposition to the Vietnam War had been most effective when translated into industrial action. This time, although some old “strike to stop the war” badges were dusted off, and despite the walk-off by the east coast wharfies in mid-January, the ISO remained largely isolated in arguing that anti-war groups in the workplace were an essential step. (In Melbourne, Workers Against the War, a combination of lower level union officials and rank and file activists, unfortunately played little role.) While official union opposition to the war was welcome, it was far more useful and important to focus on winning people at the workplace level than to orient on a union machine that could take months to react or whose response was usually tokenistic.

There was no hostility to establishing groups in workplaces, rather the idea that organised workers had anything to do with changing the world had become so quaint among Coalition activists that they considered it irrelevant. Yet where workers, often ISO members, took the initiative, there was an encouraging response.

In Canberra, a contact list of more than 300 built up at demonstrations proved vital in building workplace (and campus) groups. The ISO branch took the lead in setting up three regional Public Servants Against the War groups and the ANU Community Against the War (mainly academic and general staff). In Melbourne, groups were set up, among other places, at the State Library, Veterans’ Affairs, the Herald and Weekly Times, DEET state office, the Correspondence School, the Brunswick tram depot and Flemington Secondary College.

Sometimes a leaflet on a noticeboard was enough to attract a handful of people – including some that activists had “written off’ in terms of conventional union work. Even when tiny, the groups raised the confidence of the minority in the workplace and the profile of the anti-war movement. The better established groups brought in speakers and organised contingents to the demonstrations. They also provided an opening for political debate and opened a space for socialists to broaden their influence. Workplace groups were also set up in Brisbane and Sydney, most successfully among university staffs. In the latter city, the Coalition organised some on the job meetings for wharfies. Unfortunately, the US victory came too quickly for the impact or potential of any of the groups to be properly tested.

Organising among students was more popular, if only because substantial numbers were involved (despite it being holiday time) and campus organising had a “common sense” air about it. At Melbourne University, where the soft Left Network is several hundred strong, solid early work meant that by January up to 50 students were coming to weekly planning meetings. The hostility of the National Union of Students, which dodged the issue to avoid embarrassing the Labor government, made little difference because of its weak roots. The campus-level bureaucrats were much more open to the anti-war movement: in Victoria, every union president bar one supported an anti-war circular. Students United Against War quickly established a national presence.

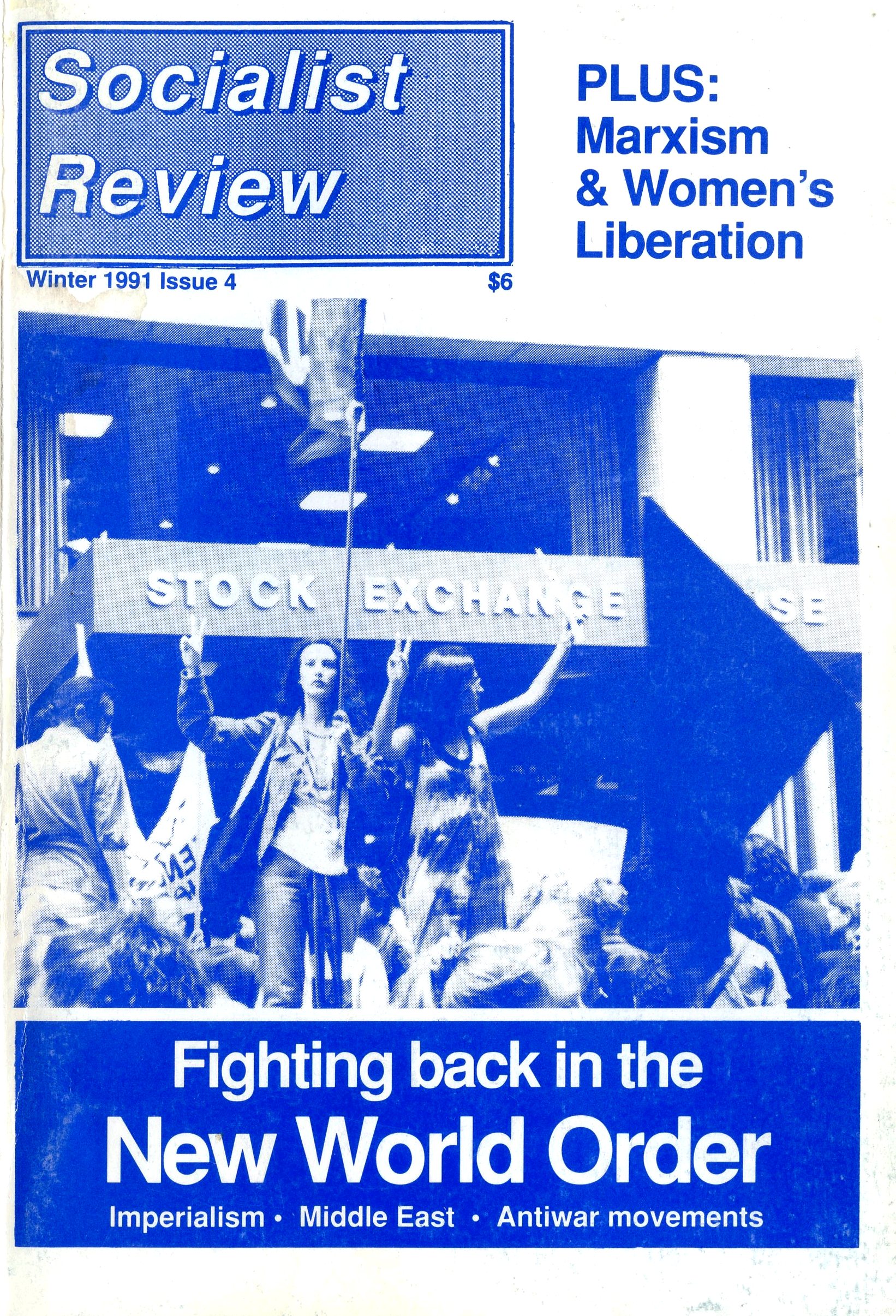

Students flour-bombing the Army Reserve off the campus at Queensland and blockading the Stock Exchange in Melbourne provided some of the most militant moments of the campaign, capturing far more media coverage than many larger but more passive events. In Perth and Adelaide, it was students who attempted to break through the stifling conformity and respectability of the campaign with vigils and sit-ins. Unfortunately, the war finished just as orientation weeks were starting on most campuses and the potential of student organising could not be fully realised.

Labor, the party of war: When not one federal Labor MP voted against the war it merely confirmed what was obvious for the overwhelming majority in the movement – that the ALP was the party of war. The tears of Gerry Hand as he backed the slaughter merely underlined the hypocrisy and impotence of the official left. The logic of Laborism, of attempting to win gains for workers within capitalism, had worked its way through yet again into support for imperialist war. A politics based on using the nation state leads to supporting the “national interest”. Yet the “national interest” can only be that of the ruling class, as workers have no interest in fighting each other for employers’ profits.

The Labor Party is not, however, a monolith. While its generally conservative leadership and politics derive from the trade union bureaucracy that founded it, ordinary members or local office-bearers can genuinely thirst for social change. That gap gives the ALP an ambiguous nature, making it, as Lenin put it, a capitalist workers’ party.

As the Hawke government has ably demonstrated since 1983, the Labor Party defends the bosses’ system – to the point of busting unions, giving helicopters to help suppress the Bougainville Revolutionary Army, and supporting imperialist wars. But because it is based on the union movement it is seen by many workers as their party. It’s a cruel illusion, but because it is – even now – still widely held, it was of major importance to the anti-war movement.[4]

Some people – especially students still bitter over the graduate tax – believed the movement should have no dealings with the ALP in any shape or form. In Melbourne there was some opposition to allowing left wing state MP Joan Coxsedge to address an early rally. At Monash University, activists were said to be reluctant to set up an anti-war group because the Labor Club would want to join.

At some early meetings in Brisbane there were debates over speakers. ISO members argued against inviting Peter White (an ex-Defence spokesperson for the Liberal Party, who was supposedly against the war) because of what the party represented and its support for the war, and proposed a speaker from the Labor Party instead. Most people were opposed because it was a pro-war ALP government which had ordered the frigates to the Gulf. Labor was as bad as the Liberals they argued, so if the Coalition could not have a Liberal Party speaker it should not have a Labor Party one either.

The anti-Labor attitude was also reflected in the way that Democrat speakers became acceptable despite their party’s track record of hostility to the trade union movement, which in other circumstances might have caused embarrassment even to their soft left allies in the movement. In Brisbane, there was a Democrat speaker at every rally.

Hostility to the Labor government and its pro-war supporters was entirely justified, but where that hostility turned into sectarianism it made it more difficult to build the movement. For a start, it created a barrier to the involvement of those ALP activists who wanted to oppose the parliamentary party and the war. In Melbourne, individual Socialist Left members were prominent from early on in the movement. The Socialist Left-dominated Brunswick Council came out against the war. Local ALP members helped launch an anti-war group that attracted 400 to a public meeting in mid-February. The North Carlton branch called for an immediate ceasefire and withdrawal of the Australian warships. A citywide Labor Against the Gulf War organising meeting attracted more than 90 in February. Although support tended to be passive, the Labor left in Sydney and Brisbane did back the anti-war movement.

More importantly, if the movement was serious about gaining mass support among unionists as a prelude to industrial action against the war, the public backing of left wing state Labor MPs like Joan Coxsedge (and 13 others who signed a letter calling for the withdrawal of the warships) and union leaders like John Halfpenny would have been a vital factor.

People like Halfpenny carry vastly more weight in the workers’ movement than the Democrats, to whom many on the left were looking. Who could imagine Democrat leader Janet Powell calling for strikes against the war? More importantly, who could imagine workers taking such a call seriously? By comparison, a Trades Hall-sponsored call in Victoria for action against the war would have had a chance of success, especially if there were workplace anti-war groups active.[5]

Not that everything could have been left to the union bureaucracy. Because of their intermediate position between the employers and the rank and file, their interests are not the same as those of their members. After the war they would have to continue to do business with employers and the State government. To get them to use their influence required mobilising pressure from below. This happened to a degree. The first big demonstration in Melbourne led to Halfpenny addressing the second. Trades Hall took an anti-war position. Similarly, in Sydney, unions sponsored a Coalition benefit and started backing both anti-war groups as the demonstrations grew.

The enemy within: fighting racism and sexism

Arabs and Muslims in Australia had to face some vile racist behaviour as the Gulf crisis escalated. (It was symptomatic of the racist nature of mainstream media coverage that most people had no idea that in this country many Arabs are not Muslim, and most Muslims are not Arab.) The “respectable” pro-war rhetoric of politicians and media commentators was translated by a hard racist minority into fire-bombings, beatings, spitting and harassment. On the streets, women in particular suffered.

Most of the anti-war movement took the need to combat racism seriously. In Melbourne, one of the earlier demonstrations took racism as its focus and marched through Brunswick and Coburg in solidarity with the large migrant population there. Muslim and Arab speakers addressed many meetings and demonstrations. Some leaflets were produced in Arabic.

It was the more “respectable” sections of the movement that had the worst record. In Perth, there was heated debate over the right of a Palestinian to speak at one rally. In Sydney, the right wing Network refused to take an anti-racist position into its platform. Indeed, Network spokesperson Eva Cox promoted racist stereotypes when she said of Hussein on ABC’s Lateline:

When you negotiate, you shouldn’t back someone into a corner, especially if you’re dealing with a male and a Mediterranean one at that.[6]

The fear of being tainted as “pro-Hussein” and the consequent desire to condemn Iraq created an atmosphere that helped exclude many activists from the Australian-Arab community from the movement.

The attitudes taken in the movement towards sexism were more complex. A poll taken during the war by The Australian showed that twice as many women as men opposed the conflict. Democrat leader Janet Powell’s line about war being “testosterone-driven” received a good response at demonstrations, and the slogan ‘‘Take the toys from the boys” was popular. Many women, especially young women, were active. In Sydney, most Coalition spokespeople were female. In Melbourne it was a women’s demonstration that was the first to spill over on to the streets. But there were not many women in leading organising roles or on platforms. Campus groups discussed the barriers to women’s participation in meetings and actions. Lesbians were attacked at one demonstration.

Debate on the war centred around two key points – was it a product of male aggression and violence, and how could sexism in the movement be countered? It was enormously positive that these questions came up at all. Such points were not a big issue during the early years of the anti-Vietnam War movement. The fact that they were raised this time round reflected a much higher degree of consciousness about women’s oppression, even if women’s organisations played virtually no role in the movement.

On the surface, the notion of a “male war” seemed persuasive. The overwhelming majority of the political leaders, the generals and the media commentators were male – a reflection of women’s oppression. As well, many of the victims of war were female. But in this war, as in any other, there were women and men who supported it and women and men who opposed it. Seeing war as a male phenomenon could not explain this. It was not uncommon to hear people argue one minute that men caused war, and to complain the next that men were too dominant in the anti-war campaign.

And while many women bore extra burdens because of the war, some did not. Some indeed benefited – for example those in the higher echelons of the arms industry or female members of the Kuwaiti ruling class. Nor could gender explain who were the victims of war. It is always the women and men of the working class who suffer the most. It is working class people who make up the bulk of military personnel (and of war casualties), whose homes get the worst of the bombing raids (because they tend to live close to the factories which are military targets) and who suffer speed-ups and longer working hours to increase production.

Attitudes to the war were not simply a question of gender. The majority of the population supported it, and that included most women. While it was true that half of the Australian politicians who abstained or voted against the war in parliament were female, the division was not simply along gender lines. Democrats of both sexes and Jo Vallentine opposed the government motion, a minority of the Labor women, mainly from the Left, abstained (not including the minister assisting the prime minister on the status of women), and all the female Liberals supported it. In the House of Representatives, the only person to oppose the government was Ted Mack. Politics, not gender, was the determining factor.

Would it have been different if we had more women leaders? The experience so far is not encouraging. Margaret Thatcher offered the most strident support for military action of anyone in the alliance. Corazon Aquino is presiding over a campaign against left wing guerrillas in the Philippines that is bloodier than the one directed by her predecessor, Ferdinand Marcos. Her policy of Total War involves driving peasants from their villages, gang rape by soldiers and turning a blind eye to murders by the military.[7]

It is argued that these are exceptions, or that women who make it to the top in a man’s world necessarily adopt “male values”. Logically, one would then have to argue that the majority of women who supported the war (or those American women who fought in the Gulf) had also adopted male values (and presumably that all the men who opposed the war had rejected them).

Of course, the argument was not put so crudely. It was usually argued in terms of a “dominant male culture” which is inherently militaristic. Marxists have no quarrel with the notion of a “dominant culture”. But as Marx and Engels put it: ‘‘The ruling ideas of each age have ever been the ideas of its ruling class”.[8] The feminist analysis lets the ruling class off the hook. It is also deeply pessimistic.

If war is inherent in the male psyche or physiology, if it is an irrational, primitive drive for territory or power, if it is caused by arrested development or male hormones, there is really not much hope. According to that logic, men will always be violent and we will always have wars, presumably until we destroy ourselves or the planet.

For Marxists, war is not the product of human nature, which is what the feminist argument boils down to. And from the point of view of those who wage it, war is not at all irrational. Wars arise out of the division of society into classes. Ruling classes, made up of men and women, have always had to defend their wealth against the producing classes they extract it from, which are also made up of women and men, and from rival ruling classes. For the ruling classes this is not a matter of choice or instinct, it is an iron necessity. You fight to protect and extend what you have, or you go under.

That is why the movement against the war was so important. The slaughter could be stopped only if our rulers were forced to go against their class interests. And women had an extremely important role to play in that process. Working class action to stop the war meant involving the 40 percent of the workforce who are female. If students were to give a radical edge to the movement, women would be central – they make up more than half the tertiary population. But because of sexism, their opposition and involvement often took a more passive form.

And here again, feminist ideas about male aggression actually got in the way. Women in the movement who accepted that they should not be political, or that they should not raise their voices or be aggressive because that kind of behaviour was “male” were condemned to the sidelines. As Marxists, we wanted women to develop the confidence to lead, partly because that was important in building the movement, but also, and even more importantly in the long run, because we are for women’s liberation.

To negotiate or not to negotiate

Once the enormity of the damage being inflicted on Iraq and Kuwait became apparent, calls grew for a ceasefire. Terry Flew, writing in Green Left Weekly, put a common position:

As for the anti-Gulf War movement, I hope that it is limited. In other words, [that] our activities domestically and worldwide contribute to securing a ceasefire and a negotiated settlement to the issues of the Middle East which is fair and just.[9]

The DSP also argued for an Arab League or UN “peace-keeping” force in the region to replace the allies. They maintained you had to put up “realistic” slogans and that someone had to keep peace in the region – even if that included nations like Egypt and Syria that were part of the US war effort.

The call for a ceasefire was an understandable response to allied barbarity. A ceasefire imposed on the US by the weight of the mass movement would have been an achievement. The problem was that the right wing of the movement was raising the demand as a general alternative to calling for the US and its allies to get out of the Gulf, once again equating the two sides of the conflict. Ceasefire in the circumstances of early February could only mean US troops remaining, with any negotiations on America’s terms.

When such an argument was raised in Brisbane by ISO members, the reply was that it was a peace movement, not an anti-imperialist movement, and all that people wanted to see was an end to the slaughter. The “ceasefire” that the US has since imposed shows how mistaken this position was. Such an “end to the slaughter” has brought no respite for the Filipinas being raped in Kuwait, Palestinians being terrorised or for the Kurds.

The call for negotiations was even less sensible. Talks could only have taken place on the basis of the real balance of forces. The US was well aware of that – hence the destruction of retreating Iraqi forces and civilians in the final hours of the war – and even after the ceasefire! – and hence the desire on the part of some sections of the US ruling class to take Baghdad. The war was therefore not going to be stopped by appeals to reason and negotiation, but only by the Western aggressors being forced to pull back under pressure of the anti-war movement at home. The demand for negotiations could only demobilise the movement, as it reinforced the idea that history is shaped by the private dealings of “statesmen”. There was a further problem. If stopping the slaughter was the sole concern, then the way was opened for the allies to win grudging popular support on the basis that the heavier the attack, the quicker it would all be over.

Calls for an Arab League or UN “peace-keeping” force were equally naive. The UN could intervene only on the basis of the unanimity of the major imperialist powers – any peace-keeping force would be on the US’s terms. But the same arguments applied to an Arab League force. Client regimes of the West would put troops into the area only with American approval. And would the pogroms against the Palestinians in Kuwait have been any milder with Syrian or Egyptian troops on the streets, given the anti-Palestinian record of those regimes?

Yet such ideas were strong because a liberal pacifism epitomised by the slogan “Give Peace a Chance” was initially dominant. There was little understanding of the imperialist and class nature of the war. The cult of non-violence meant that initially even sitting down on the road was condemned by some as violent. (Although the argument was quickly won in practice in the first heady days on the streets after the bombing started.) The political atmosphere improved as the movement developed and new people learned in struggle. Slogans like “Give Peace a Chance” could be challenged, especially at the smaller demonstrations. Many new people responded to an anti-imperialist explanation of the war and took up explicitly anti-US and pro-Palestinian slogans.

However the initial low level of political understanding and the absence of a sizeable anti-imperialist current severely limited the radicalism and the staying power of the movement. This is important in explaining why the endorsement of the UN so successfully shifted public opinion to a grudging support for the war, and why, within just two weeks of the start of the bombing, the initial explosion of energy had begun to decline. There was no political underpinning to sustain activity once the immediate outrage waned, or to deal with attacks from the right – why weren’t we demonstrating at the Iraqi consulate? – what about Israel? That sections of the left which had once talked of revolution now advocated ideas that fed into the drift to the right indicates how far advanced is the crisis of the left today.

Left in a mess

The crisis of Stalinism in Eastern Europe and the USSR, along with recession at home, was destabilising the left well before the war. As the ISO noted in its perspectives document late in 1990:

The past year has seen the world capitalist system plunge into greater instability than at any time since World War II. The whole post-war imperialist settlement has been overturned… The West has been less affected so far, but US intervention in the Gulf brings with it the spectre of devastation and instability that accompanies any major war.

… the upheavals overseas are being transmitted into our society at the level of ideas. There is a much greater mood of uncertainty about the future, and an ideological crisis on the left… The death of Stalinism, whose ideas were once critical to sustaining a section of militants is the most important element of this instability… Anyone who is or wants to be a socialist has to confront [this] crisis.

Most on the left failed the test. The DSP tailed Gorbymania for a while and then went rather quiet. The self-styled Marxist journal Arena ducked the question, allowing itself a few comments on related cultural matters and then simply taking the “death of socialism” as given. The remnants of the Communist Party, which finally dissolved itself in February, accepted the right’s argument that Stalinism equalled socialism equalled state ownership and moved off in search of the “social market” and a niche in the dinner party milieu. Thus the reformist left, which had provided much of the cadre and organisational cohesion for previous anti-war movements, was at its weakest point for decades as the Gulf crisis unfolded.

More problems were created by the experience of the Hawke government. While a tiny minority were moving to the left, the bulk of society was moving rightwards or becoming less interested in politics. ALP membership was shrinking and increasingly inactive. The Labor left’s credibility and morale had been undermined by its leaders’ role in the government’s austerity drive. It was not unusual for revolutionaries even in big workplaces to find themselves the only political activist in the workforce. On the campuses, only the far left and the much hated Labor clubs had a link to the off-campus world.

Yet the need for clear ideas was urgent. Take the question of Stalinism. For those who had accepted the regimes of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union as socialist, the upheavals of the past two years were not only demoralising but meant they could not explain the role of the Soviet Union in the Gulf War. You needed a state capitalist analysis to make sense both of Gorbachev’s support for Bush (in exchange for a free hand in crushing nationalist dissent in his own empire) and his belated attempts to stop the fighting (positioning the Soviet Union at a slight distance from the US in preparation for the next round of imperialist rivalry).

The ISO’s Marxist politics helped us analyse further aspects of the war that confused others. While many saw Hawke as Bush’s puppet, we argued that the Australian ruling class had always been eager to back imperialist wars to consolidate the support of their major allies, whether Britain or the US. And understanding the ambiguities that flowed from Labor’s base in the organised working class meant we could argue for an orientation to Labor supporters without in any way softening our criticisms of the ALP’s role.

We were able to explain why Israel was no innocent bystander to the conflict, but rather a key ally of imperialism. We could explain the genesis of the “Palestinian problem”, the role of imperialism in partitioning the area and the potential of Arab nationalism. And while many felt there were only two possible positions on Saddam Hussein – outright support or opposition – the ISO drew on Trotsky’s theory of permanent revolution to argue that Iraq had to be supported in the military struggle against the allies, but without the slightest concession to Hussein’s politics. Giving the US a bloody nose was the best way to open the road to revolt from below against dictatorships in the region, whereas if the US won, it would be more difficult to overthrow strong states everywhere. The subsequent uprisings by Shi’ite and Kurdish minorities in Iraq underlined the point in tragic fashion – it was the US that allowed Hussein to crush both revolts.

Our ability to give a lead on the key questions – militancy, the role of the UN, sanctions, negotiations and ceasefire – came from the Marxist tradition. How could you argue against militancy if you understood that the key to change is the self-activity of the working class? How could you argue for faith in the UN if you understood that its component states are weapons of class rule? How could you give any ground to the allies if you knew the bloody history of imperialism? Our politics also helped us address the role of women in the movement – we were unequivocally for challenging the sexism that pushed women to the sidelines, and firmly against glib explanations based on biology that could only confuse and demoralise activists.

On all these points – as well in a series of practical ways – the ISO played a useful role in the movement quite out of proportion to its size. That was possible because we had stood against the left stream on a series of questions over the years.

One of the most popular arguments around the left before the war was that the “new movements” constituted the real strength of radical politics today. Yet ironically those organisations like the CPA, which had done most to hail the movements, played proportionately far less of a role in the anti-war campaign than the ISO, which had emphasised an orientation towards the working class. The reformist left’s partial liquidation into “movementism” undermined its ability to intervene in the biggest movement for years. The maintenance of a separate revolutionary organisation on the other hand made it easier for the ISO to change pace and direction and throw itself into the campaign.

A second, sad irony was that the “new social movements” contributed very little to anti-war organisation. So, for instance, while the overwhelming majority of us who marched against the war were concerned about the destruction of the environment, the Green organisations as such had little to say. Single-issue politics cannot cope with the complexities of a crisis-ridden world.

An understanding of the dynamics of single-issue movements was also essential to withstand the sudden decline of the anti-war campaign. Marxists are not surprised when large numbers of apparently apathetic people are galvanised into activity around an urgent question. But they also understand that without the politics to link that question into the general fight against the system, people can drop out quickly if the issue dies down or if continued activity brings no advance.

While others before the war had tailed Stalinism in various forms, including the trendy ones in Moscow and Havana, ditching much of the genuine Marxist tradition along the way, the ISO doggedly insisted that socialism was about the self-emancipation of workers or it was about nothing at all. At times the argument might have seemed arcane. But without it there would have been enormous pressure to collapse into the trade union bureaucracy, the Labor Party or the movements.

The organisation had to defend Lenin’s idea of democratic centralism, of building a disciplined organisation that combines maximum debate and internal democracy with flexibility and unity in action. The fruits could be seen in the way that every branch threw itself into anti-war work, not on the basis of diktat but because of shared politics and a tradition of collective organisation. The ISO, as a Leninist organisation, had the clearest idea on the left of fostering spontaneity, drawing people into struggle, learning from them, clarifying ideas and raising consciousness. Those groups who had spent most time denouncing the “dictatorial” nature of Leninist organisation were the ones most concerned to keep the movement under the control of bureaucratic committees.

That is why the active participation of revolutionary socialists helped to take the movement forward. In addition to our practical contributions we had an analysis that helped activists stand against the pro-war tide and make sense of a frequently messy and confusing situation. The revolutionary left as it exists today was a product of the Vietnam experience. Although it took years to get the moratoriums, by the time they were organised, there had been countless hours of argument about the war and imperialism to tens of thousands of people, and thousands were involved in anti-war organising. Many joined socialist organisations as a natural consequence.

Because the revolutionary left began effectively from scratch in the sixties, its numerical gains from the anti-war movement were limited, despite years of militant mobilisation. This time round there was a national organisation of 150 members when the war began. We could make gains from even a very short-lived movement because we had clear answers to the complex issues that arose, and a cadre of people to argue for them.

Capitalism will continue to throw up wars and crises. The bigger the socialist influence, the better our chances of beating the warmongers next time.

[1] This article would not have been possible without the help of many comrades, including Alison Stewart, Tony Horne, Rick Kuhn, Chris Hughes, Michael Thomson, Phil Griffiths Tom O’Lincoln, Mick Annstrong, Tess Lee Ack, Sandra Bloodworth, Judy McVey, Tom Orsag, Tom Bramble, Lynne O’Neill and Robert Bollard. I, of course, take responsibility for the final product. This article relies heavily on the experience of ISO members and branches and does not claim to be a comprehensive or nationwide history of the movement.

[2] Herald-Sun, Melbourne, 1 March 1991.

[3] The approaches echoed the competing theories of the popular front and the united front. For a brief introduction to the terms and their significance, see Education for Socialists, 2, Socialist Workers Party, London, 1986.

[4] See Mick Armstrong, Origins of the Australian Labor Party, ISO, Melbourne, 1989, for an examination of the party’s founding philosophy.

[5] Paradoxically, the idea of Trades Hall-led political strikes has held up in Victoria under the Accord, with generalised action over WorkCare and Hoechst, precisely because it has been “safer” for the bureaucracy to lead such action than to fight over wages.

[6] The Socialist, 15 February 1991.

[7] See the interview with representatives of the Philippines women’s group Gabriela in The Socialist, 1 March 1991.

[8] Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, The Communist Manifesto, Pathfinder, New York, 1973, p32.

[9] Green Left Weekly, 25 February 1991.