Rape, sexual violence and capitalism

Playback speed:

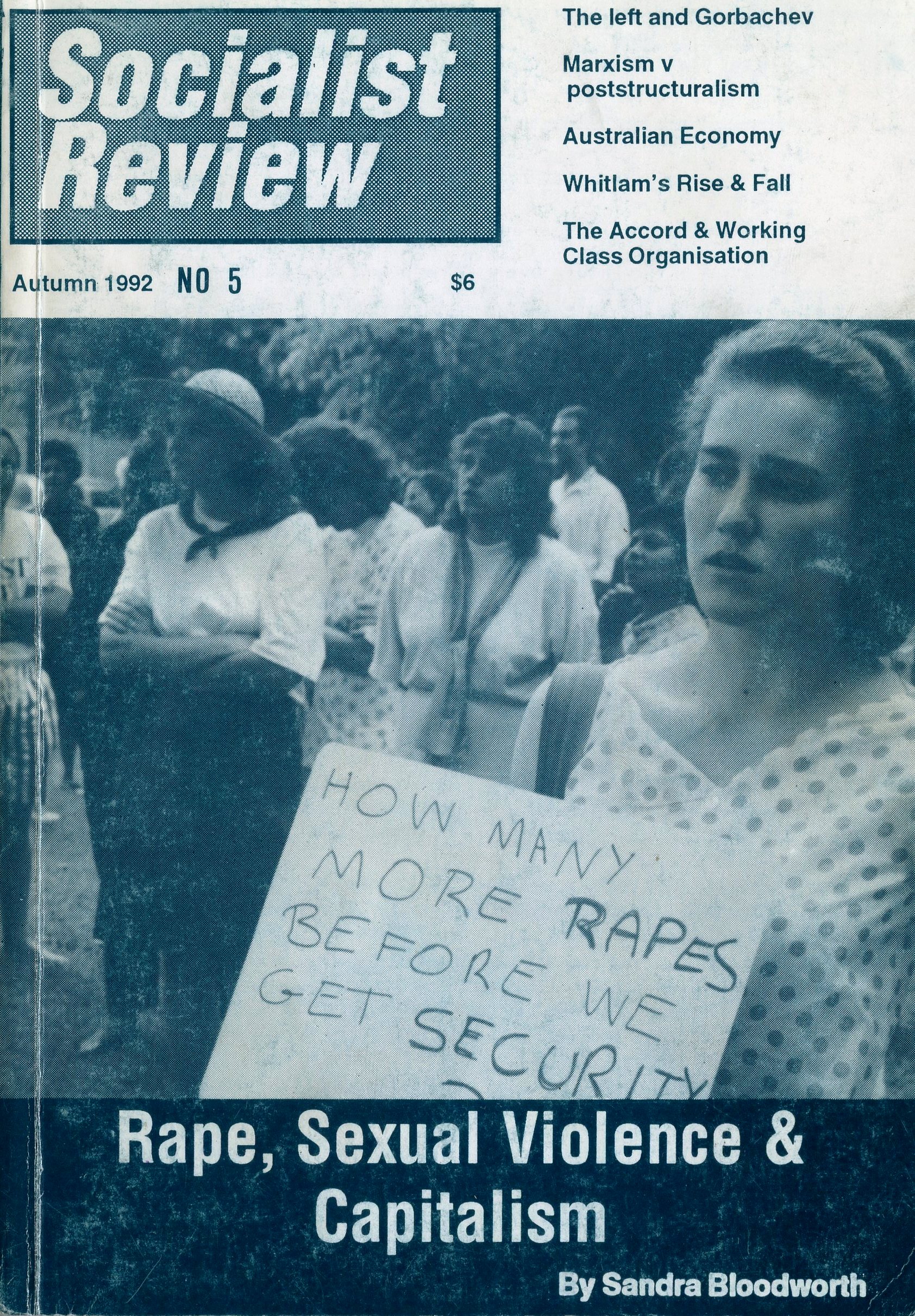

“Break the silence on sexual violence!” was a slogan often heard on Victorian campuses at the end of 1991 as students organised campaigns to force university administrations to provide a safer environment. The annual Reclaim the Night demonstration in Melbourne is one of the largest and liveliest rallies of the year. Whether it be a rape at a club or a sexist judge pronouncing that prostitutes suffer less from rape than “chaste” women, hundreds immediately protest with letters to the papers and street demonstrations. At Queensland University a campaign for improved parking took up the question of safety. Governments have been forced to at least appear to take the issue of violence against women seriously, running TV ads against sexual violence[1] and even providing some funding for refuges. During the 1980s governments, police forces and official bodies held an unprecedented number of enquiries and conferences into violence against women, increasingly concentrating on domestic violence.[2]

This reflects the importance of violence against women as a recurring political issue. There are three main reasons for this. Firstly, the sexism all women endure in their everyday lives, and the violence and rape suffered by a minority. Secondly, the increasing emphasis placed on the issue of violence by feminists. And thirdly, changes in attitudes to sexuality and women’s lives under twentieth century capitalism. As they have been drawn into waged work in increasing numbers this century, women have come to see themselves more as persons in their own right with their own needs and demands.[3] This contradicts the continuing pressure to be the loving wife and mother with few rights in marriage. In Australia the Second World War had an important impact on women’s sexuality and identity which was never completely eliminated. Their entry into previously male jobs in large numbers brought unheard of economic independence. The dislocation caused by war, along with the presence of large numbers of US servicemen alongside Australian soldiers either on leave or waiting to be sent into battle, loosened the traditional ties by which sexuality was controlled.[4] The “sexual revolution” of the sixties brought the contradictions of women’s new position in society into stark relief. On the one hand, the impact of waged work,[5] availability of contraception and limited, but increasing access to abortion meant that women began to be seen as sexual beings with real needs and desires. This was a step forward on the image of them as simply passive housewives.

On the other hand, this emergence of women as sexual beings made it easier for their bodies to be exploited even more blatantly as sex objects. Increasingly society measures good relationships in terms of sex, yet the use of women’s bodies to sell commodities or in pornography reinforces the old idea that women do not have equal rights and needs with men. As Sheila McGregor put it:

Many women’s dissatisfaction with the abuse of their bodies – whether in advertising, pornography, or by sexual harassment and rape – contradicts society’s expectation that they will positively bear the burden of the family as wives, lovers and mothers subordinate to their husbands or lovers.[6]

In this article I examine the themes, analysis and solutions raised by feminists over the last decade or so, with particular reference to recent Australian work, and outline a Marxist analysis of violence against women.

Fundamental changes in women’s lives were made possible by capitalist development. The industrial revolution and the rise of capitalist production disrupted the old feudal family. The new industry drew people from the countryside into new cities where men, women and children were exploited in the factories, mines and mills. This brought about the separation of work and family life. For workers in the industrial slums, the family ceased to exist as an economic unit (though it partially existed as a social unit). But for the ruling class the family remained an important institution for organising their class power and wealth. When they looked for a way to reduce the mortality rates among workers, they naturally turned to the family as a way of having each generation cared for and reared ready for exploitation.[7] Marx and Engels thought the family would die away in the working class, but their prognosis proved to be wrong. Faced with horrendous conditions and little respite from long hours of drudgery, workers turned to the promise of a haven of peace and affection in the family. The new working class family, unlike the old peasant family, was based on mutual attraction and a contract freely entered into – or so it seemed.

The reality is that women’s and men’s lives are structured by the family. And the family structures and maintains the oppression of women. While relations are entered “freely” by both partners, they are not equal. Women do most of the housework and child care, even when they work outside the home. Women are expected to provide nurturing, love and support. Men, who provide the greater part of family income, are seen as the “bread-winners”. This is backed up by unequal wages which make it difficult for any individual family to redress this inequality even if they wanted to. This division of labour in the family is often seen as simply the result of male dominance, and benefiting individual men. Actually, it benefits the ruling class because the present and future generations of workers are cared for out of workers’ wages and by women’s double burden of waged work and home responsibilities. Women experience inequality with their husbands in the family, and at work they suffer both sexual oppression and exploitation as workers. Men suffer exploitation, but not sexual inequality.

The gender roles associated with the capitalist family – strong, aggressive male and nurturing, passive female – pervade all of society through the education system, the mass media, entertainment and so on. No individual can escape them, even if they do not live in the so-called nuclear family, whether they marry and have children or not. It is the inequality between men and women, the contradiction between the ideal life of happiness and bliss the family seems to hold out and the reality of long hours of work, the struggle to make ends meet, the constraints on social life because of the lack of decent child care facilities and so on which make the family a site of frustration and oppression. The use of women’s bodies as sex objects reinforces old ideas of women’s responsibility to satisfy men’s needs. And it is not just men who view women this way. All studies of attitudes show how women internalise this view of their role, causing feelings of guilt and inadequacy if they do not come up to their husbands’ demands.

Throughout the history of class society, women have suffered violence at the hands of men. Capitalism completely reordered women and men’s lives, but it maintained women’s oppression as well as class oppression. While the family is separate from production, it is not unaffected by changes in the workplace. That is why the changes this century have given rise to contradictions which affect women’s lives in the family. The rise of the women’s liberation movement in the sixties was underpinned by the increasing numbers of women in waged work, giving rise to the demand for control over our sexuality, improved contraception and abortion rights. This made it possible for sexual activity to be separated from marriage and procreation. In spite of the ideology of family life, in most industrialised countries today, only about one third of households consist of a man and woman with their children.[8] Attitudes to motherhood have changed dramatically. In the eighties fewer than half the women surveyed in Australia thought motherhood was a career. The number of children born outside marriage was up to 18 percent by 1987. The number of people living alone in 1986-87 was 20 percent of households.[9] It is the continuing contradiction between the promise of these developments and the reality of life under capitalism and women’s continuing oppression which gave rise to concerns first about violence against women generally and then about domestic violence and rape in marriage.

Prevalence of violence against women

Early writings which influenced the modern wave of feminism did not deal with violence against women in any systematic way. But Simone de Beauvoir in The Second Sex argued that virtually all sexual relations between men and women constituted violence. A woman’s first sexual encounter is “an act of violence which changes a girl into a woman”. She uses all the language of unequal relationships: the woman is “taken”, she is “invaded”, she “yields” to men’s sexual advances.[10] Susan Brownmiller was influential in promoting this kind of analysis with her book Against Our Will, published in 1975. For de Beauvoir “this has always been a man’s world”. And “the female…is the prey of the species”.[11] Brownmiller argued that rape “is nothing more or less than a conscious process of intimidation by which all men keep all women in a state of fear”.[12] This theme has become prominent, at times blurring all sexism into the category of violence. It is the case that the everyday sexism of the wolf whistle, anti-women jokes, put-downs, etc. create the environment in which violence from a minor nature to forcible rape and battering can occur. But to blur all these situations into one is to ignore the specificity of each and to lessen our understanding of the social relations between the sexes which lead to violence against women.

Brownmiller’s book, apart from its serious theoretical problems, has a weakness which has become increasingly apparent: its concentration on “stranger danger”, rape as a violent attack by strangers.[13] It is now recognised that most violence against women occurs within the walls of the family home.[14] Today, with so much emphasis on sexual violence, especially in the family, it is hard to imagine that only fifteen to twenty years ago, even feminists were reluctant to discuss the issue and accepted ideas that are now recognised as part of the ideology which minimises women’s access to support and defence against violence. Brownmiller states that until a discussion of rape she attended in 1970 she thought “rape wasn’t a feminist issue”, that “the women’s movement had nothing in common with rape victims”.[15] Beatrice Faust is quoted in 1977:

…in many cases women’s behaviour helps the belief [that they “asked for it”] along since the ladies act as if they want to be raped. They shorten their dresses to fanny pelmets and lead with their nipples through see-thru’s. They drift calmly into situations that are throbbing with sexual possibilities, typically, drinking with a man or getting into a car and driving to a lonely place, even undressing. They refuse to admit the sexual potential in a situation until it is too late to chicken out without getting plucked.

She continues by talking of the pressure for women to “draw the line”, and while these women may actually want sex, they do not always know how or where to draw the line, “by which time the men concerned may feel that they have dues to collect”.[16] Diana Russell writes that even in the eighties, feminists in the US were reluctant to take up the question of rape in marriage.[17] It is worth reminding ourselves of this incredible shift in attitude even by feminists who today would correctly insist however we dress, wherever we go, yes means yes, and no means no. In student newspapers it is asserted over and over again, echoing Brownmiller, that sexual violence, and in particular rape, is a means of social control of women by all men. Unless we want to argue that earlier feminists were complicit in this violence, their ideas require some explanation. We can only do this by developing an analysis of such violence as a consequence of class society, the ideas of which affect us all.

A major reason why violence in the home was covered up was the ideology of the family as a sanctuary of love and private life, not to be invaded by public scrutiny. Of course this sanctuary is “the man’s castle” and women feel pressured to be available for sex at all times. The law did not recognise marital rape in most states until the late seventies or even into the eighties.[18] So it is not surprising that common sense folklore denied it. Russell found, in developing interviewing techniques for her study of just under 1,000 women, that it was extremely difficult to ensure women would report rape by their husbands. The interviewers were eventually told not to use the word rape, but to ask if they had experienced unwanted sexual activity with their husband. Only six of the 87 women raped by their husbands mentioned it when first asked “at any time in your life, have you ever been the victim of rape, or attempted rape?”. Virtually all thought they had been sexually abused, but not raped, although some later described the experience as “like rape”.[19] Rape is a specific question, and marital rape was not recognised in most US states at the time of the survey. Nevertheless, what constitutes “abuse” is also a subjective assessment. Many women who expect to be at their husband’s beck and call may not regard as abuse behaviour which would be so regarded from other men.[20] This hidden violence in the family was masked even more by the lack of welfare or divorce laws which enabled women to leave abusive relationships easily. Part of the explanation has to be that it is a minority of women who suffer abuse. Russell, whose survey is one of the most methodologically rigorous and therefore more reliable as a pointer to the extent of violence, found that 21 percent said they had suffered violence from their husband and 26 percent unwanted sexual experience.[21] Given that violence is most prevalent in less privileged, less well-off families,[22] many middle class women in the women’s movement are not likely to have had personal experience of such abuse.

So the interesting question is not so much why it took so long for feminists to take up the issue of domestic violence, but why it has become the issue. Just to pose the question is to challenge widely held notions about feminism. There is often an assumption that feminists were the champions of women’s rights in opposition to the old, “sexist” left who never had anything of use to say about women’s oppression. Katharine Susannah Prichard’s novel, Intimate Strangers, written in the mid-1930s, indicates that Communists had insightful and subtle ideas about domestic violence decades before it became a feminist issue. Prichard dealt with the social pressures which force young women into unwanted marriages and the family pressures to endure violence which are underpinned by women’s low expectations of marriage and love. Dirk confides in Elodie about the attitude of her husband Ted’s mother to his abuse:

She’s seen me black and blue with Ted’s caresses. She says marriage is a disgusting business, at first; but you get used to it. I should give in to Ted more. He’s crazy about me… Is it devotion to humiliate me so?… I wanted to play fair: to be a good wife to him – but Ted’s made me loathe him…[23]

This quote also takes up a theme which is revealed in studies where women voice their feelings: that you can’t really expect much from marriage – it may even be “disgusting” – but it must be endured. This novel is an answer to the mythology widely accepted among feminists and most of the left today that only feminists have been able to deal with women’s oppression. Clearly, Prichard, a leading Communist Party member from the time of its formation in the early 1920s, was far in advance of the thinking of the new women’s movement of the sixties.

It may be tempting to think the reason domestic violence became more of an issue was because violence was on the increase, as the press often tries to make out. An article in The Bulletin in October 1991 stated:

There is no doubt that violence against women has increased both in ferocity and frequency. In the past decade Queensland…has seen the number of sex offences reported to police rocket from 1500 in 1980 to more than 4000 in 1990… Brisbane’s rape crisis centre now sees 300 cases of sexual assault a month; a few years ago it was about 100 monthly. Similar rises have been reported in other states.[24]

Increases in reported sexual assault do not necessarily reflect a rise in violence. It may, as Grabosky pointed out, reflect changes in police practices, changes in social attitudes which mean more women feel able to report the attack, or even the fact that the legal definition of rape has changed.[25] There are several reasons for the shift in emphasis which intersect and reinforce each other. Firstly, the continuing increase in the number of women working raises expectations of what relationships should offer. Women who feel relatively independent are likely to be more self-confident, more able to get out of a relationship, so they are not prepared to accept the same level of abuse as previously. There is quite a lot of evidence to suggest most women do not passively accept their situation (contrary to the efforts of many academic sociologists to establish otherwise). Eighty percent of women contacted by the Queensland Task Force attempted to leave at some time. American studies back up this figure with one finding that 75 percent of abused women left the violent family situation.[26] Even a study of adolescent women, who could be expected to have the least self-confidence, found that a majority were able to stop the attack and avoid rape. Where the assault was perpetrated by a date or boyfriend, two-thirds of the relationships changed and 87 percent ended.[27] Women’s ability to assert their own interests was improved from the mid-seventies when divorce laws began to be reformed and later, when rape in marriage acknowledged abusive behaviour as criminal. The provision of welfare, insufficient as it is, can make the difference between staying or leaving an intolerable situation.[28] Many studies quote women as giving more ideological reasons, such as commitment to the family, feelings of guilt or even believing they were to blame, for staying in a marriage they hated. This should not blind us to the way economic circumstances constrain the options open to an individual, thereby limiting their view of their position. Economic and ideological factors feed each other. Once the material circumstances change, there is a space for new ideas to take root and influence a person’s actions.

These factors intersected with a shift in the women’s movement, away from class politics which promoted women as fighters, to an emphasis on women as victims. McGregor and Hopkins put it very smugly when they took up Ann Curthoys’ argument that the social base of modern feminism was the growing numbers of women in middle class professions:

For these middle class women, the disadvantages they experience are associated with gender and not class. For this reason the women’s liberation movement rapidly disentangled itself from the class concerns of its founders and began to attract adherents who had no interest in socialist or left-wing politics.[29]

Brownmiller, with her theory of universal male violence, was influential in this shift. However, her study dealt with crime statistics and “stranger danger” which quite clearly show crime, including rape, is more prevalent among the most disadvantaged in society. So she admits, despite her assertion that all men use rape to keep all women in fear, that

there is no getting around the fact that most of those who engage in antisocial, criminal violence (murder, assault, rape and robbery) come from the lower socioeconomic classes… Ninety percent of the Philadelphia rapists “belonged to the lower part of the occupational scale”.[30]

Her conclusion illustrates at best the absurdity, at worst, the elitism and anti-working class attitudes that are the consequence of trying to ignore the real social inequalities which underlie a large percentage of crime and violence:

Rape is a dull, blunt, ugly act committed by punk kids, their cousins and older brothers, not by charming, witty, unscrupulous, heroic, sensual rakes, or by timid souls deprived of a “normal” sexual outlet… And yet, on the shoulders of these unthinking, predictable, insensitive, violence-prone young men there rests an age-old burden that amounts to an historic mission: the perpetuation of male domination over women by force.[31]

If rape is as much a part of human relations as she asserts, she has to come up with a more convincing explanation for class differences in the rates of stranger rape than this! Studies of crime rates show that rape is often but one form of violent, alienated behaviour, especially by youth in poor and socially disadvantaged communities. Brownmiller drew heavily on Amir’s study of Philadelphia police records. She found:

Ninety percent of the Philadelphia rapists “belonged to the lower part of the occupational scale,” in descending order “from skilled workers to the unemployed.” Half of the Philadelphia rapists had a prior arrest record, and most of these had the usual run of offenses such as burglary, robbery, disorderly conduct and assault. Only 9 percent of those prior records had been previously arrested for rape. In other words, rapists were in the mold of the typical youthful offender.[32]

A later FBI report showed that more than 70 percent of all arrested rapists have prior records and over 85 percent are reported to repeat crimes in descending order of frequency: burglary, assault robbery, rape and homicide. If this were the most common form of rape, it would be fairly straightforward: rape is one aspect of the violent existence of disadvantaged youth. The fact that Brownmiller concentrates on this data makes it even more ironic that she was influential in shifting the politics of feminists away from class. It was this emphasis on “stranger” rapes which led to the categorical assumption that rape has nothing to do with sex, but is simply an act of violence. However the question is far more complex than that – in fact many rapes are at least partly to do with sex. Sheila McGregor makes a distinction between three types of rape: date or acquaintance, marital and stranger.[33] Her material on date rape was based on surveys of adolescents in the US over a five year period. In contrast to some studies, the definition of forced sexual behaviour was quite wide: touching sexual parts, and pressure brought to bear from verbal to physical beating. On this definition, over a three-year period between 7 and 9 percent of female adolescents reported some form of sexual assault. Ageton, who compiled the study, summed up the attitudes and motivations involved in these unwanted sexual acts:

A review of the description of these incidents suggest that a number of them reflect the classic dating scenario where the male presses the female for sex. Most of these incidents did not involve more than verbal pressure, and a high proportion were unsuccessful…

A Ms magazine survey of US college students found that just over a quarter of the women considered to have been victims of rape or attempted assault did not consider themselves to be rape victims. Almost half had sex again with the same man. Of the 8 percent of men who had been involved in forcing sex on a woman, 75 percent said they had never forced an unwanted sexual act on a woman. McGregor concludes:

This is a clear indication of the difference between the sexual attitudes of men and women towards sex. It also shows how inequality between men and women affects the most intimate relationships between them.

It also shows how difficult it is for women to accept that a man they care about may rape them, or to even recognise rape for what it is. There is the pressure of not knowing whether the man will want to date again if he does not have sex, the feeling that a woman is expected to be available (an attitude more prevalent for adolescents today, with the liberalisation of ideas concerning sex out of marriage). There is the perception created by TV and films that a young male is less than a man if he does not go all-out for sex. All of these contradictory feelings and ideas, combined with inexperience and lack of knowledge about sex, lead to a breakdown in mutual respect and can end in rape. To say this kind of rape is not about sex is to ignore the dynamic of sexual relationships among youth. They are bombarded with images which imply that women who are not sexy and available are inadequate. Young men watch films and TV, read books and newspapers which promote the idea that men should take sex from women, that emotions and caring are only for wimpy women.[34] Of course, forced sexual acts and rape by dates and acquaintances is not about what we would like sex to be – but it most certainly is about sex the way it is under capitalism.

The other kind of rape which is not always simply an act of violence, although it sometimes is, is marital rape. Prichard dealt with wife rape which, as we have seen, has been a difficult subject even for feminists of the “sexual revolution” to deal with openly:

His head fell against her neck. He was kissing her arms and breast with the loose devouring mouth of rage and hunger.

“Greg!” Elodie besought, moving away from him. He clung heavily, overpowering and crushing her. “Don’t, don’t! For God’s sake,” she pleaded, “I’ll never forgive you.”

He laughed ruthlessly, undeterred, overwhelming and destroying her resistance. When she lay weakened and vanquished, he tried to be tender again, smoothed her hair: whispered, “Elodie…Elodie, darling.”

… Her immobility, air of suffering, troubled him. She looked extraordinarily helpless, violated in some supreme way. He was really sorry for her.

“Elodie? What’s the matter, darling? What is it? You know I love you.”[35]

Prichard dealt with the confusion between love and possession by men of women. They had been great lovers, and had children together with affection. Now their relationship was eating away at their sense of individuality. Elodie, like many women tied by the bonds of those years, felt a sense of responsibility not just for the children but also for Greg. She continued her life with him in spite of that horrible afternoon.

Diana Russell’s excerpts from women’s accounts of sexual relationships with their husbands or lovers once again show the very blurred distinctions at times between sex and violence, consent and refusal. To the question “Any other unwanted sex with him?” one woman replied “It’s hard to say when you’re married…it’s hard to delineate what’s wanted and what’s not. You can’t just call it quits and go home!” Another woman talking of unwanted sex with her husband said:

Once I’d call it that [forced]. Another time it was kind of half and half…it wasn’t like the first time but still, I felt he forced himself on me. I guess the difference is sometimes a man wants to have sex and you don’t, so he just imposes it on you. But there’s no anger or violence or meanness; it’s just having his way.[36]

These statements are typical of the feelings which dominate the surveys. In many cases, because the woman feels she cannot refuse sex because of the expectations of marriage, the husband may not think of himself as ever having raped his wife. Of course their behaviour is uncaring and insensitive, ignoring their wife’s sexual needs, of which at times they appear to be oblivious. But to say this kind of unwanted sexual activity (l call it this because in many cases the women do not feel it was rape, or that it was forced on them, because they accepted it) has nothing to do with sex is to gloss over the incredibly stunted and unfulfilling personal lives women and men have compared with the happy, smiling stereotypes of the TV ads, In some ways, it is surprising that it is only a minority of women who suffer sexual assault and a minority of men who perpetrate it. This fact is an optimistic sign and affirms the refusal of the oppressed, both men and women to surrender their human sympathy completely in the face of the barrage from capitalism which degrades everything including sex to money relations.

Class

The crime statistics Brownmiller relied on showed a clear class bias towards the disadvantaged involved in rape. However the question is far more complex when we look at domestic violence. Obviously men of all classes are influenced by the sexism of society, and are likely to see marriage as a licence to dominate their wives, because unequal relations exist between men and women of all classes. However, there is debate over whether sexual abuse occurs at different rates in different social groups and if so, why this is the case.

Because of the political shift away from class politics, not just by feminists, but in the academic world and even sections of the left, the analyses and surveys are heavily oriented towards trying to prove that class plays no role. One way of doing this is to put up straw positions. Jocelynne Scutt argues that her study “denies the theory that feelings of powerlessness and frustration solely underlie child abuse…” [my emphasis].[37] Of course, these would not be sufficient to explain all abuse in the family; firstly it has to be explained why the overwhelming majority of abuse is by men towards women and adults to children. So the question of gender and attitudes to childhood, the role of the family, etc. have to be part of an explanation. She continues to make a more reasonable claim that her survey does not prove these feelings “are experienced mainly by lower socio-economic strata men. However, her study cannot tell us anything conclusive about the incidence of violence or reactions of individuals to their situation because it is too small a sample (312 participants) and is based on replies to a questionnaire.[38] In another example she knocks down the argument that “unemployment inevitably increases wife-beating” [my emphasis]. Such a statement would be absurd: today there would be a massive outbreak of marital violence, as unemployment skyrockets. But she does admit that unemployment made it more difficult to leave a violent situation, which does mean more violence for that woman than if she were well-off.

There is an interesting contradiction in some of the arguments. Scutt is determined to discount economic pressures, or feelings of powerlessness arising from bad living conditions, an oppressive job and so on. She even suggests that men of higher socio-economic position may be more violent because they internalise the social message of men’s dominance more thoroughly. She speaks for many feminists when she puts the emphasis on the fact that “fathers are rulers in their household; he who rules is powerful”.[39] Yet when it comes to child abuse carried out by women, she accepts that feeling trapped, unable to cope and economic stress are contributing factors.[40]

In spite of all the disclaimers about social class, in Family Violence it is accepted without question that Aboriginal communities suffer a high level of domestic violence. Liz Orr rejects the analysis that class may be significant, but then says “violence is endemic in contemporary Aboriginal society” – why?

The present situation of Aboriginal violence is clearly determined by extreme conditions of impoverishment, cultural subjugation and spiritual denial which are consequent upon a white male history of colonisation.[41]

Diane Kirkby constantly denies the importance of socio-economic or class factors, but states that:

In some Aboriginal communities, levels of family violence are so high that up to 90 per cent of families are affected. The extremity of this situation is an indication of the effects of white colonisation.[42]

There is an assumption that if we can attribute the violence to “colonisation”, “cultural subjugation” or “spiritual denial”, then it is nothing to do with socio-economic factors, that the theories of class have been defeated. “Colonialism” is presumed to be something other than imperialism, or class society, which axiomatically impacts negatively on the lives of the disadvantaged and oppressed. The fact that cultural subjugation and spiritual denial lead to increased levels of violence proves, rather than disproves, that unequal relationships between women and men can only be understood in the framework of a class analysis. This reveals a problem which occurs throughout the writing on the subject: lack of clarity about what a Marxist analysis is. So for example Kirkby states:

Whilst the experience of family violence may differ according to factors such as socio-economic group, class, culture, race and the age and health of the victim, it has not been demonstrated that these factors play any causal role in the origins of family violence.[43]

She maintains that domestic violence can best be understood in the context of unequal power relationships between men and women. There is, for example, a high correlation between traditional views of women’s economic subordination to men and approval of husbands’ violence. She argues that to view family violence as an aspect of normal interpersonal conflict is misleading because all conflicts do not lead to violence and some men attack their wives when there has been no specific conflict. She is concerned that such an approach leads to focusing attention on preserving the family unit rather than “empowering” the abused women. She concludes:

Women’s experience of family violence, which must be the starting point for any analysis of family violence, does not allow the separation of their gender from their victimisation by their partners.[44]

Orr makes a distinction between causes and contributing factors, which seems to be what Kirkby is getting at. Class deprivation may contribute to family violence, but it is not a cause. This differentiation is too rigid and leads to an attempt to isolate one factor which can be said to be the cause. This is very fruitful for “proving” that the unequal relations between men and women are the only cause, because the fact is of course, it is women who are on the receiving end. However this is not a productive approach if we want to understand how the situation can be changed. And it does not explain why a majority of men do not use violence. Unequal relations between men and women alone certainly do not explain the conditions mentioned by these writers among Aborigines. They are forced to acknowledge the effects of factors other than gender. Orr admits:

it is possible that family violence is unevenly distributed across socio-economic levels, and it is certain that women’s experience of such violence is influenced by socio-economic issues…women in occupations of higher status tend to stay in violent relationships for shorter periods of time and experience violent attacks far less frequently than women in occupations of lower status. It follows that women who face unemployment or only have access to low paid jobs have a higher likelihood of staying and being beaten more frequently.[45]

So even if we start with women’s own experience, as Kirkby wants, we cannot escape the effects of economic and other factors on their likely victimisation. She herself admits that “women engaged in full-time home duties have been found in a number of studies to suffer a higher rate of abuse”.[46] What we have to uncover is how the various economic, class and other factors intersect with the general oppression of women. In their concern to constantly put what they call “men’s power” at the centre, these writers cannot theorise the totality of women’s experience. To see the family as a place of conflict and tension does not lead to defence of the family. It can just as easily lead to the conclusion that as the source of women’s oppression, it should be destroyed. The fact is, those who emphasise “male power” do not advocate this at all. They are too concerned to demand that men change their behaviour – and as we shall see below, they’re not too fussy about whom they take on as allies in order to achieve this. Or their analysis remains vague and confused. At the end of her article, Orr can only say lamely that violence against women “cuts across all age, class and race barriers, although the social response and cultural meaning of this violence is likely to vary”.[47]

Jan Horsfall’s book The Presence of the Past attempts a more theoretical analysis within the framework of patriarchy theory. Despite partial insights she cannot offer an analysis which explains why violence occurs. In the introduction she quotes Connell:

What entitles us to talk of a unity, a coherence, and system and hence “patriarchy”, at all?[48]

She blithely ignores this potent question, asserting that male batterers of women gain “significant advantages” by their violence. What they are remains a mystery given that “the non-batterer can wield power in the same arenas without resorting to violence”. All we get is a hotchpotch of theories which see a fundamental division in society between a supposedly public, “male” domain and the private, “female” domain. Trade unions and the workplace are simply another place where working class men experience “male” solidarity and “retain some power in the public domain”.

A consequence…is that women have very little power in the public domain deriving from either the family or wage-labour.

The ignorance of such a statement is breathtaking, given that women make up over 40 percent of the workforce. The workplace is where women can gain potential power, as working class men do. Trade union organisation (and struggle, which she never mentions) is precisely where there is the greatest potential for unity between men and women which can undermine sexism and violence towards women.

The chapters on the structural causes of violence towards women remain purely descriptive. Aspects of Freud’s and others’ theories are thrown together to describe what are supposedly the ways male and female gender attributes are constructed. The serious weakness is that it assumes children universally grow up in a two-parent family. Only a third of families live this way in Australia today, divorce and remarriage are common, and in some countries in the less developed world workers often live in compounds and hardly experience this kind of family at all. Her narrow-minded, psychological approach blinds her to the fundamental problem. Capitalism depends on the ideology of the family as a justification for the lack of socialised facilities and for the burden women workers bear in reproducing the workforce. So the male and female stereotypes are produced socially, via education, the media and so on and backed up by very material discrimination against women.

The book is riddled with logical contradictions and muddle. She says that violence in the family occurs irrespective of class, income or social situation. Two pages later, she lists dissatisfaction at work, combined with other factors such as low self-esteem which “could account for the higher rates of wife battering amongst the working classes”.

The confusions and lack of clarity of these more theoretical works are reflected in more popular articles. For instance, in a pamphlet put out at Monash University, two authors argue that it is in the “male ruling class’s” interests for women to be passive sex objects.[49] This implies it is not in the interest of the females of the ruling class. But for women’s oppression to be seriously challenged, the class society which gives rise to it must be threatened. Whenever this has happened, ruling class women have not sided with the oppressed, but have supported their male counterparts’ attempts to put down such a challenge. Once again there is the attempt to separate women’s oppression from class society. Repeating a common theme, the editorial states that violence against women “cuts across race, class and religion”. This is true up to a point, but as a statement on its own, it tells us very little. As we have seen, it repeatedly has to be modified to account for differing levels of violence in different social layers.

So far I have argued that violence against women is the consequence of the way capitalism structures women and men’s lives into different gender and class roles. But where does pornography fit in – is it a cause of violence? Some feminists such as Brownmiller, Andrea Dworkin and Catherine Mackinnon claim it is. A popular saying is “porn is the theory, rape is the practice”. Scutt was asked by Rebellious, the women’s student paper at La Trobe University, “Does pornography cause more violence?” She replied, “We are never going to get an answer that is conclusive”. Then she went on to equate pornography with violence. This is a popular idea promoted by groups such as the Coalition Against Sexual Violence Propaganda:

C.A.S.V.P. does not seek to establish a causal link between SEXUAL VIOLENCE PROPAGANDA and sexual violence, as it perceives SEXUAL VIOLENCE PROPAGANDA to be a form of sexual violence.[50]

There is an assumption that pornography is distinguished by its depiction of violence. McGregor found this was not so: 90 percent of pornography is routine sex. The levels of violence in Playboy have decreased since 1977 to below that of kids’ comics. Some researchers report that porn is overwhelmingly boring. Experiments found that films about sex had no impact on men. Films about violent rape were found to produce increased levels of aggression in men if the woman being raped was shown to enjoy it or if the male viewer had already been made to feel angry with a woman. These studies were used to argue that pornography causes violence and so should be banned. McGregor comments:

Ironically, these findings seem to point to quite different conclusions from those drawn by the researchers themselves. In real life many women stop sexual assaults from being completed… Nor do women enjoy such assaults. The difference between the imagery and real women is crucial, as is the difference between being a passive viewer and an active rapist. Real women try to control what men do to them and, in the main, real men respond. In other words, the research method is fatally flawed because it is not based on any notion of human interaction, but on a simplistic behaviourist stimulus-response view of human actions.[51]

Pornography is a reflection of the stunted sexual relationships under capitalism, not their cause. The growing market for it is a consequence of the changes already talked about. Young people grow up in a world full of sexual imagery, but actually learn very little about sexuality. Many of them turn to porn out of curiosity or even a substitute for real human relationships. To equate pornography with violence is dangerous. Scutt explained this point to mean that the industry exploits the women it employs, which it surely does. But if a woman’s employment per se is violence, how then do we distinguish it from battering and rape? Were there no distinction made between prostitution and rape, a prostitute would have no rights against a rapist. It is interesting to note that in the most recent books, the question of pornography is not taken up. This is a welcome shift in the arguments, especially if it indicates a recognition that pornography has not been shown to cause more violence.

The Marxist alternative

Marx argued that the way production is organised is fundamental to all aspects of social relations in any society. Under capitalism, the mass of producers is divested of any control over the means of production. Instead, workers’ ability to work is itself turned into a commodity. This very activity, which should be creative and life-affirming, becomes nothing but a chore, producing wealth for those who dominate our lives, and in fact increasing their power over us.

The devaluation of the human world grows in direct proportion to the increase In value of the world of things. Labour not only produces commodities; it also produces itself and the workers as a commodity and it does so in the same proportion in which it produces commodities in general.[52]

This means that the products of workers’ labour stand as alien objects, as a power beyond and opposed to them. This alienation means that for the worker, life appears to be dominated by the products of labour over which she/he has no control. Instead of labour being the source of the needs of life, it becomes drudgery and the means by which capital dominates society. Labour is not voluntary, but forced, no longer satisfying in itself, but merely the means for satisfying needs. In other words, rather than the workers creating their own needs, they produce whatever capital needs to make a profit. Therefore, Marx argued, the worker

feels miserable and not happy, does not develop free mental and physical energy… [Work’s] alien character is clearly demonstrated by the fact that as soon as no physical or other compulsion exists it is shunned like the plague.[53]

This alienation from labour, the conscious, creative aspect of humans which marks us off from the animal world, results in the estrangement of one human being from another. This is the real problem with pornography: sex is something alienated from real human relationships. The sex act is portrayed in an alienated, objectified form for a passive, anonymous viewer – as if it is a mirror reflecting the distorted lives of women and men under capitalism.

For Marx, “the whole of human servitude is involved in the relation of the worker to production, and all relations of servitude are nothing but modifications and consequences of this relation”.[54] Put simply, all the oppression and horrors we see around us arise from the basic fact of exploitation of the working class by capital and the particular way that is carried out Because of this alienation, everything is turned into a commodity: the ability to work, everything we need to survive, even leisure and sex (i.e. in the form of pornography, advertising which uses sexual exploitation of women, and prostitution). The feelings of powerlessness workers experience are based on the reality of exploitation and their actual lack of power. This leads them to accept the domination of capital and along with the dominant ideas of capitalism. This then explains why both men and women by and large accept sexist ideas – not some malignant desire by men to dominate women.

Alienation permeates all of life and all classes, though in different ways depending on their degree of social power. To understand its manifestations this philosophical theory must be concretised. Marx’s starting point for understanding society was not “humans in general”:

The premises from which we begin are not arbitrary ones, not dogmas, but real premises from which abstractions can only be made in the imagination. They are the real individuals, their activity and the material conditions of their life, both those which they find already existing and those produced by their activity.[55]

And to understand society, or any aspect of it, we have to understand the totality of all the social relations which make it up. The parts of society cannot be understood abstracted out of that totality, but only as parts of the whole. So to understand women’s oppression and the resulting unequal relationships of women and men in the family, we have to find how they are part of the class society we live in. That is why I began with the way capitalism moulded the family, and how changes in the way production is organised brought changes and contradictions in women’s lives. To say that class is fundamental to an understanding of family violence is not to simplistically “reduce” women’s oppression to class, but to situate that oppression in capitalism, to show how gender oppression intersects with class oppression. They do not just “intersect” as separate aspects of society. Class exploitation gives rise to oppression and so they are fundamentally linked.

The question is frequently posed: why is it that men are the perpetrators of violence rather than women? Marxists and feminists agree the primary reason is because of the unequal relations between the sexes. However, it is worth remembering that most violence is actually carried out by men against other men.[56] Under capitalism, people’s lack of control over their lives makes them frustrated, at times angry, at others passive and apathetic. Anger among workers can lead to trade union organisation and class actions such as strikes. But at an individual level, it can lead to lashing out at fellow workers. The divisions caused by sexism and racism create easy targets for this lashing out. This may mean at times attacking migrant or black workers who can be mistakenly blamed for unemployment, or simply seen as inferior and easy victims. To call the relationship of the attacking worker one of “power” over the migrant or black is to miss the point of the real source of the violence: alienation, or lack of power.

It is easier to see the difference between the actions of the worker and those who possess real power if we look at racism and the ruling class. Ideologues such as Geoffrey Blainey actively campaign to have racist ideas accepted. He actually does have influence: access to journals, the media, etc. At the time of writing, there is a conscious campaign by employers to convince workers that immigrants are the cause of unemployment, not the system of exploitation. Unlike workers, employers and governments have the means to propagate and establish these ideas as the accepted wisdom. The ruling class also gains from their acceptance: workers tum their anger against other workers instead of the government or the bosses. Workers lose from racist attacks, because it is more difficult to unite against their exploiters.

In the family, women are on the receiving end of alienated behaviour. Here, there is a whole ideology which lays the basis for it: women as sex objects, as bound to satisfy their husbands’ every demand, doing the housework and child care as well as working for a wage. When Marxists argue that it is the lack of power which underpins men’s violence to women, this does not deny the unequal relations between women and men, but locates the fundamental reason why individuals bash or rape other human beings in the first place. The oppression of women and the masculine stereotypes explain why it is overwhelmingly men who attack women, not the other way around. However, women do attack those less equal in their homes: their children. I have never found a feminist who will argue this is because of women’s power. To be consistent with the “male power” theories, this would have to be the explanation.

The problem with most research done on these questions is not only that the Marxist concept of class is not understood (often for instance, including white collar workers as middle class, blurring different class positions so that it is impossible to interpret the data in class terms); but also that most research actually sets out to discredit class theories, which affects the clues they look for and the way data is recorded. A survey in which women say their husbands battered them because they did not provide meals on time or refused them sex does not disprove the theory of alienation. No-one, when asked why they drink heavily or indulge in other alienated behaviour will attribute it to “alienation”. If it could be recognised so readily, it would be easy to organise to rid ourselves of the cause of the alienation – capitalist class society!

However, analysing violence against women in class terms does not simply involve dividing society into classes and measuring the level of violence. The working class is not a homogeneous whole – there are all kinds of divisions, some of which (such as religious or ethnic) are often deliberately fostered by the ruling class, or are strengthened as workers look to these identities for solace and support in difficult circumstances. Others arise more directly from divisions in the workplace: white collar workers as a group have different traditions and see themselves differently from wharf labourers or coal miners. These divisions are not set and static. White collar workers identify much more as workers today then a few decades ago. Therefore any study which examined the incidence of violence would have to be sensitive to many varying factors, influences and sometimes rapidly changing situations. Workers involved in high levels of struggle are likely to exhibit less violence. This is often remarked on by participants in mass struggles, especially revolutionary movements. None of these factors is taken seriously in studies which are intent on proving the fundamental division is men against women.

The actions of men who assault women and those of the ruling class, both male and female, shows the difference between alienated behaviour, the result of powerlessness and the use of real power. The media barons actively promote sexist images. They are responsible for helping create the environment where women are attacked. But this is only part of the picture. Employers use the oppression of women quite blatantly to employ them for lower wages in factories with the most appalling conditions and often humiliating practices designed to keep the women in their place.[57] Women in the ruling class employ women as servants for low wages, reinforcing the unequal relations of men and women in the workforce. Prominent middle and upper class women such as Caroline Chisholm last century, Women Who Want to Be Women today, and women who edit women’s magazines for mass circulation, actively promote the sexual stereotypes. At a meatworkers’ picket in Albury in 1991, women played a prominent role trying to stop scabs. Wives of the meat bosses came to the picket and argued to the women workers that their behaviour was unfeminine, and they should not be involved in such disgusting activity. This incident highlights how the feminine stereotype benefits the ruling class. If women can be convinced that class struggle is unfeminine, it weakens workers’ ability to win concessions. On the other hand, the stereotype is not in the interests of working class men, an argument which is often won on picket lines with previously sexist workers. To compare the use of the stereotypes for profit of the ruling class with the violence of men with no social power, oppressed in the workplace and with few options in life is to completely confuse the idea of what social power is, and to let those responsible for the kind of society we live in off the hook. If we merely want to analyse people’s activity as a matter of academic interest, this remains an abstract question. If we want to change the world, it becomes of central importance.

The method adopted by Kirkby and Orr of attempting to distinguish between fundamental cause and less fundamental contributing factors is fair enough. The problem lies in their separation of gender oppression from class relations and their concern that giving any weight to the other contributing factors somehow will downgrade the importance of gender oppression. A Marxist approach is to attempt a concrete analysis in the framework of an understanding that alienation and class exploitation are fundamental. Then we can show how women’s own economic independence (or lack of it), changing (or static) attitudes regarding women’s role come together in the institution of the family.

For all their weaknesses, the most recent books at least focus on women’s experience in the most important institution for understanding women’s oppression – the family. The shift in emphasis from the “stranger danger” stressed by Brownmiller, to the endemic violence towards women in the family is welcome not simply because it more accurately reflects reality, but also because it has encouraged analysis of the family as an institution. For all the weaknesses of a book such as Family Violence, it avoids the sweeping generalisations of earlier feminists such as de Beauvoir and Brownmiller who shared a vision of women as universal victims of male dominance. Their books are immensely influential and back up the widely held view in academic anthropology that women have always been regarded as inferior to men. The most recent books do not explicitly support this idea. Nevertheless, the idea that society is fundamentally divided between men and women is so powerful that without a complete break from it any analysis ends up accepting some version of the idea of “male power”. So it is necessary to establish the serious flaws in the work of writers who propound theories of patriarchy or male power and to show that women have not always been oppressed. This provides a sound basis on which to understand that class society is the fundamental cause of women’s oppression, and the fight for women’s freedom from violence is bound up with the fight for socialism.

Have women always been oppressed?

Marx explained the rise of classes as the result of the production of a sufficient surplus in society to enable a minority to be freed from work and to live off the labour of the majority. Friedrich Engels argued in The Origins of the Family, Private Property and the State that women’s oppression arose with the development of private property and the division of society into classes. In order to keep control over their property and right to exploit, it was necessary for men of the new ruling elite to exert control over women’s reproduction in a way previously unknown. This led to the family where women were subordinated to men. In order to oppress the women of the new elite, all women had to be controlled and regarded as inferior. Engels concluded from this that women’s oppression would only cease with the end of class society. Engels’ theory was grounded in the proposition that the way human society organises production is central to all other aspects of life, that ideas do not come out of the blue, but are products of real material and social circumstances.

Brownmiller and de Beauvoir share a glaring weakness; the enormity of their assertions compared to their research or analytical material. De Beauvoir, in a chapter on the supposed “Data of Biology”, writes about all mammals as though the sexual activity of whales and dolphins can tell us about human society. From this, the male is the superior, aggressive, competitive being, while the female is “first violated…then alienated – she becomes, in part, another than herself” by the fact of a lengthy pregnancy. In an attempt to deny her biological determinism, de Beauvoir appeals to the individualistic theories of existentialism which in turn confirm woman’s “enslavement…to the species”.[58] She accepts the reactionary concept “man the hunter” so common in anthropology and right wing popularised views of human nature: “In times when heavy clubs were brandished and wild beasts held at bay, woman’s physical weakness did constitute a glaring inferiority”.[59] She opposed Engels’ argument:

If the human consciousness had not included the original category of the Other and an original aspiration to dominate the Other, the invention of the bronze tool could not have caused the oppression of woman.[60]

So in spite of her professed attempt to show that women’s position is defined culturally, she repeatedly returns to the concept of a fixed, unchanging human nature, and one which fits with reactionary views of humanity at that. It is not clear why, if this will to dominate is part of original human consciousness, there is any point in discussing women’s oppression – surely it is inevitable.

Brownmiller has been very important in establishing the idea that men have always been violent towards women. It is therefore worth looking at her argument at some length. The striking thing about the book is its complete lack of knowledge of anthropological studies and complete lack of scientific enquiry in support of her sweeping generalisations. How do we know rape is used by all men to intimidate all women? Brownmiller “believes” it.[61] She turns Engels’ idea that women’s oppression arose as a consequence of class divisions on its head:

Concepts of hierarchy, slavery and private property flowed from, and could only be predicated upon the initial subjugation of woman.[62]

What is the evidence for universal violence against women by men? Nothing but unsubstantiated assertions such as:

one of the earliest forms of male bonding must have been the gang rape of one woman by a band of marauding men. This accomplished, rape became not only a male prerogative, but man’s basic weapon of force against women, the principal agent of his will and her fear [emphasis added].

Notice the method: assertions flow from conjecture. Why were the males marauding?

By anatomical fiat – the inescapable construction of their genital organs – the human male was a natural predator.

It was women’s “fear of an open season of rape” which led them to strike the “risky bargain” of “conjugal relationship” and was the “single causative factor in the original subjugation of woman by man”.[63] Since Brownmiller wrote, there has been a wealth of anthropological studies which throw serious doubt on the assertion that women have always been oppressed and therefore have suffered male violence. She cannot be blamed for ignorance of these (although those who continue to propagate her ideas can), however she was not ignorant of evidence which contradicted her statements, and even included it in the book.

For instance, some attempts to understand what the earliest human societies would look like have been based on studies of non-human primates, extrapolating from them to build a picture of human evolution. Brownmiller quotes Jane Goodall, who studied wild chimpanzees and found the female did not accept every male who approached her. Even persistent males were not known to rape. Brownmiller also quotes Leonard Williams’ Man and Monkey which concluded “in monkey society there is no such thing as rape, prostitution, or even passive consent”.[64] Brownmiller claims that because human females are sexually active any time, unlike other primates, men are capable of rape. The implication is that monkeys and chimps are physically incapable of rape. However Sally Slocum found that non-human primates “appear not to attempt coitus (when the female is unreceptive), regardless of physiological ability”.[65] A later study, based on similar observations plus archaeological and anthropological studies, attempted to show how the earliest humans evolved from the animal world into social, tool-using beings:

The picture then is one of bipedal, tool-using, food-sharing, and sociable mothers choosing to copulate with males also possessing these traits.[66]

This might seem an esoteric discussion in an article about violence against women today. However, the idea that men are violent by nature and women passive and nurturing, always an idea of the right wing, is now widely held in feminist circles. So we need to be aware there are two quite distinct strands of feminist thought on the question. The right wing argument was backed up by the anthropological theory that the dawn of humanity was made possible by “man the hunter”. From the mid-sixties there were challenges to this interpretation.[67] New research – much of it, but not all, by feminists – shows that there is the possibility of humans living in harmony and that violence towards women is explained by social and material developments rather than by biology.

The other strand, to which de Beauvoir and Brownmiller contributed, can sound radical because it criticises men’s violence and stereotypes of masculine aggression rather than glorifying them. But let’s be clear, their ideas are just as reactionary as the old “man the hunter” myth because fundamentally they accept the same premise: men are naturally predatory and violent, more capable of dominating than women. Some of Brownmiller’s argument is simply dishonest. She quotes the anthropologist Margaret Mead about a society where rape was unknown: “the Arapesh [do not] have any conception of male nature that might make rape understandable to them”.[68] This clearly raises the concept of rape as a social phenomenon, not simply the result of men’s physiological attributes, apart from the fact that it proves rape has not always been a feature of society. But Brownmiller blithely skips over this inconvenient fact to go on to societies where violence towards women is extreme with no attempt to explain the differences.

When she does attempt an explanation of the absence of rape, Brownmiller is not beyond repeating sexist, elitist attitudes to women’s experiences. Mrs Rowlandson, wife of an ordained minister, was taken captive by American Indians in 1676. On return to white society, she wrote:

I have been in the midst of those roaring lions and savage bears…alone and in company, sleeping all sorts together, and yet no one of them ever offered the least abuse of unchastity to me in word or action. Though some are ready to say I speak it for my own credit, I speak it in the presence of God, and to his glory.[69]

She did well to add the last sentence, but it does not save her from the feminist author three centuries later. Brownmiller admits this story was “not atypical”; she quotes a historian of 1842 who concluded the Indians only learnt to mistreat women by contact with whites. But to admit that Indian men did not rape and abuse women, even those from an invading, pillaging society, would be to admit rape may not be explained by the fact that man discovered at the dawn of time “that his genitalia could serve as a weapon to generate fear”.[70] Instead, she dismisses the evidence by an appeal to the prejudice Mrs Rowlandson foresaw: “the natural reluctance on the part of women to admit that sexual abuse bas occurred”. She does not attempt to explain why women were less reluctant in the later period. She even upholds the old wowserist idea that women do not seek sexual activity, they only have it thrust on them by disgusting males: she dismisses Fanny Kelly’s description of “several braves who went out of their way to do her favours” as an “apparent innocence”.[71]

“Rape in warfare” (says Brownmiller) is not bounded by definitions of which wars are ‘just’ or ‘unjust’.” The examples she gives are the “German Hun” (presumably it is acceptable to be racist about men) in Belgium during World War I, the Russians in World War II, the Pakistani army in Bangladesh in 1971, and the American GIs in Vietnam – none of which could be called a just war from a left wing perspective. The Viet Cong (who were fighting a just, anti-imperialist war), according to news correspondent Peter Arnett and not disputed by Brownmiller, “were prohibited from looting, stealing food or rape… We heard very little of VC rape”. Arnett thought their (extraordinary by his experience) behaviour needed some explanation which he attempted by reference to the fact “they had women fighting as equals among their men”.[72] Brownmiller offers none.

Brownmiller and de Beauvoir could claim credibility because anthropologists until the 1960s almost universally agreed women had always been oppressed. Anthropology, because of its claim to scientific research, was difficult to challenge. However a key starting point for assessing anthropological evidence is a recognition that it is nothing more than collected observations of academics from the more developed world who visited pre-capitalist societies. Their observations cannot be read at face value. Firstly, they took with them the cultural and social views of capitalist society which distorted their interpretation of what they saw. Anthropologists such as Eleanor Burke Leacock, Karen Sacks and others have convincingly shown how male-oriented and prejudiced influential anthropologists such as Malinowsky and Lévi-Strauss were.[73]

Western anthropologists and other observers, imposing their own view of the world on the societies they studied, assumed the nuclear family of modern capitalism to be a universal feature of human organisation of reproduction and sexuality. Society was assumed to be divided into the “public”, male sphere and the “private”, female sphere, a concept clearly associated historically with the rise of capitalism and completely useless in understanding the co-operative, collective nature of gatherer-hunters’ lives. In many societies there was a sexual division of labour in which women took most responsibility for children and gathering, while men did most of the hunting. Because women’s responsibility for child care in our society contributes to their inferior status and oppression, it was erroneously assumed this could be read into the meaning of their work in all societies.[74] Even many feminist anthropologists “assume low status for maternity, which they see as constraining activities, hindering personality development, and reducing women’s symbolic value. They project the values of our culture onto other cultures.”[75] Judith Brown, writing about the division of labour by sex, assumes that women’s reproductive role determines their existence as gatherer-hunters, and that women’s “tasks are relatively monotonous and do not require rapt concentration; and the work is not dangerous, can be performed in spite of interruptions” [by children].[76] This ignores evidence from many societies where women’s work is very skilled and varied, providing the bulk of food. Sacks shows that in some societies, women adapt the number of pregnancies to the needs of production. She showed that !Kung women do not take a break from gathering while nursing their infants, which “attests to the cultural centrality of women’s productive roles, as well as countering a simple minded reproductive determinism”.[77]

Secondly, the eurocentricism of most anthropology obscures the effects of colonial expansion on pre-capitalist societies. As Reiter has noted:

We cannot literally interpret the lives of existing foraging peoples such as the !Kung bushmen of the Kalahari, the Eskimos, the Australian Aborigines – as exhibits and replications of processes we speculate to have occurred in the Paeleolithic. Neither can we assume the decimated, marginalised existences of peoples pushed to the edges of their environment by thousands of years penetration will exhibit original characteristics.[78]

Colonial expansion brought profound changes. These changes can be rapid, affecting research done even at a very early period of settlement. For one thing, members of the society being colonised soon learn strategies for survival and for minimising attacks on themselves.[79] It is widely believed that Aboriginal women were treated as inferior chattels before white settlement. Diane Barwick even went so far as to argue that Aboriginal women gained their emancipation from this oppressive society under the influence of white settlement.[80] All these arguments rest on accounts which reflect the prejudices of early settlers and ignore the catastrophic effects of the white invasion. Henry Reynolds argues:

Most Aborigines used European commodities well before contact and knew at least something about the settlers including the power of their guns and their propensity to use them. Few initial meetings happened in a vacuum. The blacks responded to contact with at least some prior knowledge… We cannot, therefore, assume that what explorers and pioneers observed was necessarily typical of traditional society.[81]

Most accounts of early contact refer to “the natives” as though they were all male. Explorers would have expected to deal with men and viewed women as sex objects if noticed at all. The Aborigines very early on experienced abduction and rape of women by sealers. Reynolds recounts that Torres Strait Islanders told a government official in 1881 that when whites were seen, the women were buried in the sand to avoid ill-treatment.[82] Where this was the case, the male bias of explorers and other observers would have been exaggerated even further. Their impression of gender relations in Aboriginal society would have been of men as the dominant, outgoing sex and women as retiring, submissive and afraid. Once this feature of contact emerged, it had a dynamic which reinforced the exaggeration of the importance of men. The male explorers gave gifts to men. These gifts of tomahawks, knives, flour, sugar, tobacco may seem trivial taken individually. However, as contact increased and the products of white society became more coveted and widespread amongst Aborigines, these gifts could be expected to change the balance of relationships between women and men. For instance, when land was rendered less accessible or productive because of settlement, Aborigines depended more on food from whites. This undercut the women’s ability to provide for themselves and their children independently of the men.

The most common view of marriage amongst the Aborigines is that women were chattels exchanged amongst the men for their benefit where the woman was a slave, cruelly beaten or speared if she showed any infidelity, often denied her share of the food yet performing the most arduous tasks, working all day, minding the children. The fact that marriages were arranged at a very early age or even before birth seems to be proof of the degraded life of Aboriginal women. Anthropologists such as Diane Bell have tackled this question by trying to establish that marriage is not as closely controlled by men as earlier writers suggest. This is most likely true. But there is a more fundamental point. This view of arranged marriages being to the benefit of men reflects a very strong idea of our own culture, that men have an insatiable sexual drive and so are undiscriminating about what woman they have relations with. The fact is, marriages arranged for children mean the male does not have any choice either. If a girl is betrothed before birth, a male cannot know whether she is someone he will want to form a binding relationship with any more than the girl. Because of sexism in our society it is very difficult not to view arranged marriages in the way the nineteenth century settlers did, but once we reject the idea, we can begin to see gender relations in a different light.

Malinowsky, for all his bias, made a relevant point when he wrote that in Aboriginal society it is likely that marriage was not seen as “a question of private initiative and enterprise”, but of “regulated rule, of a well-established order”.[83] The idea of love and romance associated with marriage is a recent concept even in Western society. Even where marriage was associated with ideas of chastity and that sex belonged only in marriage it was the case for centuries that marriage was not seen as individual choice but a social arrangement. In Aboriginal society marriage was not seen as controlling sexuality. Numerous accounts comment on the “promiscuity” of the Aborigines. Bell assembled information from women in Central Australia who could remember the first white men to arrive in the area. She concluded that:

In Aboriginal society, wives were not sold; they were able to exercise a high degree of choice; they fought, they insulted, they remained in their country where their power base was strong. The marriage contract was one between families, it did not entail control over sexuality.[84]

The contradictory and openly biased accounts of gatherer-hunter societies, plus the problem of disentangling the effects of colonialism, sometimes leads to the conclusion that we cannot know what they were like. But the ethnographic record, if researched with these problems in mind, can tell us enough to know that there have been societies where the position of women was as independent participants in egalitarian social arrangements. Leacock has documented the shift from egalitarian social relations to hierarchy and women’s oppression in her studies of the Montagnais-Naskapi of Canada and the Iroquois Indians of North America.[85] She summarised her argument in Current Anthropology:

…the structure of egalitarian society has been misunderstood as a result of the failure to recognize women’s participation in such society as public and autonomous. To conceptualize hunting/gathering bands as loose collections of nuclear families, in which women are bound by dyadic relations of dependency to individual men, projects onto hunter/gatherers the dimensions of our own social structure. Such a concept implies a teleological and unilineal view of social evolution, whereby our society is seen as the full expression of relations that have been present in all society…reinterpretations of women’s roles in hunting/gathering societies reveals that qualitatively different relationships obtained.[86]

It is interesting to read the debate which followed. A constant theme of her opponents is disbelief that there could be an “egalitarian society”, as it is inevitably written. Ronald Cohen dismisses the whole idea of “pre-class” society, “whatever that is” and accuses Leacock of propagating “simplistic”, outdated theories of human development.[87] Instinctively those who want to argue that women have always been oppressed sense they must lampoon any idea that humans may have lived in non-hierarchical, egalitarian societies, because then they cannot explain why women were oppressed.