Editorial (SR Vol 4)

Playback speed:

It is already clear that the 1990s will be very different from the 1980s.

While the previous decade was one of relative stability, and even of sustained economic growth for Western capitalism, we now face the greatest international instability since the second World War. Eastern bloc “socialism” has collapsed in much of Eastern Europe and is in grave crisis in the Soviet Union. Recession has returned to much of the industrialised world. And the beginning of 1991 saw the biggest military mobilisation for many years, as America and its allies set about the destruction of Iraq.

This is the setting for George Bush’s “new world order”, a cynical attempt to re-establish American hegemony. But as Diane Fieldes argues in our lead article, this year’s dazzling display of US military muscle conceals America’s increasingly serious economic decline. And while Bush won a major victory in the Gulf, the underlying instability of world capitalism is likely to unravel his “new world order” faster than he can construct it

Our own rulers inevitably seek to cash in on any new wave of imperialist aggression. Tom O’Lincoln’s article profiles the increasingly aggressive posture of Australia’s military establishment, and discusses how the left should respond.

Because of the importance of oil, and because Western imperialism has entrenched its militaristic client state Israel in the region, understanding the politics of the Middle East is of immense importance for socialists. In her article on Israel and the Palestinians, Janey Stone explains why the Palestinian question emerged as a major issue during the Gulf War. Sandra Bloodworth follows with a study of Arab nationalism, arguing that its revolutionary potential can only be realised if anti-imperialist struggle is combined with Marxist class politics.

Anti-war movements have shaped and re-shaped the Australian left during this century, and the nineties are likely to be no exception. Mick Armstrong’s article on World War I shows how extreme pro-war chauvinism can give way to an anti-war climate, then combine with the industrial struggle to radicalise society. Anne Picot’s account of the anti-Vietnam war movement draws similar conclusions, emphasising that militant action by a determined minority can be decisive at crucial turning point.

David Glanz has written the first major study of the movement against the Gulf War. After the conservative eighties, the anti-war movement of 1990-91 put mass protest action back on the agenda. As thousands of people were politicised by the war, and others began to see old issues in a new light, the movement gave rise to important debates ranging from differences over strategy, to campus and union organising and the role of the Labor Party. David assesses the movement’s successes and failures, and outlines the socialist response to the issues.

The issue of women’s oppression arose in numerous forms during the life of the movement: because women were very active, because of sexism within the movement, and because of the popular view that wars are caused by “male violence”. It is common today for feminists to contend that the Marxist tradition cannot deal with these issues, or with women’s oppression generally. Tess Lee Ack’s feature article argues that Marxism has better answers than any other political current, and just as importantly, can offer the only viable strategy for liberation.

****

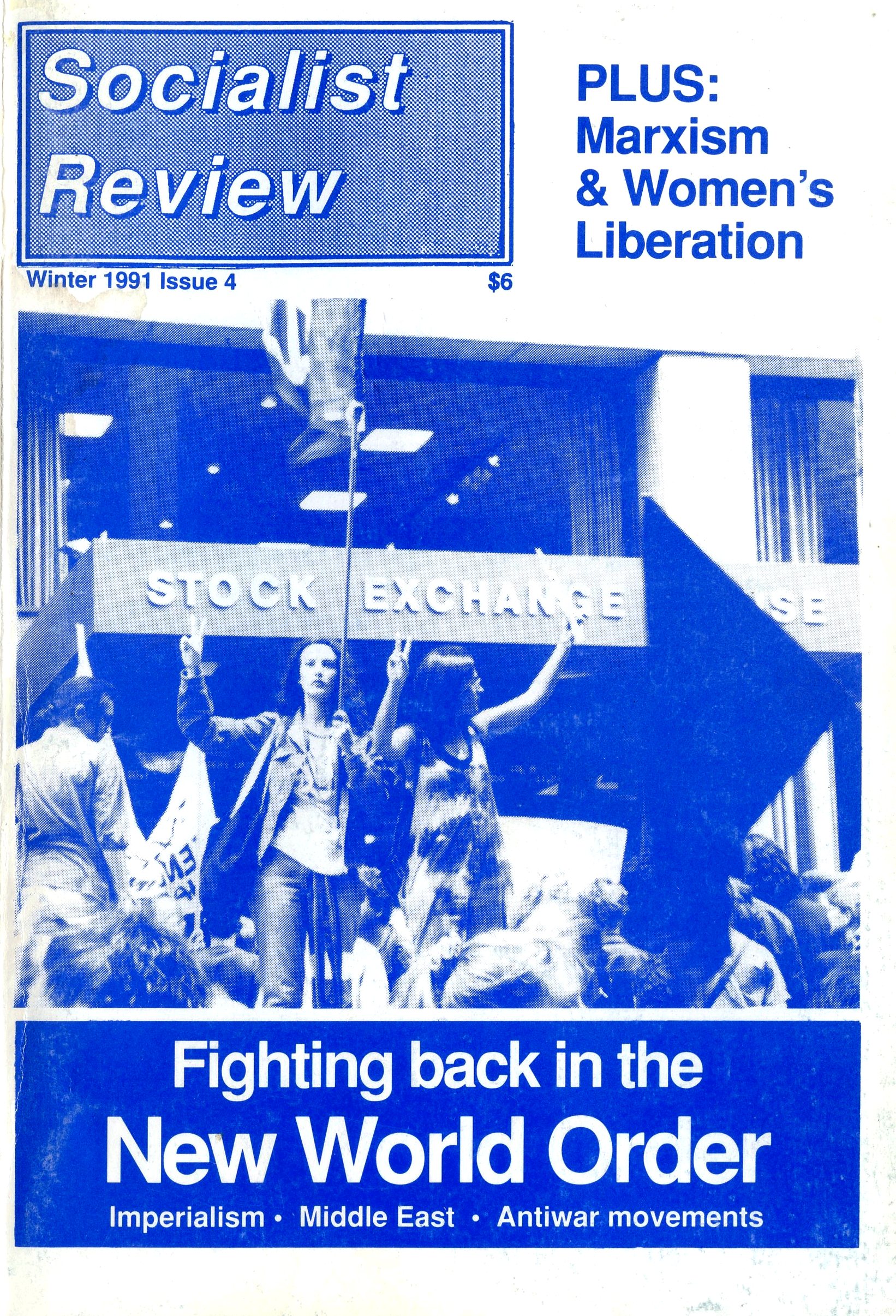

This issue was edited by Tom O’Lincoln and produced by Robert Bollard. Cover photo: Leo Bild. Thanks for assistance to Sandra Bloodworth, Gerard Morel, David Glanz, Mick Armstrong.