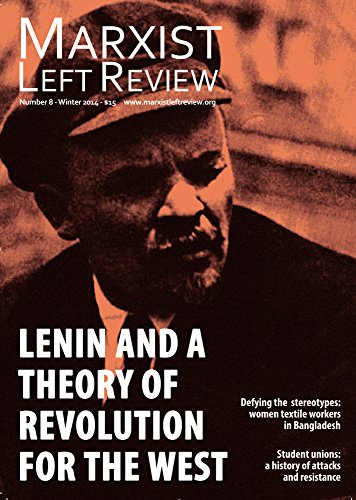

Lenin and a theory of revolution for the West

Playback speed:

“Do not only show the goal, show the path as well

For so closely interwoven with one another are path and goal

That a change in one means a change in the other,

And a different path gives rise to a different goal.”– Ferdinand Lassalle, Franz von Sickingen[1]

“People who pronounce themselves in favour of the method of legislative reform in place of and in contradistinction to the conquest of political power and social revolution, do not really choose a more tranquil, calmer and slower road to the same goal, but a different goal. Instead of taking a stand for the establishment of a new society they take a stand for surface modifications of the old society.”

– Rosa Luxemburg, Reform or Revolution[2]

By October 1917 Lenin had theorised the relationship between the ultimate goal of socialism and the path to it. His experiences of workers’ struggles, from the mass strikes of the late 1890s to the 1905 revolution, and the upsurge of industrial struggles after 1912, had convinced him that:

The real education of the masses can never be separated from their independent political, and especially revolutionary, struggle… Only struggle discloses to [the exploited class] the magnitude of its own power, widens its horizon, enhances its abilities, clarifies its mind, forges its will.[3]

He knew that revolution is not manufactured by revolutionaries; it cannot be brought on at will. The contradictions in the system which cause economic turmoil, war and the like give rise to social crises which create the conditions for revolution. He understood that not all workers came to revolutionary consciousness at once, and that the most advanced – the “vanguard” – needs its own political party. This party must be more than a propaganda machine; it must intervene to take every struggle to the highest level possible. Out of this ongoing class struggle such a party can and must train a membership capable of assessing the political situation, immersing themselves in the working class and leading those around them. He had theorised the state and the role of the soviets as the basis for a new workers’ state, which was the only basis on which the broad masses could begin the task of building socialism.[4]

The tragic defeat of the Russian revolution and the rise of Stalin’s bureaucratic dictatorship were to cast a long shadow. The association of Stalin’s one-party state with Lenin’s liberatory vision – promoted both by Stalin’s acolytes (to give themselves a revolutionary aura) and by the West (where it suited imperialist interests to confront a monstrous state which could be said to be the result of a workers’ revolution) – to this day creates doubt in the minds of many activists who genuinely want to see a better world. The fact that workers in western Europe, in spite of a wave of massive struggles after 1917, failed to carry through successful revolutions has also contributed to confusion and doubt about the possibilities of socialist revolution in the developed democracies.

These doubts and confusions have if anything become more widespread even on the far left, after three decades of the neoliberal offensive by the capitalist class, the failure of the working class to offer a serious challenge to this class war from above and the decline and fragmentation of the left. The terms of debates on the international left over the last few years have moved a significant distance from the conclusions Lenin came to. Lenin’s own writings and interventions into the international socialist movement between 1917 and his tragically early death in January 1924 are a good starting point to defeat those doubts and confusions. In this article I want to show that they can answer the two questions which cast that long shadow over Lenin’s contribution to Marxism: did Lenin lead to Stalin, and can there be a revolution in advanced democracies?

If Lenin was wrong and cannot teach us about socialist revolution, to whom then should we look? It is inconceivable that today, in a time of demoralisation and disarray, a new revolutionary theory can be developed. If one is needed it will have to wait until the next revolutionary challenge by the working class to capitalist rule. Otherwise we would have to assume most of historical materialism is incorrect, that there is no dialectical relationship between theory and practice, and that a theory of how to achieve socialism can be the outcome of good ideas dreamed up in activists’ and writers’ heads, rather than developed in close relationship with the class struggle.

Many of the discussions of Lenin’s ideas and practice give the impression that he was the only one who drew these conclusions. But his theory of revolution was the overwhelming consensus of the Bolsheviks, summarised by Nikolai Bukharin in the program they put to the Third International.[5] The arguments against Lenin which Rosa Luxemburg made from time to time prior to 1917 are cited by some of Lenin’s opponents. If such a great revolutionary disagreed, this must throw doubt on his ideas. But she came to agree with him on the fundamental aspects of his theory of revolution. Figures such as Klara Zetkin, Karl Radek and Leo Jogiches were also in fundamental agreement with Lenin. The arguments made in the Prison Notebooks by Gramsci, a relatively minor figure at the time, have, since the 1970s, been held up as the Marxist debunking of Lenin. The truth is, Gramsci’s writings, both in the Notebooks and his conclusions from the experience of the Biennio Rosso, are in broad agreement with the thrust of Lenin’s theory of revolution. Georg Lukács, inspired by the Russian revolution, for a few brief years developed a philosophical defence of Lenin’s theory and practice.[6] After years of bitter disputes with Lenin, Trotsky, a figure of great standing at the time, became a consistent advocate of Lenin, especially as he struggled to resist the rise of Stalin and to bring about successful revolutions internationally. We have a good chance of keeping alive a genuinely revolutionary understanding of the road to socialism by learning from the heritage they have left us, drawn from the experience of years when workers came closer to overthrowing capitalism in its heartlands than at any other time.

An explanation of the degeneration of the revolution matters very much if we are to understand arguments Lenin made in the last seven years of his life. They can only be understood in the historical context. Any analysis which assumes a seamless line from What Is to Be Done to his arguments to take power in October, and to the rise of Stalin, cannot make sense of his significant theoretical contributions.[7]

Tragically, when the truth which lay behind the iron curtain could no longer be ignored – revealed as it was by tanks rolling into Hungary in 1956 to crush a classic working class revolution which would have thrilled Lenin, then into Czechoslovakia in 1968 to crush the democracy movement – many on the left were riven with doubt about the very idea of workers’ revolution and socialism. The starting point is to understand Lenin in the context of the defeat of the revolution to which he devoted his life. Does the degeneration prove that Lenin’s ideas are irrelevant? I argue it proves him correct in his understanding of the historical conjuncture in which he found himself. Therefore his ideas before October 1917 and then in the Third International must be judged as a contribution to the struggle for socialism by a revolutionary Marxist who, contrary to the cynical portrait so many paint of him, genuinely stood for human freedom. To that end he argued, following Marx and Engels, that goal would only be achieved by workers taking power into their own hands, ideas which permeate his writings to his last letters and article.

Explaining the rise of Stalin[8]

Most conventional academic history provides a linear narrative in which the role of key individuals is usually overstated. Anything that happens was pretty much a foregone conclusion, even if that is only evident in hindsight. And historical events are the result of ideas and intentions in the participants’ heads. On the other hand, much of what passes for Marxist history, especially in academia, paints a picture of events driven by economics or social structures. Neither of these approaches can explain the catastrophe which emerged from the revolution Lenin and the Bolsheviks had led in 1917. On the one hand, it is argued, Lenin’s party implemented the increasingly repressive measures, some of which began while Lenin was alive, which consolidated Stalin’s bureaucratic rule. So Lenin, for all his talk of freedom, must have always envisioned such a state. Alternatively, he was genuine, but either power corrupted him, or the rot at the heart of Bolshevism was revealed. All of these conclusions undermined the idea that socialists should study Lenin’s theory, politics and practice. For the Stalinists, masquerading as the “orthodox” Marxists, the mantle of revolution enabled the Communist Parties in the West to maintain a radical veneer. Their opportunistic (or perhaps in some instances simply misguided) promotion of Stalin’s monstrous state as the desired outcome of Lenin and the Bolsheviks reinforced the anti-Leninist arguments in a suffocating vice of obfuscation. Lars Lih, in his monumental study Lenin Rediscovered, explains in exhaustive detail how the caricature of Lenin’s ideas and the nature of Bolshevism was nurtured on both sides of the East-West divide during the Cold War. Its proponents built on a mythology begun by Lenin’s contemporary opponents.[9]

To understand the degeneration and ultimate defeat of the revolution we need a dialectical understanding of the relationship between social, objective circumstances and subjective intervention by individuals, parties and classes. Trotsky had argued before the 1905 revolution that there could be a socialist revolution in backward Russia. It could not succeed unless the revolution spread to the capitalist centres of western Europe – which was highly probable as any revolutionary crisis in Russia would be mirrored in other important capitalist centres.[10] Lenin never stated that he came to agree with Trotsky’s theory of permanent revolution. However his study of world imperialism after 1914 led him to very similar conclusions. In his April Theses he outlined a program which went well beyond his previous assumption that the revolution would remain within the bounds of a bourgeois democratic revolution. Now he argued that the bourgeois provisional government would not and could not satisfy the demands of the masses, so the workers needed to continue the revolution and take power through the soviets. The fate of the workers’ state would depend on the revolutions in the West which he fully expected to follow because of the generalised crisis caused by the war.

Lenin never hid the fact that he considered that the fate of the revolution depended on workers’ revolutions in the West. In mid-January 1918 he said in an address to the Third All-Russian Congress of Soviets, “[w]e have never cherished the hope that we could finish [the transition from capitalism to socialism] without the aid of the international proletariat.” Returning to this question in the same speech he stated: “The final victory of socialism in a single country is of course impossible.”[11] Trotsky comments in his Permanent Revolution, written as a polemic against Stalin, that no Bolshevik would have dreamed of any other view of their prospects in 1918. The defeat of the revolutions which swept across Europe left the revolution isolated and doomed. Everyone expected that counter-revolution would come in the form of White armies backed by invading imperialist forces, or the overthrow of the soviet government by counter-revolutionary Mensheviks or the Socialist Revolutionaries based on the peasantry. The fact that it was led by an old Bolshevik, using much of the rhetoric of the revolutionary days, albeit distorted and even turned on its head, has been a source of profound confusion ever since.

There are clear indications that Stalin overturned the fundamental principles of the Bolsheviks in order to consolidate his rule, but they are not understood, or at worst, deliberately ignored. For instance, Stalin’s declaration in 1924 that he would build “socialism in one country”. The internationalism of the Marxist tradition was trashed in that one slogan. But the overthrow was not just ideological. In the midst of mass poverty, even mass starvation, and the terrible destruction caused first by war then civil war – with workers displaced from factories by either sabotage by capitalists or shortages caused by imperialist blockade – the population could not assert themselves. During the civil war the soviets ceased to function. How could they? Organs of workers’ and peasants’ self-rule do not exist as the result of sheer willpower or in a vacuum. They can only function on the basis of revolutionary masses engaged in the day to day struggle to defeat their class enemies.

The responsibility for the defeat of the Russian masses lies in part at the feet of Western socialists who had failed to build revolutionary organisations capable of leading the revolutions which promised relief for Russia. Whatever mistakes or unsavoury statements we can find in the written records of Bolshevik activity, whatever repressive measures Lenin was prepared to sanction in order to hold on until the German revolution revived the material basis for workers democracy, none of these are responsible. They are the consequences of a dire situation, of impending defeat. This is clear if we read the record honestly and not in order to “prove” Lenin was always an aspiring dictator because he was for a party and a workers’ state. Trotsky referred in 1937 to a historical fact which should put paid to the idea that Lenin’s Bolshevik party laid the basis for Stalin, the importance of which seems beyond the imagination of most mainstream historians and even Lenin’s critics on the left.

The present purge draws between Bolshevism and Stalinism not simply a bloody line but a whole river of blood. The annihilation of all the older generation of Bolsheviks, an important part of the middle generation which participated in the civil war, and that part of the youth that took up most seriously the Bolshevik traditions, shows not only a political but a thoroughly physical incompatibility between Bolshevism and Stalinism. How can this not be seen?[12]

Lenin after 1917

Those who claim that Lenin began implementing his intended, but previously secret, undemocratic plans as soon as the Bolsheviks formed a government ignore the historical context. To argue that the new soviet government could have moved to build socialism is to accept that socialism in one country, even one as backward as Russia – a reactionary anti-Marxist concept – is possible. It also ignores Lenin’s actual arguments.

Volume 27 of Lenin’s collected works traces his gradual realisation that the Bolsheviks could not implement all the programs they had hoped to. At the extraordinary seventh congress of the party in early March 1918, if Lenin was intent on a one-party dictatorship, determined to repress the masses, you would expect it to be reflected in his address to this internal meeting of comrades. Instead he says: “It was the great creative spirit of the people, which had passed through the bitter experience of 1905 and had been made wise by it, that gave rise to this form of proletarian power.”[13] This point is made in various ways not once, but repeatedly. However he warns against any triumphalist idea that the next steps in the revolution will be as easy as it was to take power in October. He outlines the “fundamental differences” between the bourgeois and proletarian revolutions. The bourgeoisie had gradually built up its economic organisation “in the womb of the old order, gradually changing all the aspects of feudal society.” Their revolution faced just one task, “to destroy all the fetters of the preceding social order.” The socialist revolution not only has to destroy the capitalist order, but also create its own organisation of industry and the economy. In a backward country like Russia, this means raising the cultural level, basic things like accounting, coordinating the economy “in such a way as to enable hundreds of millions of people” to be guided in the project. And the problems are exacerbated by the effects of the war:

[O]nly by the hard and long path of self-discipline [will] it be possible to overcome the disintegration that the war…caused in capitalist society,…only by extraordinarily hard, long and persistent effort [can] we cope with this disintegration and defeat those elements aggravating it.[14]

The second issue which confronted the workers’ state was “the need to solve the international problems, the need to evoke a world revolution, to effect the transition from our strictly national revolution to the world revolution. This problem confronts us in all its incredible difficulty.”[15] He repeats several times this basic point: “There would doubtlessly be no hope of the ultimate victory of our revolution if it were to remain alone… I repeat, our salvation from all these difficulties is an all-European revolution.”[16] Never, from now until his death, does Lenin hold out the promise of building socialism in Russia alone. He returns to this absolute necessity for the German revolution to rescue them another two or three times in the same address. But it was not an argument to give in to counter-revolution: “This does not in the least shake our conviction that we must be able to bear the most difficult position without blustering.”[17]

His theme, in defending the Brest-Litovsk agreement signed with Germany and violently opposed by the Left Communists, is to face reality, to recognise the dangers, to avoid adventures like trying to fight a war with a disintegrating army. “If the European revolution is late in coming, gravest defeats await us because we have no army, because we lack organisation, because, at the moment, these are two problems we cannot solve. If you are unable to adapt yourself, if you are not inclined to crawl on your belly in the mud, you are not a revolutionary but a chatterbox; and I propose this, not because I like it, but because we have no other road, because history has not been kind enough to bring the revolution to maturity everywhere simultaneously.” And finally, “[w]e should have but one slogan – to learn the art of war properly and put the railways in order… We must produce order and we must produce all the energy and all the strength that will produce the best that is in the revolution.”[18]

In those words we get a glimpse of the contradiction which Lenin would face: the need for order out of chaos and destruction, while maximising the energy of the masses he always relied on to make the revolution, when they were starving, facing mass unemployment and without the means to rebuild industry.

At the end of March Lenin refers to “the extremely critical and even desperate situation the country is in as regards ensuring at least the mere possibility of existence for the majority of the population, as regards safeguarding it from famine – these economic conditions urgently demand the achievement of definite practical results.” The countryside could possibly feed itself, he says, but only if a distribution system of “the greatest economy and carefulness” is put in place, “with millions of people working with the precision of clockwork”.[19] Lenin had emphasised what he saw as the core of proletarian democracy, first seen in the Paris Commune and then in the soviets: decision-making and execution of those decisions are united, unlike in bourgeois society where their separation is seen as admirable. Now, with the desperate attempts to keep production going, he begins to talk about having individuals in positions of authority, weakening the core of soviet democracy. But every time he mentions this, Lenin accompanies it with statements like this one:

[N]aturally, the aspect characterised by discussion and the airing of questions at meetings prevails over the business aspect. It could not be otherwise, for without drawing in the new sections of the people into socialist construction…there could be no question of any revolutionary change. The endless discussions and endless holding of meetings – about which the bourgeois press talks so much and so acrimoniously – is a necessary transition of the masses…from historical somnolence to new historical creativeness.[20]

In the same article he returns to this question: “The masses must have to choose responsible leaders for themselves. They must have the right to put forward any worker without exception for administrative functions.”[21]

Both Neil Harding and Lars Lih, two of the most astute and honest biographers of Lenin, trace the ambivalence of many of Lenin’s formulations from now on. Both chart something of a disintegration of his usually sharp, coherent thinking. And both understand it in the context of the reality he faced.[22] This is a critical point. Because there is contradiction, ambivalence, unresolvable problems, those with an ideological agenda can find any number of quotes which paint Lenin as an unrelenting authoritarian. Policies which served emergency purposes in order to survive until the revolutions in Europe brought help became entrenched because the rescue never came. And gradually, during the late 1920s, they became associated with the Stalinist bureaucracy. It is too simplistic to draw a straight line from the beginning to that end point. As Harding points out:

[P]olicy proposals and organisational suggestions [made in the desperate situation in 1918 when feeding the population looked almost impossible] were to characterise the entire subsequent attitude of the Bolsheviks towards the economy. Many commentators assume that they had always been part and parcel of Lenin’s “organisational scheme”; they had not. They were radical revisions of his initial project and incompatible with it however desperately Lenin sometimes sought to square the circle and make them appear as one.[23]

Gradually Lenin more clearly admitted the measures his government was implementing were not steps towards socialism, but in fact a retreat. Writing about the employment of bourgeois specialists at high salaries, he spells it out:

Clearly this measure is a compromise, a departure from the principles of the Paris Commune and of every proletarian power, which call for the reduction of all salaries to the level of the wages of the average worker, which urge that careerism be fought not merely in words, but in deeds…it is also a step backward… To conceal from the people the fact that [this is a retreat from socialist principles] would be sinking to the level of bourgeois politicians and deceiving the people.[24]

His words are not those of someone who either relishes being at the top of a bureaucracy or who is indifferent to this threat. At the end he states that the more the government has to resort to using individuals to organise production, “the more varied must be the forms and methods of control from below in order to counteract every shadow of a possibility of distorting the principles of Soviet government, in order repeatedly and tirelessly to weed out bureaucracy.” And he concludes:

[A]n extraordinarily difficult, complex and dangerous situation in international affairs; the necessity of manoeuvring and retreating; a period of waiting for new outbreaks of the revolution which is maturing in the West at a painfully slow pace; within the country a period of slow construction and ruthless “tightening up”… Try to compare with the ordinary everyday concept “revolutionary” the slogans that follow from the specific conditions of the present stage, namely, manoeuvre, retreat, wait, build slowly, ruthlessly tighten up, rigorously discipline, smash laxity… Is it surprising that when certain “revolutionaries” hear this they are seized with noble indignation.[25]

At a meeting with the most active workers in Moscow at the end of April 1918, in a report on the immediate tasks of the soviet government, Lenin explicitly informs them that they are really in a holding operation, depending on the German revolution: “Our task, since we are alone, is to maintain the revolution, to preserve for it at least a certain bastion of socialism, however weak and moderately sized, until the revolution matures in other countries.”[26] In his address to the July 1918 All-Russian Congress of the Soviets, he grasps at any news that workers are learning how to better administer the economy and takes every opportunity to urge his audience to keep pushing workers into positions of responsibility. Speaking of resources put towards organising food for the cities, he argues: “Much still remains to be arranged, and you can do it if you only have the desire. But through whom, I do not know. Not through the old officials, surely? Our workers and peasants on the Soviets are learning to do it (applause).” His address ends on a hopeful note. Steps are being taken to deal with profiteers, workers are learning from their mistakes and understand the gravity of the situation. Fair trade with the poor peasants is beginning to be organised, exchanging discounted textiles for bread. The poor must be the first to benefit. Always he makes an assessment of the involvement and advances of the masses: “We have made tremendous strides in the education of the peasants, and they are now no longer novices in the struggle for socialism.”[27]

Lenin sounds less harried, whether because he is trying to imbue his audience with the strength to go on, or because he feels they have made important steps forward. But within weeks the counter-revolution, which until then had been confined to scattered acts of terror and sabotage, became a serious threat. In a communication of 20 July to Bolsheviks in Petrograd, he urges them to send thousands of workers to Moscow or the government will perish under attack from the Czech troops threatening the city. A week later he sends word that 60,000 troops in the Kuban are advancing to join up with the Czechs and contingents of British troops and Cossacks. If Petrograd does not send thousands of workers, the Bolshevik leaders “will make themselves responsible for the downfall of our whole cause.”[28] The civil war had now advanced from a political contest to all-out military conflict. “Holding on” took on a whole new meaning that would continue until his death because of the failure of the revolutions in western Europe. In 1923, in one of his last articles, he combines optimism that the revolution will be victorious with a recognition that, as Lars Lih puts it:

All socialist Russia had to do was hold out (proderzhat’sia) until the final victory. In this article of five printed pages Lenin not only uses “hold out” twice, but also employs words with related meanings and based on the same root (derzhat’) for a total of six more times.[29]

The horrors of the civil war are well known. Victor Serge, a libertarian with an eye for the authoritarianism he abhorred, follows the process during 1918 whereby the hopes of October were curbed and modified. He makes it quite clear this was not Lenin’s program, but the necessary response to imperialist and counter-revolutionary threats beginning days after the Petrograd seizure of power. His account of the Left Communists in the Bolsheviks, now named the Russian Communist Party, makes it clear it was not just the “authoritarian” Lenin who rejected their program. At the Seventh Congress of the RCP at the end of February 1918, they moved a resolution which stated “It would be in accordance with the interests of the world revolution, we believe, to accept the sacrifice of Soviet power, which is becoming purely formal.”[30] This in itself clarifies the stark choice the workers’ state faced: accept counter-revolution or hold out. Serge supports Lenin’s reply, in which he said this statement was “strange and monstrous”, “truly dishonourable”.

Far from improving the chances of the German revolution, he pointed out commonsensically, the sacrifice of Soviet power would do it considerable harm. Did not the workers of Britain become cowed by the defeat of the Commune in 1871?[31]

Serge’s own summary of the Lefts’ position closely parallels Lenin’s critique of them, even using terms like “childish” which Lenin had imputed to their ideas. If there had been a libertarian alternative, Serge would have embraced it enthusiastically, but he did not:

The Left Communists’ case was founded…upon deeply rooted feelings: indignation, sorrow, anger and a tragic pessimism on the future of the revolution, all the more tragic in that it was mingled with an almost blind enthusiasm which involved a desire for total sacrifice…expressed in a number of surprising declarations: “If the Russian revolution…does not flinch, no one can master it or break it”… How was the country to hold on in reality? A “mobilisation of spirit” was needed… Here a very perceptive idea was mixed up with a very misleading utopianism…it was childish to argue that German technique could be opposed with socialist convictions.[32]

In reply to a comrade who advocated full freedom of speech in 1921, Lenin’s words reflect the extreme situation they faced. This would not just mean freedom of speech, but freedom for the bourgeoisie to organise politically, which would mean “making the enemy’s job easier and helping the class enemy”. This enemy had the support of the encircling imperialists, the Mensheviks and other powerful forces. “We do not wish to do away with ourselves by suicide.”[33]

The Bolsheviks had a choice: leave the masses to the brutality of the Whites, which by then was well known, or continue to defend the revolution in the hope of revolution in the West. Serge and others have documented the creeping bureaucratisation of the RCP which resulted from this defensive situation. As one of the few who witnessed this degeneration and remained a supporter of the revolution, Serge is clear. In a chapter on “war communism”, he links the increasing centralisation to the civil war.

The party’s old democratic customs give way to a more authoritarian centralisation. This is necessitated by the demands of the struggle and by the influx of new members who have neither a Marxist training nor the personal quality of the pre-1917 militants; the “old guard” of Bolshevism is justly determined to preserve its own political hegemony.[34]

Those who charge Lenin with responsibility for the repressive state apparatus which Stalin was to build conjure up an image of his ruthless thirst for power and his authoritarian agenda. They either explicitly or implicitly create the impression that there was a peaceful, democratic alternative available to him. But as he argued from 1917 until 1924, the fate of the Russian revolution rested entirely on revolution in the West. There would be no socialism only within the borders of Russia. But we can agree with him and the rest of the Bolshevik leadership – and the millions who mobilised for three years to drive out the imperialists and to defeat the Whites – that they were right to fight in order to hold on. They could not predict that the revolutions which swept Europe after November 1918 – when German sailors mutinied and workers’ and soldiers’ soviets were created in Germany – would all fail.

In spite of the unimaginable suffering of millions as they defended their hope for a new society against everything the capitalist world could throw at them, the arguments Lenin and other Bolsheviks made during those terrible years do not represent the core ideas of Marxism or of Lenin. They are the expression of that holding-on operation. We can leave the last word on this tragic situation to Rosa Luxemburg, who is often misleadingly invoked as an opponent of Lenin:

The awkward position that the Bolsheviks are in today, however, is together with most of their mistakes, a consequence of the basic insolubility of the problem posed to them by the international, above all the German, proletariat. To carry out the dictatorship of the proletariat and the socialist revolution in a single country surrounded by reactionary imperialist rule…that is squaring the circle. Any socialist party would have to fail in this task and perish… The blame for the Bolsheviks’ failures is borne in the final analysis by the international proletariat and above all by the unprecedented and persistent baseness of German Social Democracy.[35]

The relevance of Lenin’s theory of revolution

At the same time as dealing with civil war, chaos, famine and assassination attempts, Lenin put considerable effort into establishing the Third International, for which he had been agitating ever since the collapse of the Second International in 1914. Now it was the logical political conclusion from his conviction that the victory of revolutions in the West were the only way out for Russia. The first letter of invitation went out days after Luxemburg and Liebknecht had been murdered in Berlin. The German revolution made the possibility of a genuine International a reality. The attempts to guide the revolutionaries who had before the war been inside mass parties with a rhetorical commitment to Marxism, but reformist in practice, provide us with a rich source of revolutionary theory which remains relevant today. This is not the place for a history of the Third International; one journal article could not do justice to the wealth of knowledge which exists.[36]

Many of the debates in the International’s congresses concerned tactical issues such as how to implement a united front, what attitude to take to “left” or “workers’ governments”. And these have been the subject of much debate. How useful are the debates and decisions in the Congresses of the Third International as a guide to what revolutionaries should do today? John Riddell, who has done the most to record the history of the early years of the Third International, makes a valid point in one of the most recent exchanges:

Lenin’s Comintern is no infallible guide to socialist program and strategy in the twenty-first century. That said, we must guard against the impulse to turn our backs on its achievements. The early Comintern is strong on many issues where today’s Marxism is weak; it engages with issues that today’s Marxism often evades; even its errors, often overlooked, are instructive.[37]

In order to judge these debates and take from them what is useful today we need a compass. What is the goal? If you don’t support workers’ councils taking power, then you will have a very different assessment of the value of the Comintern debates from someone who does. How do we define socialism? Is it human liberation, or a more humane version of capitalism? How can it be achieved? Here I want to outline the theory of revolution which Lenin articulated and with which the other great revolutionaries of the time grappled, and test the relevance of their conclusions for this century in light of arguments being made on the international left today.

In October 1919 Lenin gave a definition of socialism: “the abolition of classes”. And he went on to spell out the idea central to his thinking: “The dictatorship [of the proletariat] will only become unnecessary when classes disappear. Without the dictatorship of the proletariat they will not disappear.”[38]

Arguments against this position which have gained popularity with some on the international left today are put forward as new, innovative, and in tune with the modern world. But they read like nothing more than reworked versions of ideas first promoted in the years 1918-1923 by Karl Kautsky and others in the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD). Murray Smith, one of the most prolific English language promoters of these ideas, also assumes that the advanced economies differ so radically from Russia that the experience of 1917 is tantamount to irrelevant. He declares: “There has never been a socialist revolution in an advanced capitalist country with a more or less long tradition of bourgeois democracy. Never, nowhere”, as a justification for his argument that the struggle for socialism will not inevitably involve insurrection in which workers’ organisations take power.[39]

But Lenin, Trotsky, other Bolshevik leaders openly talked about the difference between Russia and western Europe in the debates in the Comintern. In 1919 Lenin wrote: “I have had occasion more than once to say that it was easier for the Russians than for the advanced countries to begin the great proletarian revolution, but that it will be more difficult for them…to carry it to final victory, in the sense of the complete organisation of a socialist society.”[40] What Smith should have said is that there has not been a successful revolution in the advanced countries. France in 1936 and again in 1968, Italy in 1969-1970 for instance raised the possibility. However, I think his criterion is too restrictive. How many countries were both advanced economically and had a long tradition of bourgeois democracy until well after World War II? This criterion leaves us with very little historical experience on which to draw. Was Chile in 1972-1973 “advanced”? It certainly had a tradition of bourgeois democracy. Germany might not come up to his definition of having a tradition of democracy, but Kautsky and others drew a sharp distinction between it and Russia to justify their position in opposition to the Bolsheviks. The revolutionary upheavals in Ireland at the end of World War I occurred under a long-established bourgeois democracy. Was Italy in 1919-1920 advanced? Bordiga argued that it was qualitatively different from Russia to justify his ultra-leftism. Spain in the 1930s was a democracy, but not advanced. The experience of all these failed revolutions provides vital lessons for any theory of revolution in the advanced countries today – as long as we can take account of the differences with each country’s experience.

Lenin quickly began to draw conclusions from the German revolution.

Until it had been put to the test, it was still impossible to say what changes, of what depth and importance, the development of the world revolution would bring. The German revolution has provided that test. An advanced capitalist country, coming after one of the most backward, has demonstrated to the whole world in a matter of a hundred-odd days not only the same principal revolutionary forces and principal direction of the revolution, but also the same principal form of the new, proletarian democracy – the Soviets.[41]

And in his arguments with revolutionaries in the West he regularly refers to the experience of Russia, drawing out the lessons from the 1917 revolutions which have general relevance. In “The Third International and its Place in History”, written in April 1919, he points to the uneven nature of developments, which is to be expected. Not all revolutions will develop along the same lines or at the same pace. Revolutionaries have to develop the ability to judge both national and international developments and respond correctly. But it is clear that the fundamentals do not change: the struggle for workers’ power and no illusions in bourgeois democracy.[42] So it tells us nothing to assert, as does Murray Smith, that socialist“strategy and tactics…will have to be developed in the course of the struggle and they will be very different from Russia in 1917.”[43] This is the self-evident conclusion of Lenin’s theory of revolution. Lenin’s reply to Bordiga in Left Wing Communism, an Infantile Disorder, written in April-May 1920, is also the answer to Smith:

[T]he unity of the international tactics of the communist working class movement in all countries demands, not the elimination of variety or the suppression of national distinctions…but an application of the fundamental principles of communism (Soviet power and the dictatorship of the proletariat). The overthrow of the bourgeoisie; the establishment of a Soviet republic and proletarian dictatorship – such is the basic historical task [in the advanced countries].[44]

Lenin’s argument just as easily applies across time as it does to geographical space as long as capitalism remains the mode of production.

In Russia, the dictatorship of the proletariat must inevitably differ in certain particulars from what it would be in the advanced countries, owing to the very great backwardness and petty-bourgeois character of our country. But the basic forces – and the basic forms of social economy – are the same in Russia as in any capitalist country, so that the peculiarities can apply only to what is of lesser importance.[45]

Lenin, Trotsky, Gramsci and Luxemburg, drawing on the experience of revolutions in the advanced European countries, concluded that parliamentary democracy was the mode of capitalist rule, a bourgeois dictatorship. And the soviets, or the “conciliar system” as it was called in Germany, represented the foundation on which a new society could be built. These two systems represent rule by different classes and so they cannot coexist indefinitely.

Lenin’s theory of revolution

To understand Lenin’s arguments after 1917 and his debates about revolution in the developed democracies, it’s useful to sum up the different elements of Lenin’s theory and practice which, when taken together, constitute a coherent theory of revolution.

The arguments for soviets, workers’ power, revolution and insurrection rest on a fundamental thesis first put forward by Marx and Engels in The German Ideology. In order to establish socialism, they argued, “the alteration of people on a mass scale is necessary, an alteration which can only take place in a practical movement, a revolution; the revolution is necessary, therefore, not only because the ruling class cannot be overthrown in any other way, but also because the class overthrowing it can only in a revolution succeed in ridding itself of all the muck of ages and become fitted to found society anew”.[46]

There is an assertion by a section of the left today that mass disillusionment with the old reformist parties means the distinction between reform and revolution is no longer relevant. This is to seriously misunderstand the material roots of reformist ideas. For one thing, reformism is only one specific version of bourgeois ideology. The influence of these ideas does not rely on mass reformist parties alone. In any case, even where unions have been seriously weakened, the trade union bureaucracy still has influence capable of keeping alive reformist illusions, or at least keeping a lid on spontaneous outbursts of struggle. The response to the devastating austerity programs of the European ruling classes is a graphic reminder of this influence.

A theory of revolution needs to be grounded in an understanding of the influence of bourgeois ideology, because a transition to a society of freedom has to involve destroying its influence. Why do workers accept ideas which justify their own exploitation, which naturalise oppression and keep their rulers in power? Lenin did not explicitly articulate a theory about this question. However his practice flowed from the Marxist theory of consciousness. In Capital Marx discusses how the market and the commodities sold on it, while created by humans, dominate our lives and obscure how society works. The feeling of powerlessness this breeds means workers defer to authority figures and therefore are prone to accept ideas propagated by them. Lukács called two dialectically related processes – commodity fetishism and alienation – reification.

There is both an objective and a subjective side to this phenomenon. Objectively a world of objects and relations between things springs into being (the world of commodities and their movements on the market). The laws governing these objects…confront [us] as invisible forces that generate their own power… Subjectively…a worker’s activity becomes estranged from himself, it turns into a commodity which, subject to the non-human objectivity of the natural laws of society, must go its own way independently of people just like any consumer article.[47]

Workers therefore tend to accept bourgeois ideas, including reformism, not because they are stupid or uneducated. It’s not that they’re just duped by the media or reformist parties, but because of very real, material circumstances inherent in the structure of the capitalist economy. Any explanation of how workers can become class conscious and the subject of history must, then, look to the structures of capitalism. The contradictions inherent in the system, the ceaseless “revolutionising of the means of production”, create recurring crises which have the potential to bring workers into ever sharper confrontation with their employers and the capitalist state. These crises reveal that there is nothing “normal” about the rule of the market and raise the possibility of revolution. Lenin was always clear that revolutionaries do not make revolutions, they need to be organised and prepared to lead the masses when they enter revolutionary struggle. Once workers break the chains of passivity and acceptance, as Marx famously concluded in the Theses on Feuerbach, workers change themselves.

The materialist doctrine that men are products of circumstances and upbringing, and that, therefore, changed men are products of changed circumstances and changed upbringing, forgets that it is men who change circumstances and that the educator must himself be educated. Hence this doctrine is bound to divide society into two parts, one of which is superior to society. The coincidence of the changing of circumstances and of human activity or self-change [Selbstveränderung] can be conceived and rationally understood only as revolutionising practice.[48]

Mass struggles, by ripping away the veil of mysticism which surrounds our lives, by breaking apart the sense of powerlessness which crushes workers into subservience, raise the possibility of revolutionary consciousness.

As early as 1895, Lenin had concluded that workers learnt most from struggle. In a draft program for the social democrats he drew out this point: “The mass of working folk learn from [the] struggle, firstly, how to recognise and to examine one by one the methods of capitalist exploitation… By examining the different forms and cases of exploitation, the workers learn to understand the significance and the essence of exploitation as a whole, learn to understand the social system.” And in the process of struggle they “learn to understand the need for and the significance of organisation.” As the struggle widens, it “develops the workers’ political consciousness.”[49] This would be a theme in Lenin’s writings until his death. In 1915, addressing students in Zurich, he said: “Only struggle educates the exploited class. Only struggle discloses to it the magnitude of its own power, widens its horizon, enhances its abilities, clarifies its mind, forges the will.”[50] This is the answer to the problem of bourgeois ideas such as reformism. In her book The Mass Strike, Rosa Luxemburg celebrated the spiritual and cultural development of the workers in the strikes which swept the Russian empire in 1905.

In his Prison Notebooks Gramsci outlined an aspect of consciousness which is an important addition to Marx, Lenin and Lukács. It takes account of the fact that workers enter the struggle with mainly reformist ideas.

The active person-in-the-mass has a practical activity, but has no clear theoretical consciousness of their practical activity… Their theoretical consciousness can indeed be historically in opposition to their activity. One might almost say they have two theoretical consciousness (or one contradictory consciousness); one which is implicit in their activity and which in reality unites them with all their fellow-workers in the practical transformation of the real world; and one, superficially explicit or verbal, which they have inherited from the past and uncritically absorbed. But this verbal conception is not without consequences. It holds together a specific social group, influences moral conduct and the direction of will, with varying efficacy but often powerfully enough to produce a situation in which the contradictory state of consciousness does not permit of any action, any decision or any choice, and produces a condition of moral and political passivity. Critical understanding of self takes place therefore through a struggle of political “hegemonies” and of opposing directions.[51]

This also strengthens the argument for a revolutionary (vanguard) party, so that the most advanced workers can play a vital role in that struggle between different currents of thought in the workers’ movement.

Genuine class consciousness is more than just understanding that this is a class society. Gramsci’s definition of class consciousness was the “precise consciousness” of a class of “its own historical identity”.[52] Workers need to understand that as a class they are capable of running a new society and that they can defeat their present rulers. In practice, Lenin saw genuine class consciousness in these terms (although he used the term loosely all the time). For instance, in 1917, some of his most urgent agitation was for the Bolsheviks to imbue workers with a sense of their own ability to run society, not to trust the government, that they had to take power through their own organisations. As Gramsci puts it: “The unity of theory and practice is not just a matter of mechanical fact, but a part of the historical process.” A feeling of independence can mature and progress “to the level of real possession of a single and coherent conception of the world.”[53]

From late 1917 and during 1918 Lenin repeatedly returns to the concept of socialist consciousness – as opposed to a class consciousness, which is learned by industrial struggle, and political consciousness developed by taking up political issues and dealing with the violent reactions of the ruling class to workers’ struggles. Workers could only develop socialist consciousness by the struggle to defend the workers’ state, learning to administer the tasks of the state and organise the economy, thereby developing a confidence in their own creativity and ability to run society. “Creative activity at the grass roots is the basic factor of the new public life… Socialism cannot be decreed from above. Its spirit rejects the mechanical bureaucratic approach; living, creative socialism is the product of the masses themselves.”[54] Neil Harding sums up Lenin’s thinking on this issue well when he points out that for Lenin, workers’ involvement in running society themselves and dealing with ruling class parasites and saboteurs was “the means to attain the goal and the goal itself.[55]

Murray Smith dismisses “a strategy based on seizing state power from the outside” in which case “you seize power through insurrection and build a new state power”, because we know from Russia that it “was not so easy”. So by implication, his strategy which is “based on a conquest of power through universal suffrage and therefore occupation of the state” would be easy. He admits we don’t know if it can be done, but “the hypothesis would be that a government would come to power, would begin taking measures in the interest of those who had elected it, begin to make inroads into capitalist power and property, and also begin to transform the state. It would certainly encounter resistance from within the state and from without, from within the country and without, and would need to mobilise its social base.”[56] Ed Rooksby, in an ongoing debate in the publications of the British Socialist Workers Party, echoes Smith’s and others’ arguments. The road to socialism will be mass mobilisations to force a “left” or “workers” government to implement so-called “revolutionary reforms”. In Smith’s hypothesis, “forms of popular self-organisation based on workplaces and neighbourhoods would appear, not in a confrontation with the state but in support of their government, even with some inevitable elements of friction”.[57]

Not to take power, not to take control into their own hands, just to support a parliamentary government. See how this jars when compared with how revolutionaries who thought self-emancipation was the only basis for socialism spoke of the working masses involved in actual revolutions. Smith and Rooksby give no explanation of how the mass of workers, let alone the masses from the middle classes who surround them, would develop the consciousness to make them capable of transforming society. Gramsci’s attack on those who lack confidence in workers to take control comes to mind: “They see the workers as the material instruments of social transformation rather than as the conscious and intelligent protagonist of revolution.”[58]

Winning proletarian hegemony

Lenin spells out how the class struggle continues after the revolution; that while weakened, the bourgeoisie in Russia is far from defeated. And the working class has to continue to attempt to lead the petty bourgeois masses, to “give leadership to the vacillating and unstable [social elements]”. Gramsci would later theorise this as winning “hegemony”. This ongoing struggle, argues Lenin, shows “how unutterably nonsensical and theoretically stupid is the common petty-bourgeois idea shared by all representatives of the Second International, that the transition to socialism is possible ‘by means of democracy’ in general. The fundamental source of this error lies in the prejudice inherited from the bourgeoisie that ‘democracy’ is something absolute and above classes.”[59] We should note here that Lenin is not just talking about Russia. He is making a general point about the nature of the struggle for socialism; it must involve first the overthrow of the ruling class, and second the establishment of working class hegemony and power.

For all the fetishisation of the concept of hegemony in discussions of Gramsci, it is most often misrepresented. Distorted accounts of his position are employed to legitimise the argument that the key struggle for socialists is not a direct assault on state power, but the struggle for ideological hegemony over civil society. This is a long drawn out process, a “war of position” which in practice leads to limiting potentially revolutionary class struggle as premature. Actually, Gramsci argues in the Prison Notebooks that the totality of civil society and the state apparatus forms an “integral state” which ensures the continuing hegemony of the ruling class. “In actual reality civil society and State are one and the same.” And he argues that, confronted with this integral state, the working class must fight for ideological dominance over other social layers which can potentially be allies. Ultimately it will need mass forces which can impose its domination over its enemies by a revolutionary seizure of power. And, like Lenin, Gramsci thought workers would win this hegemony in the class struggle, not simply by propaganda. Even when the war of position plays a predominant part, Gramsci speaks of a “partial” element of the war of manoeuvre. It may play a “more tactical than strategic function.”[60] At any time there can be an outburst of struggle, initiated by either side in which their relative strengths are tested; or perhaps one side may inflict something of a defeat on the other, changing the place they occupy in the trenches of the war of position.

Lenin and Gramsci – for all the attempts to use Gramsci’s writings to insist there is little to be learnt from Lenin – had essentially the same fundamental theory of revolution. There is nothing to suggest Lenin would have disagreed with Gramsci when he wrote that “the supremacy of a social group manifests itself in two ways, as ‘domination’ and as ‘intellectual and moral leadership’.”[61] In his summary of the history of the Bolsheviks in Left Wing Communism, Lenin’s account of preparation for revolution, the period of reaction after 1907 and the years of the war is dominated by ideological clarification and the struggle to defeat non-revolutionary theories. Even the months between February and October in 1917 were spent making arguments to the mass of workers to win them away from the influence of the Mensheviks and others.[62]

These years of propaganda and theoretical work prepared for revolution. Lenin’s discussion of the sharp reorientation any revolutionary party must make when revolution is on the agenda does not contradict Gramsci, but in fact confirms the similarity in their positions: “[W]hen it is the question of practical action by the masses, of the disposition, if one may so put it, of vast armies, of the alignment of all the class forces…for the final and decisive battle, then propagandist methods alone…are of no avail… In these circumstances one must count in tens of millions. In these circumstances we must ask ourselves…whether the historically effective forces of all classes…are arrayed in such a way that the decisive battle is at hand.” For that, the mass of the proletariat must see the bankruptcy of the ideas of the petty bourgeoisie and the necessity for determined revolutionary action must have “emerged and grown vigorously”.[63]

Gramsci’s writings about civil society have encouraged the idea that the main struggle is against the church, the education system, the media. The ideas propagated by them do have to be combated. But once workers move into struggle the biggest danger comes from reformist and centrist ideas propagated by those who are supposed to be on their side. They feed that lack of confidence rooted in the very structures of capitalism and create hesitations which open up the opportunity for the bourgeoisie to unleash counter revolution. After a year of failed revolutions in western Europe, Lenin was acutely aware of this. Just one typical passage will suffice as illustration.

One of the necessary conditions for preparing the proletariat for its victory is a long, stubborn and ruthless struggle against opportunism, reformism, social-chauvinism, and similar bourgeois influences and trends, which are inevitable, since the proletariat is operating in a capitalist environment. If there is no such struggle, if opportunism in the working-class movement is not utterly defeated beforehand, there can be no dictatorship of the proletariat.[64]

Dictatorship of the proletariat

Lenin had by then polemicised bitterly and relentlessly against Kautsky and the USPD. In an article “The proletarian revolution and the renegade Kautsky”, published in Pravda on 11 October, 1918, he had begun to clarify “a question of the utmost importance, the question of the relation between the dictatorship of the proletariat and ‘democracy’.” Because “it is here that Kautsky’s complete break with Marxism is particularly evident.”[65] In his better known pamphlet The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky, Lenin emphasised that “the dictatorship of the proletariat…is a question that is of the greatest importance for all countries, especially for the advanced ones… One may say without fear of exaggeration that this is the key problem of the entire proletarian class struggle.”[66]

In popular discourse, it is not generally appropriate to talk of dictatorship of the proletariat. But for the purposes of a serious discussion of the question of revolution and workers’ power it remains a clarifying concept. Lenin returns to this question repeatedly, raising issues which remain relevant today. The crux of Lenin’s attack on Kautsky is that he misrepresents the Marxist understanding of the state because “he takes every opportunity to energetically preach ‘the democratic instead of the dictatorial method’.” This counterposition “is a complete renunciation of the proletarian revolution, which is replaced by the liberal theory of ‘winning a majority’ and ‘utilising democracy’!” Kautsky has rejected the need for workers “to ‘smash’ the bourgeois state machine.” He “has renounced Marxism by forgetting that every state is a machine for the suppression of one class by another, and that the most democratic bourgeois republic is a machine for the oppression of the proletariat by the bourgeoisie.”[67]

Smith and Rooksby do not explain what a reforming government and mass mobilisations could do to avoid the inevitable state violence and political mobilisation by the capitalist class. Smith predicts that “[i]n the best of cases, the two elements, the government and the mass movement would mutually reinforce each other.”[68] Typically, Smith asserts this as a possible scenario, but cannot point to one “left” or “workers” government which even supported and encouraged revolutionary mobilisations by workers, let alone any which tried to carry through the transition to socialism. Every such government has played a key role in defusing the mass movement and ensuring the preservation of capitalist rule. The German reformists and centrists of the SPD and USPD formed a government in 1918. They used their positions as politicians to sow confusion by blurring the distinction between bourgeois and proletarian democracy. They participated in the process of building armed militias which became the basis for the Frei Korps which marched around Germany crushing strike movements, uprisings and protests. Four and a half years later, in 1923, a so-called “workers’ government” was formed in Saxony. Brandler, a key Communist Party (KPD) leader, against his better judgement, entered this coalition with the SPD. When troops were moved in to crush it, the SPD threatened to walk out if Brandler called for a general strike, paralysing the revolutionaries. The twentieth century was plagued by similar betrayals. The Popular Front government in Spain in 1936, which refused to arm the working class in response to Franco’s military uprising; in France in 1936 the Popular Front government moved to defuse the mass upheaval which brought it to power; Allende’s Popular Unity government in Chile in 1973, backed up by the Communist Party, took generals into the cabinet as they prepared their coup.

In Hungary and Bavaria in 1919, bourgeois power virtually collapsed and “workers’ governments” formed. The main participants in these governments were revolutionaries. In Bavaria, the revolutionary Leviné argued that the government must arm the working class and begin the process of establishing workers’ councils based in the workplaces as the basis for genuine workers’ power. Anything short of this, he argued, would end in counter-revolution. He rightly refused to join the government with centrists and reformists who he knew would refuse to carry out these tasks. In the event both revolutions were crushed because the revolutionaries failed to establish workers’ states. Leviné’s position was similar to the one Lenin had adopted in the final months of 1917. The Kerensky government, even if it only included the workers’ parties, had to be replaced by soviet rule. The most Lenin would countenance was to be a loyal opposition if and as long as the government began implementing major demands of the masses. In any case, history shows that revolution may or may not be sparked by the election of a “workers” government, but it is not by any means the general rule. The German revolution of 1918 to 1923 began with sailors’ mutinies and the creation of workers’ and soldiers’ councils. Italy’s Biennio Rosso of 1919-1920 and again the Revolution in Slow Motion of 1969-1970 were both the result of factory occupations and mass strikes. In France 1968 student rebellions sparked mass strikes which put revolution on the agenda.

Formulations by Smith and others imply that if the movement just keeps inching forward with “revolutionary reforms”, the capitalists will be driven back, even if they are “hostile”. They seem to assume the masses provide some orderly army which will act at the behest of an elected government. Or, even more unrealistically, that the government will respond positively to initiatives by the masses. This ignores the actual history of the crises, ruptures, partial victories and setbacks which are inevitable in any revolutionary process as capitalists respond and reformists intervene. All the historical evidence shows that governments and mass movements did not just reinforce each other in revolutionary situations. And the nature and role of bourgeois democracy and parliament as compared with workers’ own institutions of democracy has become a vital question. The example of Germany will suffice as illustration. An account of any of the revolutionary situations I have mentioned would serve, not in any way to contradict, but to reinforce the point.

In Germany, Luxemburg and the Spartacists struggled to form the KPD in the midst of the first revolutionary upsurge at the end of 1918. Then they floundered when workers mobilised in January 1919. Luxemburg correctly opposed calls for insurrection as premature; but, unlike Lenin in July 1917, she lacked an organisation with roots among the masses which could have given her the authority to help minimise the offensive and lead workers in an orderly retreat. Luxemburg, Liebknecht, Jogiches and others paid with their lives, leaving an inexperienced party to deal with tumultuous events. In March 1920, right wing generals sent General Kapp to Berlin to bring down the SPD government. It had only been tolerated to prevent a Communist takeover; now the SPD had served its purpose. The KPD faltered. It opposed calls for strikes and so was sidelined by a massive response by the working class, missing an opportunity to strike a decisive blow against the old regime. Then in March 1921, a newly confident KPD with a mass membership lurched into an ultra-left adventure. They urged workers to arm for an insurrection. Untrained in the politics of the united front, they declared “who is not with us is against us”.

Tragically, non-communist workers did not respond, giving the SPD and its bourgeois backers the evidence they needed to paint the KPD as divisive wreckers, creating the atmosphere for full-blown counter revolution. In the growing crisis of 1923, the KPD leadership, lacking confidence to take the lead and call on workers to go on the offensive and prepare for an uprising, let a revolutionary situation gradually dissipate. Brandler’s participation in the government built illusions among workers that the government would solve the crisis for them, breeding passivity just when they needed to advance. The KPD could not even defend the government, let alone revive the possibility of insurrection, sealing the fate of the revolution.

Lenin’s arguments cut through the ideology surrounding bourgeois democracy which permeated the centrist USPD and which has echoes in the arguments raised by Smith and others today, on several levels. Kautsky presented the question as “the contrast between two socialist trends”, that is, Bolshevik and non-Bolshevik, which “is the contrast between two radically different methods: the dictatorial and the democratic”. Kautsky accuses the Bolsheviks of “opportunely” taking up one “little word” (dictatorship) used by Marx as justification for their undemocratic methods. Lenin’s outrage at this “substitution of eclecticism and sophistry for dialectics” is palpable. The degree to which Marxism had been misinterpreted and misrepresented in the Second International went well beyond the despicable sell-out of 1914. Now Kautsky was denying the need for proletarian revolution and the suppression of the capitalist exploiters. Lenin’s detailed refutation of every aspect of Kautsky’s fudging and misstatement of the issues is fascinating reading, his anger permeates his polemic. He revisits the experience of the Paris Commune and the conclusions Marx and Engels drew from it – which he had rediscovered when he returned to Marx and Engels after 1914 and spelt out in his pamphlet The State and Revolution.[69]

Lenin does not fudge the fact that workers need to crush their bourgeois exploiters. He had summed up the key questions in the earlier, shorter piece in Pravda. All states exist for the suppression of one class by another. It is not possible to “have liberty, equality and so on where there is suppression. That is why Engels said: ‘So long as the proletariat still needs the state, it does not need it in the interests of freedom but in order to hold down its adversaries, and as soon as it becomes possible to speak of freedom the state as such ceases to exist.’ Bourgeois democracy…is always narrow, hypocritical, spurious and false; it always remains democracy for the rich and a swindle for the poor. Proletarian democracy suppresses the exploiters, the bourgeoisie – and is therefore not hypocritical, does not promise them freedom and democracy – and gives the working people genuine democracy.”

The examples he gives of what Russian workers did to ensure their democracy are easily imagined in a modern democracy. Things such as taking mansions away from the bourgeoisie (today, instead of palaces, it could be huge convention centres and hotels), without which freedom of assembly is sheer hypocrisy; taking the print-shops and stocks of paper away from the capitalists, without which freedom of the press for workers “is a lie”; and replacing the bourgeois parliament with the “democratic organisations of the Soviets, which are a thousand times nearer to the people and more democratic”.[70]

In the Pravda article he demands that Kautsky “admit that the Soviet form of organisation is of world-wide, and not only of Russian significance, that it is one of the ‘most important phenomena of our times’ and that it promises to acquire ‘decisive significance’ [Kautsky’s words] in the future ‘battles between capital and labour’.” Kautsky’s position “that the Soviets are all right as ‘battle organisations’, but not as ‘state organisations’ is a capitulation to Menshevism”, the followers of which had at the time mostly joined the counter-revolution in Russia. Lenin’s sarcasm gives a sense of how much he despised this kind of fudge by centrists trying to maintain some credibility as Marxists while abandoning Marxism’s central propositions in practice.

Marvellous! Form up in Soviets, you proletarians and poor peasants! But for God’s sake, don’t you dare win! Don’t even think of winning! The moment you win and vanquish the bourgeoisie, that will be the end of you: for you must not be “state” organisations in a proletarian state. In fact, as soon as you have won you must break up!.. Workers of Europe, don’t think of revolution until you have found a bourgeoisie who will not hire [political and military reactionaries] to wage civil war on you![71]

Lenin was determined to convince the revolutionaries in the West that Kautsky’s arguments did not represent a more democratic road to socialism, were not a more moderate interpretation of Marxism, but a complete break from Marxism and a betrayal of the fight for socialism. This was a theme of his intervention into the First Congress of the Third International in March 1919. By then he had the concrete experience of the failed German revolution and the murder of two of Europe’s greatest revolutionaries in the debacle. If anything was to be rescued for the world’s workers, the argument for the workers’ councils to take power had to be won. In the “Theses on Bourgeois Democracy”, he wrote that those who present the issues as “non-class or above-class”, in other words, those who do not distinguish between bourgeois and proletarian democracy but speak of “democracy in general” or “dictatorship in general”, have joined the ranks of the bourgeoisie.[72]

Pierre Broué’s wonderful book on the German revolution draws out very clearly how the arguments of Kautsky and the centrist USPD disoriented revolutionary militants in Germany.[73] For all the reasons outlined by Daniel Lopez in this issue, the naturalisation of bourgeois rule means it is imperative that revolutionaries can provide a clear theoretical and political alternative for workers finding their way to power. Such an alternative rests on a rigorous adherence to a class view, explaining issues from the different viewpoints of the exploiters and the exploited. So Lenin contrasts the Marxist and liberal views of democracy. The Marxist view is that the state, including a democracy, serves the interests of the exploiters “as long as there are exploiters who rule the majority”. Therefore the democratic state is an instrument of their rule. The liberal says “the majority decides, the minority submits. Those who do not submit are punished. That is all. Nothing need be said about the class character of the state…because it is irrelevant.”[74] As Laine pointed out in one of his questions, Smith sounds more like Kautsky than Marx. Just like Kautsky, he gives lip service to mass mobilisations, even attributing a role to popular councils while using the very classless terminology Lenin critiqued: “If the Left is not capable of winning majority support how is it going to carry out its programme and confront the forces of reaction?” And the popular – note not workers’ – councils would exist “not in a confrontation with the state but in support of their government”, as if the government is separate from the state.[75]

Soviets

A critique of bourgeois democracy and the alternative posed by workers’ revolution invites a discussion of soviets, or workers’ councils.

Kautsky argued that the soviets played a positive role as combat organisations which embraced the whole of the working masses. Indeed the soviet “promises to acquire decisive importance in the great decisive battles between capital and labour.” What that decisive role would be is immediately obscured by his argument that the Bolsheviks, only after the October revolution, “set out to transform the Soviets…into a state organisation”. Lenin makes three arguments against this. First, Kautsky has not noticed that at least since his April Theses Lenin had argued that the soviets needed to take power. Secondly, as a matter of theory, it is not coherent to approve of the soviets as instruments of class struggle but then oppose them taking power. How else can the working class end the rule of capital and begin the process of defeating the forces which rally to the old ruling class, while building a socialist society? Thirdly, at the level of practical politics, it was clear in the Paris Commune and in Russia that “such an organisation, of its own accord, with the development of the struggle, by the simple ‘logic’ of attack and defence, comes inevitably to pose the question point blank.” The Mensheviks, whose arguments Kautsky is mimicking, in fact tried, by exercising their influence, to use the soviets to subordinate the working class to the bourgeoisie.[76]

Lenin was developing his ideas about the soviets well before 1917. After the 1905 revolution, he had outlined the important role the soviets play in drawing the vast mass of the population behind the working class. The soviets create a forum in which the masses can participate in debates and discussions about the struggle. They can, and indeed should, include non-proletarian forces, to involve them in the revolutionary process.[77] They are the most profound form of democracy yet seen. Delegates are recallable at any time, a fact shown by the shifts in Menshevik, Socialist Revolutionary and Bolshevik influence during 1917. The Bolsheviks lost some of their influence after the July Days. But after their leading role in the struggle against the Kornilov coup in August, their numbers began to rise relentlessly, giving them a majority in those which held elections by early September. No bourgeois parliament can reflect rapidly developing class consciousness like that. So the soviets are at once forums for political debate by the masses and a vehicle for mass involvement in the political process; they express the political opinion of the masses. And, in the final showdown between exploiters and oppressed they provide the structures by which the working class and its supporters can be involved in first destroying, or “smashing” (the word Lenin repeatedly used, following Marx and Engels) the existing state machinery, and then learning to run society themselves.

In early March 1917, in the first of his Letters from Afar, Lenin described the Soviet of Workers’ Deputies as “the embryo of a workers’ government, the representative of the interests of the entire mass of the poor…i.e., of nine-tenths of the population, which is striving for peace, bread and freedom”.[78] Luxemburg is appropriated as an opponent of Lenin’s arguments because she criticised the Bolsheviks for abolishing the Constituent Assembly in January 1918. But a year later, she agreed with the Bolsheviks when she took on the arguments of Kautsky in the context of the actual revolution. She wrote:

The choice today is not between democracy and dictatorship. The question which history has placed on the agenda is: bourgeois democracy or socialist democracy… The dictatorship of the proletariat…means using every means of political power to construct socialism, to expropriate the capitalist class… A class organisation is needed to sharpen [the conscious will of workers], to organise this activity: the parliament of the proletarians of town and country.[79]

Like Lenin, Trotsky and Luxemburg, Gramsci came to see the importance of workers’ councils through his experience. In the occupation of the Turin factories in November 1920 he saw that they could not just be improvised when revolutionaries decided. They are born as an organ of workers’ struggles in the workplaces. He wrote: “The problem of the development of the internal commissions…came to be seen as the fundamental problem of the workers’ revolution; it was the problem of proletarian ‘liberty’.”[80] And Lukács, in accord with all the great revolutionaries of the time, wrote one of the best summaries of the importance of soviets:

As organisations of the entire proletariat (both conscious and unconscious) the workers’ councils by their mere existence point the way forward beyond bourgeois society. They are by their very nature revolutionary and organisational expressions of the growing significance, the ability to act and the power of the proletariat.

As such they are the true index of the progress of the revolution. For everything that is achieved and attained in the workers’ councils is wrested from the defiant grasp of the bourgeoisie, and is therefore valuable not simply as a result, but chiefly as a means of education for class-conscious action.

Attempts to “anchor the workers’ council in the constitution”, to assign them a legally established field of activity, therefore indicate a new peak in “parliamentary cretinism”. Legality is the death of the workers’ council…